Leiden University Centre for Digital Humanities

Archived

PhD Research Projects:

Sign Language Corpora

Outline of the Sign Language Project

Aims of the Project

Exploring new methods in comparing Sign Language corpora: Analysing cross-linguistic variation in the lexicon.

1. Develop new tools for facilitating the compilation and harmonization of a cross-linguistic ID gloss database for sign languages of deaf communities (henceforth: SLs).

2. Explore the application of methods designed for measuring and modelling variation in spoken languages onto SL corpus data.

Leiden Sign Language Corpora

Between 2007 and 2014, four large video corpora (www.africansignlanguages.org/downloads/) of West African SLs have been compiled at Leiden University, under guidance of the applicant. From 2007 to 2012, two large projects took place to document local SL use at various places in Mali and Ghana leading to three digital video corpora. The first Malian Sign Language corpus contains recordings of SL use by deaf signers in Bamako and Mopti, consisting of over 27 hours of recorded discourse, featuring 65 signers (Nyst 2008; 2010). The second Malian Sign Language corpus contains the results of a SL survey in the Dogon area of Mali, notably in Bandiagara, Douentza and surrounding villages and Berbey, close to Hombori. This corpus contains 32 hours of signing of 68 signers and includes signed conversations, interviews and lexical items in at least three independent SL varieties (Nyst, Sylla, Magassouba, forthcoming). The third SL corpus contains a set of discourse data of around 30 hours and 15 signers of Adamorobe Sign Language, which emerged spontaneously in response to the high incidence of hereditary deafness in the village of Adamorobe, Ghana. In 2014, the fourth extensively annotated corpus was archived, containing a representative sample (around 30 hours of 9 signers) of the emerging SL of the village of Bouakako in Côte d’Ivoire. All corpora are glossed in ELAN (Crasborn & Sloetjes 2008). All corpora are glossed in French, except the Adamorobe Sign Language corpus, which is glossed in English and Akan. Lexical databases with phonological coding are available for all corpora, except the second Malian SL corpus. All corpora are stored either at the Endangered Language Archive in London or the DoBeS archive in Nijmegen, or both.

Challenges

Comparison of these corpora would open a unique window on the type, distribution and degree of lexical variation found within and across SLs. Analysis of cross-linguistic variation of SL lexica as documented in corpora is crucial for historical-comparative studies of SLs as well as for understanding contemporary patterns of variation. Indeed, our understanding of how SLs cluster in language families is still mainly based on historical information and urgently needs to be informed by language-internal evidence. The West African SLs in the corpora provide a rather unique opportunity for studying how related and unrelated SLs compare lexically. Whereas most SLs studied so far have been used by communities that have been in contact with each other and are either related or have a shared history of contact. The set of corpora include various village SLs that have evolved in communities with a high incidence of hereditary deafness. The absence of a shared history between these village SLs enables us to contrast variation between related and unrelated SLs, not influenced by contact. Over the past decade, corpus projects documenting SLs have started in various countries. The cross-linguistic comparison of these corpora is complicated for various reasons, one of them being the lack of a shared orthography for SLs. Instead of using an annotation system with components representing the main formal components of a sign, ID glosses are typically used. These consist of a uniquely identifying spoken language word (written in capitals) that by definition refers to a particular sign form, e.g. the ID gloss ENTER for the sign in figure 1. ENTER in fact has multiple meanings, including ‘go in’ or ‘put in’.

Currently, measuring variation across corpora is complicated by the non-compatibility of the glosses used. ID gloss databases are set up separately for each SL corpus. The glosses draw from different spoken languages and that there is no one-to-one relation between glosses and the meaning(s) of the signs. New methods for measuring variation in and across SL corpora need to be explored.

Innovation

To enable cross-linguistic comparison of SL corpus data, new methods and tools need to be developed. A project in which a PhD student in Data Science collaborates with the PI and a deaf research assistant would be ideal for this purpose. The set of Leiden SL corpora can be used for the purpose of developing and testing the tools and methods explored in this project.

PhD Project

1. Set up a database with shared ID glosses. The project will probably use SignBank for the purpose of storing and managing a unified set of ID glosses for the four corpora (Cormier et al. 2012). This format that is gaining in popularity and is currently used for Australian SL, British SL, Dutch SL.

2. Automated entry generation & phonological coding. Ensuring a consistent use of ID glosses is extremely labour intensive, but a condition for reliable quantitative analyses of SL corpora. To achieve this consistency, a lexical database is needed to keep track of signs, their variants, and their ID glosses. Each entry consists of a video clip, a gloss, and phonological coding of the form of the sign. Partial automatization of this process will reduce the exorbitant time investment required for the creation of ID gloss repertoires. Various components of the process may be automatized, including automated entry generation and automated generation of suggestions of matching candidate glosses. A promising improvement that will be explored is the automated phonological coding on the basis of sign input captured with a 3D camera (such as Microsoft ® Kinect). Kinect can automatically detect the position and orientation of 25 joints (including the thumb) as well as facial expressions and a small number of studies have experimented the use of this device for automated SL recognition (Halim & Abbas 2015).

3. Automated analysis & visualization of variation Once a (pilot) set of glosses have been harmonized across the corpora, various tools for measuring and modelling variation will be explored. This will include testing the usefulness and applicability of GabMap, an online tool for measuring and mapping dialectal and other variation in spoken languages (Nerbonne et al 2011).

Relevance

The area of SL corpus linguistics is rapidly growing. The outcomes of this project will open up new possibilities for analysing variation in and across these corpora. The tools and methods explored and developed in the proposed project will provide a major step forward in the historical-comparative analysis of SLs – an area where the field of SL linguistics is strikingly lagging behind as compared to the field of spoken language linguistics.

Ideally, the results of this research project will be made accessible to the research community by creating userfriendly tools that make assessing variation and/or historical-comparative analyses of SLs accessible to the SL linguistics community. An important output consists of a tool that will facilitate the compilation of a database of ID glosses for SLs for which no collection of ID glosses exists prior to the compilation of a discourse corpus. Another tool will consist of an add-on that allows SL researchers to apply user-friendly tools developed for measuring spoken language variation (like GabMap) on SL data.

Workplan & Supervision

Year 1

- acquire a basic knowledge of SL structure (phonology, morphology, and lexical semantics).

- familiarize with ELAN (software used for annotation of the Leiden SL corpora).

- inventory the possibilities and limitations of lexical databases, including SignBank, used with SL corpora.

- Write paper I: identifying challenges and opportunities for applying new methods and tools to lexical databases of SLs.

Year 2

- Design software (lexical ontology/relational database) for the storage and management of standardized glosses across the corpora (Standardized Glosses Tool).

- Test the tool with a representative group of users.

- Improve the Standardized Glosses Tool on the basis of feedback of the test group.

- Write paper II on the development of the Standardized Glosses Tool and the feedback study.

Year 3

- Explore the possibilities for automated entry generation plus automated phonological encoding in the Standardized Glosses Tool with a Kinect sensor.

- If time allows, explore the possibilities for automated entry generation on the basis of still images and video clips

- Design and test tools for automated entry generation

- Write paper III on automated entry generation for lexical databases.

Year 4

- Write paper IV on automated phonological encoding.

- Explore the possibilities of using an existing, user-friendly tool for the automated analysis & visualization of variation (e.g. GabMap [Nerbonne et al. 2011]) on the data in the Standardized Glosses Tool.

- Write paper IV on analysing and visualizing geographic and other variation in lexical signs in and across SLs.

- Merge papers into a PhD thesis.

The student will meet his/her supervisor biweekly to discuss the progress. The student will be encouraged to spend a semester abroad to learn new skills and enlarge his/her network. The results of this project will be regularly reported in during scientific meetings, including the SL workshops of the LREC conferences (www.lrec-conf.org/), and the largest SL conference TISLR (www.slls.eu/tislr-conferences/).

References

Cormier, K., Fenlon, J., Johnston, T., Rentelis, R., Schembri, A., Rowley, K., ... & Woll, B. (2012, May). From corpus to lexical database to online dictionary: Issues in annotation of the BSL Corpus and the development of BSL SignBank. In 5th Workshop on the Representation of Sign Languages: Interactions between Corpus and Lexicon [workshop part of 8th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, Turkey, Istanbul LREC 2012. Paris: ELRA. pp. 7–12.

Crasborn, O., Sloetjes, H. (2008). Enhanced ELAN functionality for sign language corpora. In: Proceedings of LREC 2008, Sixth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation.

Halim, Z., & Abbas, G. (2015). A Kinect-based sign language hand gesture recognition system for hearing-and speech-impaired: a pilot study of Pakistani sign language. Assistive Technology, 27(1), 34-43.

Nerbonne, J., Colen, R., Gooskens, C., Kleiweg, P., & Leinonen, T. (2011). Gabmap-a web application for dialectology. Dialectologia: revista electrònica, 65-89.

Nyst V., Magassouba M.M. & Sylla K. (2011) Un Corpus de Reference de la Langues des Signes Malienne I. A digital, annotated video corpus of the local sign language used in Bamako and Mopti, Mali. Leiden University Centre for Linguistics, Universiteit Leiden.

Nyst V., Magassouba M.M. & Sylla K. (2012) Un Corpus de reference de la Langue des Signes Malienne II. A digital, annotated video corpus of local sign language use in the Dogon area of Mali. Leiden University Centre for Linguistics, Universiteit Leiden.

Nyst V. (2012) A Reference Corpus of Adamorobe Sign Language. A digital, annotated video corpus of the sign language used in the village of Adamorobe, Ghana. Leiden University Centre for Linguistics, Universiteit Leiden.

Tano, A. (2014) Un corpus de référence de la Langue des Signes de Bouakako (LaSiBo). Leiden University Centre for Linguistics, Universiteit Leiden.

DeSDA Detecting Cross-Linguistic Syntactic Differences Automatically

Outline of the DeSDA Project

The goal of this project is to investigate the possibility of automatic detection of syntactic differences between languages by using on-line parallel corpora and software tools for annotation, search and analysis. This approach has the potential to greatly enhance the empirical basis of theoretical comparative syntax research and will enable syntacticians to do theoretical modeling of syntactic variation based on quantitative analysis of the correlations between syntactic properties. Since the project should be seen as a test case for this larger goal and has to be carried out by one PhD student, the research topic will be narrowed down to the (morpho-)syntax of verbs in Germanic languages, including auxiliaries. The main descriptive question will be: Which differences do we find in the Germanic languages with respect to the structural positions of verbs and with respect to verbal inflection? The main theoretical question will be: To which extent is the existing theory of verb placement and inflection as it has been developed since the late eighties of the 20th century capable of capturing these facts? Background Comparative syntax is the branch of linguistics that describes cross-linguistic syntactic similarities and differences and tries to capture them in a formal theory that explains range, limits and loci (i.e. place within the mental grammar) of syntactic variation in natural language [1]. It seeks to answer the question which syntactic properties are universal, which are language specific and how these properties interact. Traditionally, syntacticians collect data by comparing their native languages with other languages, by consulting reference grammars and linguistic colleagues (e.g., Taalportaal for Dutch and Frisian [2]; the typological database WALS [3]), by carrying out surveys and fieldwork (cf. [4]) and by expert sourcing (e.g., SSWL [5]). These methods have in common that the researcher needs to have expectations, in the best case a theory, of the kind of syntactic differences to be found. Consequently, many differences will not be detected, descriptions will be incomplete and correlations between syntactic differences will often not be discovered.

Moreover, the number of (morpho-)syntactic differences between two languages or language varieties is potentially very high, even if these varieties are closely related. E.g., the Syntactic Atlas of the Dutch dialects ([6], [7]] describes more than 100 syntactic differences between closely related and superficially very similar Dutch dialects. Since the number of language varieties to be included in the comparison is also very large (a conservative estimation would be 6000 languages times the number of dialects that each of these languages has), it will be clear that these traditional methods of collecting comparative data are very slow and incomplete and that there is a need for corpora and tools that make automatic, systematic and rigorous qualitative and quantitative syntactic comparison possible.

Corpora and Tools

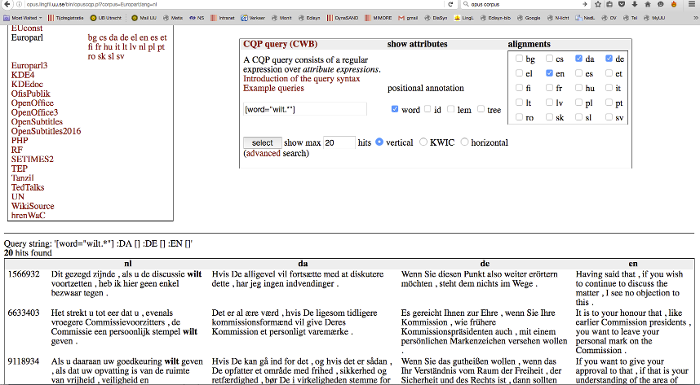

The Opus corpus [8] seems to be the answer to this need. It contains large parallel corpora such as Europarl (parallel texts from the European Union) and OpenSubtitles 2016, among many others. According to Tiedemann [9], in 2012 the Opus corpus covered over 90 languages, 3,800 language pairs with sentence-aligned data comprising a total of over 40 billion tokens in 2.7 billion parallel units (= aligned sentences and sentence fragments). Various interfaces are available to search these corpora. In figure 1 we see the output of a multilingual corpus query in Opus, a set of aligned sentences.

The human observer can immediately derive syntactic differences from this result. For example, we see in the second fragment that wilt geven in Dutch corresponds to vil give in Danish, versehen wollen in German and want to give in English, with differences in the inflection of the verbs, the presence of (an equivalent of) to, the position of the two verbs within the clause (e.g., clause final in Dutch but clause initial in Danish) and the relative order of the two verbs (e.g., wilt geven in Dutch but versehen wollen in German).

Tasks and Questions

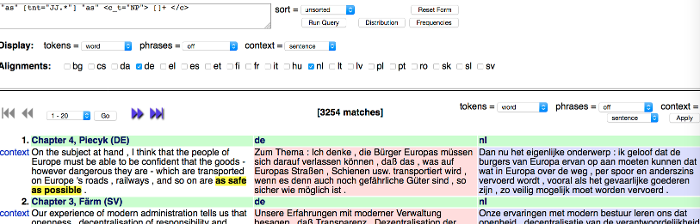

To make automatic extraction of syntactic differences possible, alignment is required also at the level of words (ideally, morphemes), POS-tags and phrases (subtrees). This in turn requires that POS-taggers and parsers are available for each of the languages in the comparison. The OPUS website provides links to language specific POS-taggers and parsers for Czech, Chinese, Danish, Dutch, English, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Portugese, Russian, Slovene, Spanish, Swedish and Turkish [10]. Syntactic comparison will be possible if the same tagset can be used for each of the languages involved (cf. [11]). A probably more feasible alternative is to define mappings between tag sets, using relations such as ‘identical’, ‘near identical’, ‘subsumes’ etc. A first task of the PhD student is to make uniform or mapped tagging and parsing possible for the Germanic languages involved, in the ideal case also at the morphosyntactic level. A second task is to deal with the errors resulting from automatic tagging and parsing (cf. [12]). A third task is to develop automatic alignment at the level of morphemes, words, tags and subtrees. A fourth task is to develop a tool to select only those fragments for which syntactic comparison is possible. There will be many pairs of sentences for which syntactic comparison will be impossible, not because the syntax of the two languages is too different but because the syntax of the two sentences is too different. E.g., in the search result in figure 2 the English phrase On the subject at hand corresponds to German Zum Thema and Dutch Dan nu het eigenlijke onderwerp. If for Dutch the translation Over dit onderwerp had been chosen, the three phrases could have been compared, but now the translation is “too free” syntactically. The tool that filters out such cases will have to work with a threshold for syntactic correspondences, using Levenshtein distance and other techniques to measure syntactic similarity [13].

When alignment is provided at these levels, automatic extraction of syntactic differences becomes possible. A good example of an extraction method is described in Wiersma et al. [14]. They compare the varieties of English spoken by two different cohorts of Finnish immigrants in Australia with a method that contains the following steps: POS tag the text corpora to be compared, take n-grams (1-5 grams) of POS tags from it, compare their relative frequencies using a permutation test, sort the significant POS-n-grams by extent of difference, analyse the results. This method provides the results at an aggregate level and identifies the n-grams of POS tags that are primarily responsible for the syntactic differences between the two language varieties. Tools for this method are available [15]. It needs to be investigated whether the method of Wiersma et al. can also be applied in the comparison of language varieties that are less closely related than the English varieties of Finnish immigrants. This will be the fifth task. If feasible, it can be extended to the comparison of parse trees (cf. [16]). The differences thus detected at the various levels of alignment will be stored in a database. The sixth task involves quantitative analysis. Once a list of syntactic differences between the languages under comparison is derived, associations between syntactic variables can be detected with data mining techniques (cf. [13]). The seventh and final task is then to evaluate these associations in the light of current theories of verbal syntax. Although there are many open issues, since Pollock’s seminal paper [17] there is a rough consensus that cross-linguistically at least three structural positions are available where verbs occur, depending on their morphology: A clause final V-position corresponding to the base position of the verb (both finite and non-finite), a clause medial T-position where tensed and inflected verbs occur, and a clause initial C-position where finite verbs go to mark the clause type. In addition, verb placement and inflection has been relatively well described and analyzed for the Germanic languages (cf. [18], [19]) so that both the descriptive and the theoretical results can be evaluated.

Research Program and Supervision Scheme (1)

Year 1

• Adaptation/uniformization/mapping POS-taggers and parsers and error correction.

• Developing a tool for alignment of parallel texts at the level of morphemes, words, POS-tags and subtrees.

Deliverables: Tools, paper, talk.

Supervision: Barbiers/Odijk.

Year 2

• Developing a tool for the selection of syntactically comparable fragments.

• Testing automatic extraction of syntactic differences using the method of Wiersma et al.

Deliverables: Tool, database of syntactic differences, paper, talk.

Supervision: Barbiers/Odijk

Year 3

• Optimizing the tools.

• Data mining to discover syntactic associations.

• Integration of data and tools in CLARIAH

Deliverables: Paper, talk.

Supervision: Barbiers/Odijk

Year 4

• Evaluation of the results, i.e. the syntactic differences and associations found, against existing descriptions and analyses.

• Writing the thesis.

Deliverables: Dissertation.

Supervision: Barbiers/Odijk.

References

[1] Cinque G. and R. Kayne eds. 2008. The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Syntax. New York: OUP

[2] www.taalportaal.org.

[3] www.wals.info

[4] www.dialectsyntax.org

[5] sswl.railsplayground.net/

[6]/[7] Barbiers, S., et al. 2005/8. Syntactic Atlas of the Dutch Dialects. Volumes I and II. Amsterdam: AUP.

[8] opus.lingfil.uu.se/

[9] Tiedemann, J. 2012, Parallel Data, Tools and Interfaces in OPUS. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2012).

[10] cf.//opus.lingfil.uu.se/trac/wiki/Tagging%20and%20Parsing

[11] Cf. http: // universaldependencies.org /

[12] Bloem, J. 2016. Evaluating automatically annotated treebanks for linguistic research. In Piotr Banski et al. (eds.) Proceedings of the 4thWorkshop on Challenges in the Management of Large Corpora (CMLC 4), 8 – 14, Paris. ELRA.

[13] Spruit, M. R. 2008. Quantitative perspectives on syntactic variation in Dutch. Diss. U. of Amsterdam. LOT Dissertations 174.

[14] Wiersma, W., Nerbonne, J., and T. Lauttamus, 2011. Automatically Extracting Typical Syntactic Differences from Corpora. Literary and Linguistic Computing 26(1).

[15] en.logilogi.org/Wybo_Wiersma/User/Com_Lin_Too.

[16] Sanders, N. C. 2007. Measuring Syntactic Differences in British English. In Proc. of the Student Research Workshop, 1 – 7. Omnipress, Madison.

[17] Pollock, J-Y. (1989). Verb Movement, Universal Grammar, and the Structure of IP. Linguistic Inquiry 20, 365-424

[18] Platzack, C. and A. Holmberg, 2008. The Scandinavian Languages. In G. Cinque and R. Kayne (eds). The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Syntax. New York: Oxford University Press.

[19] Zwart, J.W. 2008. Continental West-Germanic Languages. In G. Cinque and R. Kayne (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Syntax. New York: Oxford University Press.

1 The number of languages and syntactic phenomena in the project can be extended or reduced if necessary.