Seeing the Romans - and ourselves - in a different light

Globalisation means becoming globalised, a process in which material culture plays a crucial role. This is what Miguel John Versluys, the new Professor of Classical and Mediterranean Archaeology, teaches. He bases his teaching on research into the origin and growth of the Roman Empire from the 3rd century before Christ. His inaugural lecture is on 29 September.

It is common knowledge that humans and the landscape in which they live have an effect on one another. Versluys also introduces the concept of objectscape. What applies for humans and landscape also applies for mankind today and the 3,000 to 5,000 objects that we come into contact with every day. 'Objects direct us and often involve all kinds of unintended changes,' Versluys explains. The most obvious contemporary object to which this applies is the smartphone. 'I sometimes even have to remind my children that they can actually use it to make a call.'

Ritual addition

There has always been a mutual relationship between humans and objects. In 222 BC, the Roman consul Marcellus made a crucial conquest of the Celtic tribes. One of the most important trophies was the magnificent set of weapons of the Celtic leader who had been slain in battle by Marcellus himself. ‘The Romans had never seen anything so beautiful,' Versluys remarked. 'Weaponry in Rome was dedicated to Jupiter and so was ritually included in the Roman objectscape. Anything that was unusual, as this was, was incorporated into Roman culture.'

Emotional influence

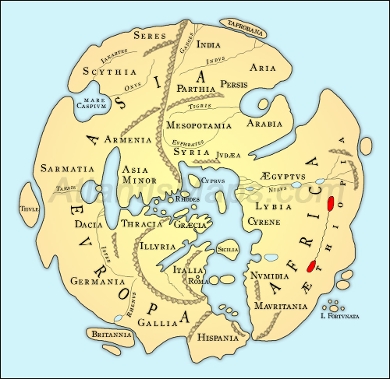

And it did not stop there. From the second century BC, Rome conquered large parts of the then known world. The conquest of the Hellenistic city of Syracuse on Sicily (a cosmopolitan hub), along with the conquests in Macedonia, Epirus and elswhere, even into Egypt, brought Rome an enormous number of artefacts: glass, reliefs, paintings, plates and dishes (made of agate), books, statues, gold, metal, precious stones, and also obelisks. Rome became Hellenistic, as it was called, but that was not all. All these objects may indeed have changed Rome - the Roman public space took on a different function and a different outward appearance - in a practical and also in an emotional sense.

The Other and the Self

Versluys: ‘Rome suddenly had an enormous amount of Hellenistic Other and drew an impressive piece of world history - geographical and chronological - within its walls. This confronted the still young Roman Empire with the call for legitimacy and identity: who are we, what are we doing here and where are we going? What is our Self? Rome did not yet have a narrative, it hadn't yet formulated an appropriate past.'The answer came after two centuries of discussion, in around the year zero, including in the form of Virgil's Aeneiad - Rome's own Old and New Testament, according to Versluys, and in the form of enormous and successful cultural and technical innovations. Founded on what had been tried out over several centuries and found to be useful, chosen from what was most useful and attractive from all 'spoils of war': from industrial and agricultural innovations, such as glass-blowing and books on developments in religion and philosophy, to the use of linen and the introduction of - divine - kingship. Emperor Augustus incorporated all this in the Roman Empire. A new Roman canon came about, based on the Empire's conquests.

Objects are also players

Versluys believes that we should not provide objects with an identity, but should regard them in terms of what they bring - or can bring - us, and what the unforeseen effects could be. We should look at them in the light of their interchange with people. 'Seen in this way, objects are also players.' Globalisation: that's also of all times.’ Versluys: ‘It mayu seem handy to think in terms of people and nation states to create order in a complex world, but that doesn't reflect the reality. The local context is always related to the global. Communities always adopt the best and most useful aspects of other communities and integrate them in what they regard as their own culture.' This is because the need for one's own culture to which one can belong is always present, see the Romans. Even though this own culture is actually fiction, given all the elements that have been incorporated into it. 'Seen in this light, Princess Máxima's speech in 2007 that there is no such thing as the Dutch identity is understandable and true, as is the commotion that this incited.'

Professor Miguel John Versluys received a VICI award in 2016 for his innovative interdisciplinary research on Innovating objects. The impact of global connections and the formation of the Roman Empire (ca. 200–30 BC). Together with Professor Ineke Sluiter and others, he is lead applicant of the NWO Gravitation project Anchoring Innovation, a ten-year study of innovation processes in antiquity.

Professor Miguel John Versluys received a VICI award in 2016 for his innovative interdisciplinary research on Innovating objects. The impact of global connections and the formation of the Roman Empire (ca. 200–30 BC). Together with Professor Ineke Sluiter and others, he is lead applicant of the NWO Gravitation project Anchoring Innovation, a ten-year study of innovation processes in antiquity.