Children learn early on that scientists are men

When children were asked to draw a scientist, a bald, middle-aged man in a white coat was most often depicted. Why is that? A group of Leiden University science communication researchers discovered that children already get this impression in primary school. Published in PLOS ONE on 16 November.

Master's thesis

Along with several colleagues, Anne Kerkhoven conducted a study for her master's thesis on the roles of men and women (and boys and girls) in teaching materials for primary school children. They investigated how and how often men and boys, and women and girls are depicted in online science teaching materials. All co-authors work at the Faculty of Science: at the Department of Science Communication and Society, Leiden Observatory and the Mathematical Institute.

Online teaching material

The researchers examined items for primary school children in two popular online databases that provide teaching materials, Scientix and OERcommons. These materials included experiments, demonstrations, assignments, videos and games on astronomy, chemistry, biology, geography, mathematics, physics, engineering and technology.

Stereotyping with men and women...

One of the findings was that, in these pictures and videos from the teaching materials, professions in the science sector were depicted as being filled by men 75% of the time and by women only 25%. Women were found to be over-represented as teachers: 63.9% of the teachers were women, compared to 36.1% men. Thus, the researchers conclude that the male-female ratio in the science sector is already out of balance in the teaching materials used in primary schools. That's a problem, given that children’s awareness of stereotypes rapidly increases between the ages of 6 and 10, specifically in primary school.

…but not with children

It is notable that the creators of the materials indeed paid careful attention to gender bias in the children they depicted: the researchers found only minimal differences in the number of boys and girls and hardly any difference in the roles they were assigned in the teaching materials. The creators of the materials apparently avoided stereotyping children, but seem to have forgotten to apply the same standards to the adults.

More women in science, but still not enough

In 2013, the percentage of women in science professions worldwide was 28.4%. These numbers have certainly improved over the decades. In 1960, 27% of biologists in the United States were female, while in 2008, that number was 52.9%. For engineers, these percentages were 0.9% in 1960 and 9.6% in 2008. Despite the improvement, most science fields are still dominated by men.

All science bachelor's programmes and all science master's programmes at Leiden University.

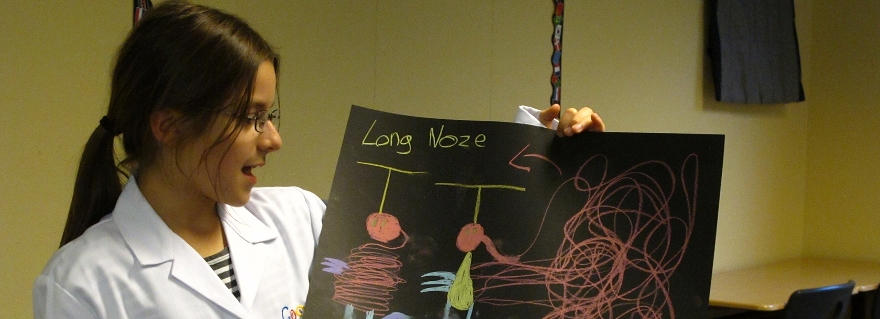

Photos: Universe Awareness, a teaching programme at Leiden University provides activities for girls to increase their interest in science and technology. Credit: UNAWE

Recommendations

The researchers have made a number of recommendations for a more balanced image of science subjects in school. This may help ensure that more girls choose science in university.

- Teaching methods, assessment methods and teachers’ attitudes should not be gender biased. This should prevent girls from getting the message that science is something for boys and not for girls.

- What is important is how men and women are presented, both linguistically and visually. Visual inspection of an English language book depicted men working twice as frequently, while women were shown as victims more frequently or filling care roles. If this one sample is representative of reality, a balanced image is needed in teaching materials, the researchers state. This way, children’s perceptions can be adjusted.