Rethinking history

Aiming to create a better understanding of Africa's past, a team of multidisciplinary researchers at Leiden University digs in to everyday artefacts and local knowledge. Their work helps to invalidate false assumptions and make less dominant narratives available.

Diversity is a basic need

Using daily artefacts and local knowledge, archaeologist Sada Mire not only collects fresh evidence on Africa's past, but challenges presumptions about history at large. She remembers how she dug up a sheep bone in Kenya, indicating that the people of its days had kept cattle, rather than 'just' hunting and gathering. Yet, the layer of ground in which she found it dated back to 1500 BC – thereby debunking the popular notion that hunting & gathering were followed by keeping animals, which only then leads to farming.

‘History is not linear, but circular,’ she believes. ‘People have mixed survival strategies; they use those which are most appropriate at that particular moment in time. During the Somali war, the 'modern' people in the cities suffered, whereas the 'traditional' pastoralists, who keep livestock, managed to survive as they knew the resources of the land. Diversity is a basic need for the survival of humankind.’ In her recent research in Somaliland, Mire studied rock art, landscapes and the practices of the people of the Horn of Africa. Her findings show that, besides self-sufficiency economy, there is also a wide diversity in religious identity. Leiden's Faculty of Archaeology allows her to pursue a holistic approach, and make less dominant narratives available.

Understand our place in time and space

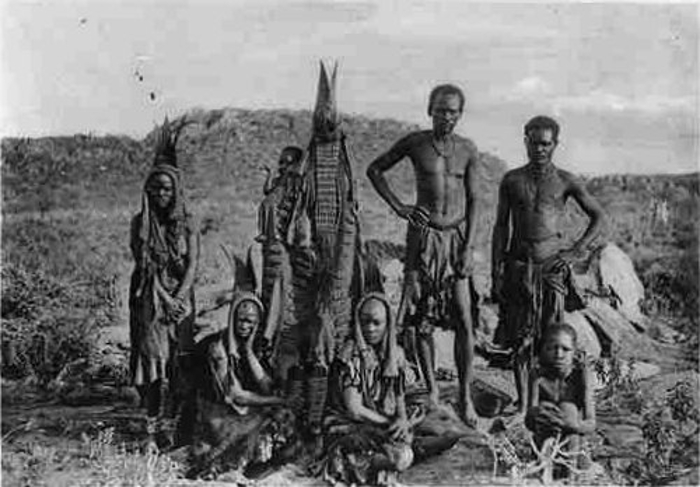

Rethinking African history may also help Europe reflect on its own place in global society. During field research in Namibia, several Herero informants told Jan-Bart Gewald how German soldiers used to cook the bones of their men. Initially, Gewald took it as a symbolic story, illustrating the horrors of the Herero genocide that had followed General Von Trotha's 1904 Vernichtungsbefehl (extermination order) to kill all Herero who refused to leave their lands.

However, when digging into the archives, he found it had actually happened. The evidence had been there all that time, he recounts, but no one had ever looked into it from that point of view. German soldiers had indeed boiled the heads of killed Herero to prepare specimens that could be used in the now debunked pseudo-science of craniology.

Sadly, he realises, such cruel histories have taken place not only in Namibia, but all over the continent. ‘Europeans tend to think of Africa as a place that needs to develop. Most have no idea of institutions like the Timbuktu University, of the trade relations we have had for hundreds of years with African countries, or of the repulsive acts Europeans committed there. We need that knowledge to understand our place in space and time.’