‘Surgeons and rowers have a lot in common’

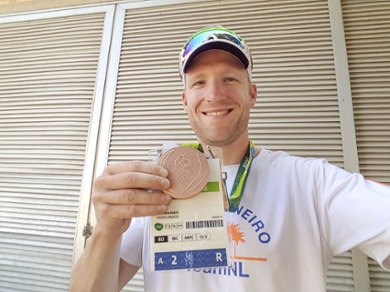

Rower Boudewijn Röell (31) already has one Olympic medal, but he's hoping to win another in Tokyo. 'At some point, though, you do have to stop.' Easier said than done in a time of corona.

This article appeared previously in our alumni magazine Leidraad

In 2012, medical student Boudewijn Röell was still in the under 23 team, but shortly after that, when he was 24 he picked up his studies again: 'I stopped doing sport altogether. Over the following months I ate nothing but fast food and of course I soon got very chubby. The wake-up call came from a friend, who gave me a kick up the backside, and I started training to go skydiving. I shed 13 kilos in two months, which got me down to 97 kilos. Then my former coach asked me if I wanted to take part in a rowing competition. I was absolutely amazed to come second. That was the start of my second rowing career.'

He exchanged his home in Leiden for Amsterdam, to live closer to the Bosbaan, a rowing lake in the city. His dean gave him the go-ahead to combine his top-level sport with his studies. In the 'eight plus cox', Boudewijn won bronze three times in succession: at the European championships in Seville in 2013, the World Championships in France in 2015 and with the Dutch Eight at the Games in Rio in 2016.

Once again, after these successes, Boudewijn decided to prioritise his medical studies, this time on the grounds of his - relatively! - advanced age. 'After Rio I didn't rate my chances in the Olympic Games in Tokyo as very high. I'd be 31 by then. The younger guys are champing at the bit to claim their place in the competitions. I also realised that I felt less motivated. My friends were getting on with their lives; they had jobs, relationships, were living with their partners. The sport was going fine, and I was living with my girlfriend at the time, but my studies were suffering. Not only that, in 2013 my income from rowing meant that I was the first among my friends with a good salary, but in 2016 it was different story.'

So, in 2016 he decided to slow things down, although he didn't give up rowing completely. 'I was trying to get a better balance; I wanted to make time for other important things in my life.' He exchanged his punishing programme of training fifteen times a week for daily sessions on the Bosbaan between seven and eight in the evenings, once he had done a full day as a surgical resident in Gouda. In 2018 he came back to Leiden.

Still getting stronger

He still had very little time for a social life. ‘Top sports people go for years without ever being drunk. After every party you have to make sure you're home in bed early. Holidays are also rare; at the end of 2017 I went on holiday for the first time in eighteen months.' Although Tokyo was not his immediate goal, his hunger as a sportsman for these Games continued to gnaw at him. ‘In practice, every top rower has a four-year cycle. If you're selected, you don't stop just before the Games.' During the selection, he proved to be strong enough for the Eight, but coach Mark Emke put him in the Four.

He feels that his strength is still increasing. 'Maybe less explosively than before, but that explosiveness is something I've always had to rein in.' Rowing is an incredibly tough sport, and it demands huge reserves of strength. Boudewijn is tall - very tall - and he regularly lifts 220 kilos. ‘And I'm not the only one in my team; we have the strongest Four ever.' Rowers are in it for the sport and the performance, he says, not for the status or the money. 'In a season there are five - maybe six - important competitions, each lasting six minutes. That's what you put the rest of your life on hold for.' It's also a very fair sport: the people who work hardest achieve the most. 'And that suits me, because I always want to be the best version of myself, whatever I'm doing. I'm also very competitive; everything is a contest.' He gives an example: 'At training camp I would often run up the hills, rather than going in the lift to the summit. That started as just a little extra effort, but at some point other team members also joined in, so we turned the sessions into contests on Strava. All the way to the summit in one and a half hours with a heart rate of 180. It's now a regular part of the training.' He intersperses anecdotes with personal reflections, with boundless enthusiasm and not the slightest trace of self-importance.

Boudewijn Röell is a relaxed and easy conversationalist, who waxes lyrical when talking about his sport. He uses his whole body to demonstrate the relatively slow, controlled movements of rowing, and emphasises that it calls for ultimate precision, in harmony with the rhythm of the other rowers in the boat. If things are going well, he doesn't give that a moment's thought during the competition; it's all automatic. After the initial strokes, the rowers find their flow, and the boat seems to cut effortlessly through the water. It's only once they've passed the finishing line that they realise how exhausting it was. ‘Strangely enough, that's when you also realise what you've achieved as a team. During the competition, you're focused completely on yourself; you're not thinking of anything else. Quieting your thoughts, emptying your head, losing yourself completely in physical exertion - that is just so cool.'

No sporting ambitions in the family

It sounds as if there's no need for any strategy, but appearanes can be very deceptive: 'You decide in advance: an explosive start or a controlled build-up. Sometimes, it works out differently, and you get off to such a good start that you're out in front. Then there's no need for discussion; we just ditch the strategy we'd decided on. What's good about rowing is that you can always see who's behind you; there's no other sport where that happens. If you're in front and pulling ahead, it really motivates you, but it's a different story if a team that was behind you suddenly streaks past. And if you're trailing behind from the start, it's a lonely place to be. You can't see whether you're doing things right or not.'

It was no surprise that Boudewijn opted to study in Leiden in 2006. His sister was studying psychology in Leiden and he preferred not to be too far away from his parental home in The Hague. Boudewijn had never rowed but he was a fanatical sportsman. ‘My father was an officer in the marines and after that he worked for the Royal Family. My mother was an HR manager. My father and I still go on strenuous walks in the Swiss mountains, but my parents have never had any sporting ambitions. One of my uncles was a rowing instructor, but I hardly knew him. It must be something I was just born with.' His rowing career kicked off in his first year as a member of Quintus. 'One of the other members suggested rowing together with a few friends at Asopos de Vliet. Our eight didn't win a single prize, but it was so much fun. Those guys are still my closest friends.' Boudewijn wanted more, and his talents were recognised. He made it to the Men's Eight, transferred to national level in 2007 and in 2010 and 2011 was part of the under-23 Eight in the World Championships.

Biography

- 12 May 1989 - Born in Leidschendam, the son of Ir. W.F.A. Baron Röell, former adjutant to Queen Beatrix

- Started his medical studies in Leiden in 2006

- Was a member of Quintus and Asopos de Vliet

- Bronze medal at the European Championship in 2013

- Bronze medal in the World Championship in 2015

- Bronze medal in the Holland Eight at the 2016 Olympic Games

Fine motor skills

As Boudewijn became more successful, his dean gave him more and more room for his sport. Since 2017, he has known that his future after rowing lies in surgery. Surgeons are very dependent on their fine motor skills, which is not something you would expect from a strong rower. ‘Yes, you would,' says Boudewijn. ‘Finetuning is the key to success for a rower. It takes a lot of careful and precise adjustment to position the oars perfectly to give you the optimum performance. It really is very finicky. Just the other day, when we were rowing with new carbon oars, despite all our highly exact measurements, they simply weren’t handling properly. It didn't feel right, so we had to figure out why. We learned that once the blades were submerged under the water, they deformed a few millimetres due to the high pressure. You can really feel that, even though it's such a minute difference. I think that's exactly what characterises a surgeon - that striving for absolute perfection. During a medical procedure, too, you get into a flow where your only thoughts are about what you are working on at that moment.’

He has no doubt that his rowing career helps him to become a good surgeon in other ways as well. ‘I've learned to perform under pressure, keep my nerves under control and how to make sure I have a healthy lifestyle. Rowers also always take responsibility for their own actions: that’s an important trait for surgeons, too. And during his internships he has seen that, just like rowers, surgeons never lose their cool.

And then came the lockdown

At the beginning of this year, Boudewijn was well on his way to his last sports performance on the world stage, before finishing his studies. And then came the lockdown. Rowing was no longer possible and the Games were postponed. So there he was with his solid plan, trapped in his house on the Herenstraat. 'I have to say that it took me a month of hard work. I knew - and know - that I can be kicked out of the Olympic Team if I do my internships before the Games. So now I'm in discussion with the dean to see if I can postpone the internships until after the Games in 2021'.

Unsurprisingly, this dedicated rower did not end up squandering his time on binge-watching or online gaming. ‘I cycled a lot - it was beautiful weather - and was given an ergometer by Asopos. I was also able to train a lot with one of my friends. And all of a sudden I had time for some party tricks I'd always wanted to learn, like doing handstand push-ups.’ He needs little encouragement to get down beside his chair and give a demonstration. The interview continues with Boudewijn upside down and vertical, doing push-ups. Then you know you’ve got a future surgeon in front of you. Once Boudewijn Röell has set his mind on something, nothing is going to stop him.

Text: Fred Hermsen

Photos: Frank Ruiter/Leidraad