Life sentence for Mladić: mission accomplished?

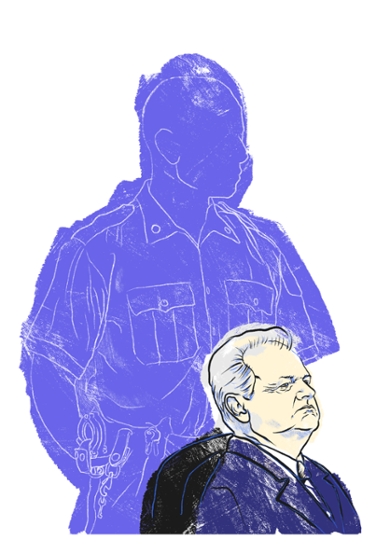

The court has dismissed Ratko Mladić’s appeal and upheld his life sentence for genocide and war crimes. The verdict is one of Yugoslavia tribunal’s last. Mission accomplished?

Note: this article was published in 2020 and was updated on 8 June 2021 with the latest news.

‘Mr Praljak, please take a seat,’ said the judge at the Yugoslavia tribunal on 20 November 2017, in a friendly but firm manner. But Slobodan Praljak refused to sit down. The Bosnian-Croatian general had just been sentenced to 20 years imprisonment for war crimes, but he refused to accept the judgment. ‘Slobodan Praljak is not a war criminal,' retorted the large man with the white beard and the bulbous nose, referring to himself in the third person singular. 'And I therefore reject your judgment.' He raised a small phial containing the fatal substance potassium cyanide to his mouth and emptied it in one go. The cameras turned away, a curtain in front of the public dropped down and shortly afterwards Praljak died.

A few kilometres away, Carsten Stahn was following the proceedings on his laptop. He was in shock, he recalls. Suicide before the eyes of the whole world; it was too absurd to be true. At the same time, the Professor of International Criminal Law was also fascinated by the story behind the act. Every judge or lawyer will agree that the court is also a theatre in which everyone has his or her own role. Seen from this viewpoint, Praljak's self-appointed death was the ultimate final act, one where he spat for the final time in the eye of the court and refuted its legitimacy.

In his new book, Stahn takes us with him behind the scenes of this theatre. Legacies of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia is the definitive evaluation of the Yugoslavia Tribunal (ICTY) that was established in The Hague in 1993, following some 10,000 days of proceedings, 161 indictments, 4,650 witness hearings and one suicide. The higher appeal by former General Ratko Mladić is the only remaining case being heard. How successful was the tribunal? What has it taught us about international criminal law? And what problems did the ICTY come up against?

The cover of the book bears an intriguing photo. We see a man in a three-piece suit playing his cello on top of the remains of a destroyed building Why did you choose this particular image?

‘The man in the photo is Vedran Smailović. He is playing here on the ruins of the library of Sarajevo, during the siege of the city by Serbian troops [from 1992 to 1996, ed.]. For me this is a symbol of hope. During a war, attempts are often made to destroy the culture and identity of the enemy, but this photo shows clearly that culture always resurges and flourishes again, even in the most devastated places. The Yugosavia tribunal does more or less the same thing. It cannot erase the crimes of the past, obviously, but it can send out a signal about hope for better times.’

The siege of Sarajevo was one of the atrocities during the different wars that followed the break-up of the former Yugoslavia. The Bosnian capital was surrounded for years by Serbian troops, who bombarded the low-lying city with gunfire from the surrounding hills, killing more than five thousand civilians. The Yugoslavia tribunal was set up while the siege was still going on, to carry out research on violations of human rights from 1991.

With our present-day knowledge, can we say that the Yugoslavia tribunal was a success? Mission accomplished?

‘It is a coincidence that you use those words because that is precisely how court chairman Carmel Agius expressed it in his final address to the UN Security Council: mission accomplished. And there are some facts that do bear out this conclusion. There are, for example, no more fugitives. In total, 161 people have been indicted, and all of them have appeared in court. Moreover, Milošević, Karadžić and Mladić have also stood in the dock. That is very important because it gives a clear signal that the leaders do not get away with war crimes.’

That's something I wanted to ask you about. If you could choose, what judgment from the history of the tribunal do you think has been the most prominent?

‘The main victory has not been one single case. The most important contribution of the ICTY is that it broke with the past. The tribunal has shown successfully that you can punish crimes that were committed a long way away. It is not just about punishing those who committed the acts, but also the communicative and even pedagogical impact on the society where the crimes took place. You listen to the perpetrators and the victims, and together you reconstruct what happened. And, even more important, why it happened.'

There are some critics who believe the sentences are far too low. Only one sentence of life imprisonment was handed down.

‘There are indeed many people who judge international tribunals on the basis of the number of convictions, but it doesn't work like that. An acquittal also shows that a fair and careful process has taken place, that the law and justice have prevailed. The ICTY did a lot of preparatory work here. The tribunal invested heavily in improving the defence of suspects, in order to make sure there was no imbalance between the accuser and the lawyers.'

‘Even so, the sentences are relatively low. That gives rise to some problems in the international community. The first war criminals are now being released because they have served two-thirds of their sentences. Tensions could rise again when they are returned to society.'

Stahn shows in his book that there are more challenges, open ends and uncertainties. Although the Yugoslavia tribunal did bring all the fugitives to court, the 672-page report of the proceedings shows that the court had many tough nuts to crack. For example, the deterrent effect of the brand-new court was not enough to stop the violence in Yugoslavia. And more important: the most serious crime was committed after the court had come into being. In 1995 more than eight thousand young boys and men were murdered in the Muslim enclave of Srebrenica.

What would you say is the biggest challenge that the Yugoslavia tribunal has not been able to resolve?

‘That it has not been able to bridge the differences in the country's society. In particular in Croatia and Serbia you see that the nationalistic narratives are still enormously persistent, in spite of the sentences. War criminals still feature prominently and are honoured as heroes. That's terrible, because the real grievances of the conflict are still there.'

What can other tribunals and courts, like the International Criminal Court (ICC), do to avoid the same happening again?

‘Clearly, outreach has to be an important part of the work. The Yugoslavia tribunal used witnesses mainly for evidence in court. But if you really want to heal the wounds, you have to go into the communities that have been affected. Explain how a criminal court works, why a judge arrives at a particular decision. And also use political initiatives to achieve better relations between neighbours, just as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa did.’

And now another problem is rearing its head: the power of authoritarian leaders. They regularly let it be known that they have no interest in 'interference' from international courts. American President Trump, for example, announced in June sanctions against staff at the International Criminal Court who are examining possible Amerian war crimes in Afghanistan. 'Washington and the ICC at loggerheads‘ was a recent headline in Dutch national newspaper Trouw.

Are you not concerned that this will mean the end of international courts that have been painstakingly established in recent years?

‘We are indeed seeing signs of a backlash, mainly caused by those who are unhappy about the far-reaching globalisation that typifies today's world. But we mustn’t forget that the biggest contribution of international institutions takes place outside the spotlight, where people work together effectively on a daily basis. Moreover, a stable international legal order is often in the interests of the big powers like the United States. And most American governments acknowledge that. You could even say that there's no other country that has done so much for international criminal law: America was a firm proponent of the war tribunals in Nuremberg and Tokyo, as well as the Yugoslavia tribunal. The same applies to legal cases against war criminals in Uganda, Libya and Sudan.'

How do you see the future? Is the Yugoslavia tribunal a blueprint for the years to come?

‘No, I wouldn't say that. What you see is that international law is becoming increasingly pluralistic. Tailor-made responses are being devised for each separate situation. In Chad, for example, a hybrid court was set up against former dictator Hissene Habre that operated partly nationally and partly internationally. Syria has never joined the International Criminal Court, but national courts in Spain and Germany still managed to put a number of criminals behind bars. Ways are found at different levels to get justice for victims.'

Text: Merijn van Nuland

Images: Pirmin Rengers

Free online course on international law

If you would like to know more about international law, you can follow the free MOOC International Law in Action. The course is offered on the Coursera platform and Carsten Stahn is one of the lecturers.