‘A doctor! You?’ Three women on their PhD and career

Rietje Knaap’s (83) PhD was a real feat of endurance, but she persisted. ‘You’re married so you don’t need a pension, do you?’ What are the experiences of Knaap and women who followed in her footsteps? In the run-up to International Women’s Day on 8 March, three generations of female doctors look back in this long read.

Leiden, September 1955. Eighteen-year-old Rietje had left her parental home in the village of Babberich in the eastern province of Gelderland and moved to Leiden to study biology. She was a keen learner and her parents had encouraged this. Now, 65 years later, Knaap looks back at this turbulent time. ‘My father, who was a GP, had studied in Leiden so he thought I should study there too.’ As a brand-new first-year student, she moved into a room on Groenhovenstraat with primitive sanitary facilities and an otherworldly landlady. She plunged headfirst into her new life, joining the Society for Female Students and throwing herself into her studies.

How about the proportion of men to women today?

In 2019, for the first time ever, more women (226) than men (207) received PhDs at Leiden University. The number of female professors increased too: from 23% in 2014 to 29.7% in 2019. This means that Leiden is in second place in the Netherlands, after the Open University (34.7%). The number of female professors may have increased, but the increase is out of proportion to the number of female students (60%). Where are things going wrong? Of all the University staff, 44.6% were women in 2019, and almost equal numbers of women (49%) and men started a PhD programme after graduating. Then the numbers drop: of the lecturers, 46.3% are women and of the senior lecturers, 38.8%. With its diversity policy, the University aims to achieve a better reflection of society. One aspect of this is to promote gender equality, with tools such as optimising the appointments policy for women (professors in particular) and improving perceptions and communication.

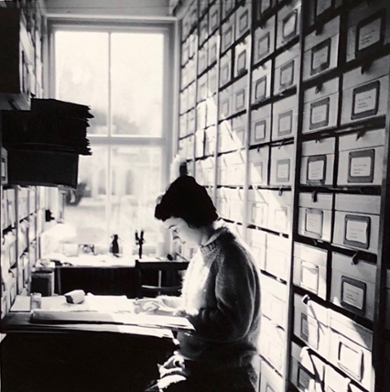

Working on the Flora Malesiana

The programme was very intensive: lectures in the morning, practicals in the afternoon and yet another practical, physics this time, on a Saturday morning. After graduating, Knaap chose to focus on plant taxonomy, classifying plants into species. Leiden was famous for this, with the Herbarium and Professor Cornelis van Steenis, an esteemed professor of tropical botany. He was director of the Flora Malesiana and it was under him that the flora of the whole Malaysian region was classified.

Biology was already a popular field of study with women and the proportion of men to women was almost equal, but female PhD candidates were the exception in those days. Knaap therefore felt most honoured when Professor Van Steenis asked if she wanted to do her PhD with him. Some members of her year group were astounded when she agreed.

All the housework

Knaap was 26 and already married when she began her PhD research. Her husband, Hein Knaap, a physicist who was made a professor in Leiden in 1968, supported her research, without having to make any sacrifices himself. ‘I organised my life in such a way that my Hein, who has since passed away, wasn’t affected by my work. I was responsible for the housework, did our tax returns, found schools for the children and got the cantankerous boiler working again.’

Zip undone

In the first year of her PhD, Knaap combined her research with a job as assistant to a professor. She helped him prepare his lectures and often went to the depot with him. ‘I’ve got a good anecdote about that. I once wore a short brown skirt and had forgotten to do up the zip. The professor was tremendously nervous that day. It had me wondering what was wrong with the man. When I got back to the department, my colleagues pointed out that my zip was undone. We had a good laugh about that. When the professor later left the University, there was a whole act about the episode, and he once again went bright red.’

Funding refused

Knaap had two children while she was doing her PhD research. How did she combine things? ‘You know, my dear, there was no such thing as parental leave in those days. We hired a girl for an hour a day to do some of the housework and help with the baby. I got to devote some uninterrupted time to my work while the baby slept.’ Knaap was awarded funding, but then for only one year, which meant she had to apply for funds each year that followed. PhD posts such as today didn’t exist at the time. Her request for a second year was initially refused. ‘I phoned the professor at the Dutch Research Council whose responsibility it was, to ask why I hadn’t received another year’s funding. He thought I should have been able to finish the research by then. I said that it was unheard of to finish a PhD in a year. He relented and granted me another year.’

‘I organised my life in such a way that my husband wasn’t affected by my work.’

‘You don’t need a pension’

After that year Knaap stopped requesting further funding. ‘I was pregnant with my second child and knew what to expect, so I finished my PhD research at my own expense, not at a Speedy Gonzales pace though.’ She took eight years to write her dissertation. ‘I never stopped working. I tinkered away at it every single day.’ Knaap received her PhD in the summer of 1972, the third woman to do so in the Netherlands that year. Afterwards, her former supervisor Van Steenis asked if she would like to work at the Herbarium ‘for an annual allowance.’ Knaap: ‘Allowance! “I want a job,” I said. Van Steenis replied that as I was already married I wouldn’t be needing a pension anyway.

A new chapter

The job came to nothing. Knaap: ‘I was fed up to the back teeth by then, and decided to stop looking in academia. There weren’t many jobs in tropical botany anyway, which was a Leiden specialism. I didn’t want a job too far away from Leiden – also because of my family.’ Soon after she applied for a job as a biology teacher at Rijnlands Lyceum in Wassenaar. The difference between the sexes vanished immediately. ‘Equal salaries, equal jobs. No fuss. It was emancipated there.’ She would devote her entire career to working as a teacher and rose up through the ranks too. Now, at the age of 83, she still has links to the school: she coaches talented children who qualify for Pre-University College.

Not bitter

With the benefit of hindsight, would she have made other choices? ‘No,’ she says resolutely. ‘It was incredibly interesting to work with such a fantastic collection in the Herbarium, and it was fascinating to work with visitors from all around the world. But I certainly wouldn’t say that women were encouraged, on the contrary. If you look at how hard I worked: I could be bitter about it, but I’m not at all.’

Biologist and phytopathologist Gera van Os (53)

‘I began as an external PhD candidate in Leiden in 1995. My research was into soil resilience in the flower bulb industry. I did the practical research during a temporary job for the Laboratory for Flower Bulb Research. I got the job thanks in part to a regulation stating that if two candidates were equally qualified, the job should go to a woman: in the last round of the application procedure, it was just me and a man, so I got the job. I found it a bit disappointing to get the job in that way. My colleagues weren’t aware of it, so didn’t judge me for it.’

‘I didn’t have to prove myself like regular PhD candidates do, so I didn’t suffer from prejudice at the University. But that was sometimes the case when I went to visit growers for the Laboratory. They were often a bit conservative and were taken aback to see a young woman had come to advise them. And they were suspicious of someone from a university anyway: a boffin like me would never have got their hands dirty.’

‘The growers were often a bit conservative and were taken aback to see a young woman had come to advise them.’

‘Toen ik uiteindelijk een vaste aanstelling kreeg - vanwege een wetswijziging, na acht jaar tijdelijke contracten - besloot ik ‘When I was finally given a permanent contract – after a change in the law, after eight years of fixed-term contracts – I decided to follow my heart and have children. I put the writing of my dissertation on hold and had two children. A year later, I bumped into my supervisor and he gave me the kick up the backside that I needed. I made an ambitious plan with my husband: he would look after the children every Saturday for half a year, so that I would be able to put my nose to the grindstone for my dissertation. In that time I also applied for a senior role, but my boss didn’t think that was realistic seeing as I didn’t work full time, had two young children and was trying to finish my PhD in my own time.

‘For years my doctor’s title served no purpose whatsoever, but now I’m a reader in sustainable soil management at Aeres University of Applied Sciences in Dronten, a role that you’re only eligible for if you have a PhD. Women definitely have equal opportunities here.’

Neuropsychologist Marcia Goddard (35)

‘I received my PhD in 2015 for research into the development of the brain and social behaviour. I didn’t face any prejudice during my PhD, probably because the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences is a real female stronghold. When I had my first child, I started to work from home a lot more. I didn’t feel bad about that. I can stand up for myself, but I can imagine that some women find that difficult if that isn’t the culture at the faculty.

‘People don’t expect a woman with a mass of curls and high heels to be a scientist’

‘After my PhD, I became a lecturer, but I switched to a job in industry a year later. A permanent contract at a university is like gold dust, and I’m responsible for my family. And I want to have an impact with my research rather than just writing for my peers. Winning the Dutch edition of FameLab, a science communication competition, only strengthened my resolve, so I found a job as a researcher at YoungCapital Recruitment, where I developed assessment tools. My current job, for &Ranj, a gaming studio, involves researching how to change behaviour.

‘Outside these companies, I do sometimes face prejudice. I was one of the speakers at an HR event, but the men ignored me at first. I’m half-Caribbean, have a mass of curls and like wearing dresses and high heels. The men were surprised to discover that I was the speaker and had a PhD: “A doctor! You?” When they hear the word scientist, many people still think of a middle-aged man with glasses. I could laugh it off because I already had a job, but situations like that are very frustrating for women who still have to prove their worth. Times have changed and open discrimination against women is no longer allowed, but you can’t change patterns at the drop of a hat. I believe that a whole generation will have to have left the positions at the top before change can come.’

Text: Linda van Putten

Mail the editors