Pilgrim Year: a commemoration rather than a celebration

Myths abound about the Pilgrims, the group of religious refugees from England who set sail for America in 1620. Did they really live in peace with the indigenous peoples of America? In an international conference, historians from Leiden will seek to draw attention to the more negative effects of the colonisation of North America. They will also look at the Pilgrims’ Leiden period.

The Pilgrim Fathers, as they were long called, are often viewed as the early founders of the American nation. In 2020, it is exactly 400 years since these English migrants embarked on the Mayflower to cross from Plymouth in England to North America; numerous exhibitions, conferences, books and commemorations are marking the anniversary of their voyage. On board of the Mayflower were 100 English passengers. Half of them, radical Puritans who had separated from the Anglican Church, had found refuge from religious persecution in their home country and lived in Leiden from 1609 to 1620.

In 1620, a first group of 53 Pilgrims left Leiden to establish a second English colony in America, Plymouth Colony, together with nearly 50 other English men, women and children who joined them when they embarked in England. These 100 passengers (and the two babies that were born during the voyage) are now called the Pilgrims. In the new colony, they introduced relatively democratic forms of governance that may have influenced the later political system in the United States.

Painful history

‘People in England and the United States used to think of Mayflower anniversaries as occasions for celebration,’ says Leiden American Studies expert Johanna Kardux. ‘But in the past ten years or so more attention has been paid to the devastating effects for the indigenous peoples. That’s why we prefer to call it a commemoration.’ Kardux and her co-author historian Eduard van de Bilt published the first edition of their book Newcomers in an Old City: The American Pilgrims in Leiden 1609-1620 in 1998. A fourth, revised edition will come out this spring.

International conference

Together with Leiden city historian Ariadne Schmidt, Kardux and Van de Bilt are also organising a conference this summer Four Nations Commemoration: The Pilgrims and the politics of memory (26 - 28 August). Kardux explains: ‘Focusing on the way the Pilgrims’ story has been remembered, memorialised, and mythicised over the centuries, we have chosen to take a four nations perspective, referring to the four “nations” involved in the Pilgrim commemoration: England, the Netherlands, the United States and Native America, the original inhabitants of America. Obviously the latter are not one nation. The title is intentionally a bit provocative to draw attention to indigenous perspectives on the history of the foundation of Plymouth Colony and its memorialisation.’

A selection of activities in the first half of Leiden 400:

- 15 February Heritage Leiden: Ancestor Booth. A curator will help you trace your ancestors

- 27 March - 12 July Exhibition at Museum De Lakenhal: Pilgrims to America 1620-2020: Boundless Liberty?

- 9 April - 26 November Exhibition at Hortus botanicus Leiden: From Columbus to Mayflower

- 15 May - 4 July Exhibition at Museum Volkenkunde, The National Museum Of Ethnology: First Americans

Native American perspective

‘The Native American perspective was neglected for a long time,’ notes Van de Bilt. ‘It only really began to receive attention after the Second World War, and it is only in the past ten years that much research into this field has been done at all.’ The Pilgrims who founded Plymouth Colony were a small group whose worldly ambitions, according to contemporary sources, were relatively modest. Kardux: ‘They had to be if they wanted to survive. Manuscripts from the time also show that they really were interested in the local indigenous culture.’

Stark contrast

Many more English Puritans arrived in America to found the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1630, with the number of newcomers rapidly rising to 20,000 by 1642. This led to more conflicts with the indigenous population of the area, which the British explorer John Smith had previously named New England. Kardux: ‘This large group obviously had much more of an impact. The Pilgrims’ first romanticised Thanksgiving celebration in 1621 is in stark contrast to the true effects of colonisation and the diseases that had already been brought over, which decimated the indigenous population of North America.’

Myth-making about Thanksgiving

The myth of first Thanksgiving in 1621 has it that after a harsh first year in which half of the Mayflower passengers had died, the Pilgrims invited the local Wampanoag tribe to celebrate the first harvest. However, this, like other stories about the Pilgrims, is a 19th-century invention. The Wampanoag were an indigenous tribe who lived where the Pilgrims settled in New England and signed a mutual-defence treaty with them. The Wampanoag, however, as a recent as an article in The New Yorker explains, tell a different story. According to the story that was passed down from generation to generation in Wampanoag culture, there was a celebration, but the tribe had not initially been invited. Hearing the gunshots with which the Pilgrims were celebrating the harvest, a group of Wampanoag warriors came rushing up because they thought the English were under attack. The Wampanoag version of the story has it that the English doubted their good intentions at first, but ended up sharing the meal with them after all. Though perhaps no less mythic, this story nowadays has more traction in the media than the traditional one.

Arrival of enslaved Africans

Van de Bilt mentions another recent discussion in The New York Times: in 2019 it dedicated a series of articles to 1619, the year before the arrival of the iconic Mayflower. This is when the first Africans were brought to Virginia. Van de Bilt: ‘The myth that it all began with the Pilgrims in 1620 is debatable: these Africans, the first “slaves,” arrived before the English Pilgrims. Some historians argue that in the longer term slavery promoted a feeling of equality among white Americans, thus indirectly fostering democracy, albeit a democracy based on the fundamental inequality of millions of enslaved and indigenous people. From this perspective, it is not just the Pilgrims who arrived in 1620 that stand at the cradle of American democracy.’ What is more, English colonists had already settled in North America more than a decade earlier: they founded the first English colony, Jamestown in Virginia, in 1607.

Native Americans to speak at conference

One of the keynote speakers at the conference in Leiden is Jean O’Brien, a history professor at the University of Minnesota and Native American, citizen of the White Earth Ojibwe Nation in Minnesota. She is co-author of a book about Massasoit, the leader of the Wampanoag. Massasoit (the native word for ‘leader’; his actual name was Ousamequin) was present at the first Thanksgiving in 1621. O’Brien also debunks the myth of a serene meal to celebrate the peace because this disregards that the Wampanoag was a dynamic ethnic group under pressure from disease and colonisation. In her keynote lecture at the conference, which will be open to the general public, O’Brien will look at the myths and memorial culture surrounding Massasoit. A couple of members of the Wampanoag nation will also present papers at the conference.

Pilgrims’ sojourn in Leiden

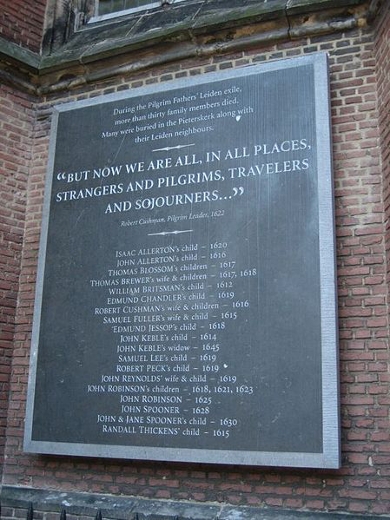

The conference will also look at the Pilgrims’ sojourn in Leiden. The group that we now call the Leiden Pilgrims had originally fled from England to Amsterdam in 1608, but in-fighting within the separatist English religious community that was already established there led the group to request and be granted permission to settle in Leiden in 1609. In those days Leiden was the second city after Amsterdam in the Dutch Republic and it was general knowledge that the city had welcomed thousands of Protestant refugees from the south (now Belgium and Northern France). The group most certainly also chose Leiden because it had a university, says Kardux. Their pastor John Robinson had studied theology at the University of Cambridge.

Loss of identity

Internationally, little attention has been paid to the Leiden period, says Van de Bilt. American descendants of the Leiden Pilgrims usually know the story, but the same is not true for the general public. Kardux: ‘In our book we expressly treat the Pilgrims as migrants, who like other newcomers were afraid of losing their identity because their children were gradually assimilating into Dutch culture.’

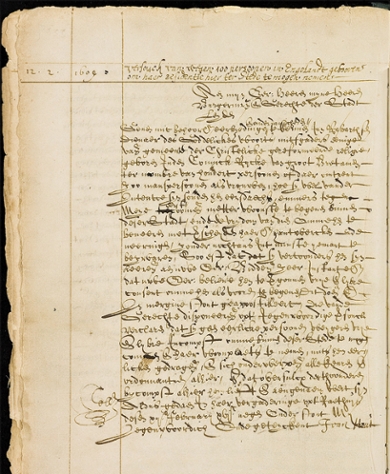

Seventeenth-century manuscript

The main source for the early 17th-century history of the Pilgrims is a book chronicling the founding and early history of Plymouth Colony by Pilgrim William Bradford, who also lived in Leiden and was many times re-elected as governor of Plymouth Colony. His book Of Plymouth Plantation is one of the classics of American history and literature. Bradford devotes a whole chapter to Leiden. He is relatively positive about Leiden, which he calls ‘a fair and beautiful city’, says Van de Bilt, and explains why they had come to Leiden, what their life was like there and why they decided to leave again in the end.

Long arm of the English law

A few factors prompted the Pilgrims’ departure. Even in Leiden, the English separatists were not safe from the long arm of the English law. Moreover, they were afraid that the second generation would assimilate too quickly. Kardux: ‘Parents saw how their children preferred to go ice skating with their Leiden peers on a Sunday rather than going to church. They saw themselves as English men and women rather than new Dutch citizens.’ Van de Bilt points to the hard life they had here. ‘The Pilgrims found work, but many of them earned very little as unskilled workers in the textile industry.’

Nine presidents are descendants of Leiden Pilgrims

Genealogical research has shown that nine American presidents are descendants of the Leiden Pilgrims. Barack Obama, on his mother’s side, is a descendant of the Leiden Pilgrim family Blossom. Ironically, the Bush family, with Presidents George Bush senior (who visited Leiden in 1989, see photo: National Archive/Rob Croes) and son George W. Bush, are also descendants of the same family. This makes Obama and Bush distant relatives of each other. Presidents John Adams, John Quincy Adams, Ulysses Grant, Calvin Coolidge, Zachary Taylor and Franklin Delano Roosevelt are also descendants of the Leiden Pilgrims.

Ties with the University

We know that a number of Pilgrims had links with Leiden University. Their minister John Robinson was most interested in the heated theological debate between professors Gomarus and Arminius and their followers. Gomarus strictly followed the Calvinist doctrine of predestination and believed that people could not influence their own salvation. The more liberal Arminius, however, believed that human free will played a role too. Robinson publicly joined in the debate, choosing Gomarus’s side. The Pilgrims initially held their church services in Robinson’s house on Kloksteeg, but once their congregation had grown to a few hundred members they most probably held their Sunday services in the nearby Faliede Begijnhof Chapel at the University. Part of this former chapel is now a wing of the University’s Administration and Central Services department on the Rapenburg Canal.

Protection offered by the beadle

Some Pilgrims such as Thomas Brewer were enrolled at Leiden University. William Brewster, together with John Robinson one of the main leaders of the Pilgrims, tutored students in English. He and Brewer set up a secret ‘Pilgrim Press’ in his house on Pieterskerkchoorsteeg, an alley near Pieterskerk church, where he published separatist theological manuscripts that were smuggled to England. Both were arrested on the orders of the English king. Brewster escaped, probably with the help of the Leiden authorities. As he was enrolled at the University, Brewer was subject to university law, which came in very handy when the English demanded his extradition to England. The University beadle protected Brewer during his journey to Rotterdam. He was taken to England from there.

Anatomical theatre

According to Pilgrim historian Jeremy Bangs, other Pilgrims also attended the University. Myles Standisch, a military adviser, is thought to have attended lectures by engineer Ludolph van Ceulen, and Pilgrim doctor Samuel Fuller most probably learned about anatomy in the University’s anatomical theatre.

Leiden influences

Historians speculate about the extent to which the Pilgrims were influenced by their time in Leiden. A second keynote lecture at the conference in Leiden, by Puritanism scholar Francis Bremer, will address this topic. In America, the Pilgrims introduced the division of church and state, civil marriage and, as already mentioned, relatively democratic forms of governance – just as in the Dutch Republic. Did they draw their inspiration from the Netherlands? And was their first Thanksgiving influenced by the annual Thanksgiving service in Pieterskerk church on 3 October, celebrating the liberation of the city from the Spanish in 1574?

American innovations

The Leiden or Dutch influences should not be exaggerated, however, says Van de Bilt. Some ideas and experiences already dated from England. ‘The idea that the Pilgrims laid the foundation of the democratic tradition can also be linked to their break with the Anglican Church and the establishment of small, independent congregations in which there was also an important role for laypersons.’ And some American historians argue that the Pilgrims only came up with innovations once they were in America and that their relatively democratic forms of governance were an adjustment to the frontier conditions of the new colony.

No new myths

Kardux thinks that the Pilgrims’ pastor John Robinson was influenced by his stay in Leiden: ‘Robinson was an orthodox Calvinist, but he did to some extent become more tolerant in Leiden. We can see this in his letters to the colonists in Plymouth. He advised them to be open to the new conditions and to the indigenous population.’ But she also emphasises: ‘We want to call attention to their sojourn in Leiden, but we don’t want to start creating new myths.’

Picture above article: ‘The Embarkation of the Pilgrims’ (1857) by Robert Walter Weir. Photo: Wikimedia

Text: Linda van Putten

Mail the editors