A digital eye for archaeologists

Wouter Verschoof-van der Vaart is refining an artificial intelligence system that can detect and classify archaeological objects on digital images. Such a system is desperately needed because human archaeologists around the world are being flooded with data.

The Data Science Research Programme at Leiden University combines data science with PhD projects in a wide range of disciplines. The programme has been running for over two years, and is producing the first astonishing results. We discuss some of them in this series of articles.

Amazing, all the images that archaeologists are receiving nowadays thanks to satellites, elevation measurements and other forms of remote sensing. They can find undiscovered archaeological objects on the scans. But so much material is available now that it is impossible to look at it all manually. Over the last decades, archaeologists have developed algorithms that can find specific objects in a certain area, but these systems can’t be used universally, nor are they particularly user friendly.

In his PhD research, Wouter Verschoof-van der Vaart is therefore developing a universal artificial intelligence (AI) system that can find and classify archaeological objects on digital images. People who aren’t data scientists should also be able to use the system.

Your research has been running for two years. How far are you?

‘I’ve already identified an AI system that is very good at searching digital scans of areas: a Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (R-CNN). This model learns to search for objects on the basis of examples that you provide. The more examples you provide, the better the R-CNN becomes at finding objects.

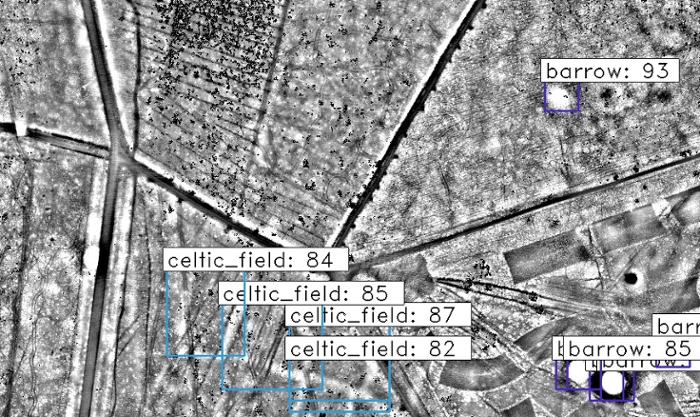

‘I’m now testing the system with LiDAR data – free elevation maps of the Netherlands that were produced by the Directorate-General for Public Works and Water Management. The R-CNN looks for three types of object on these images: burial mounds, prehistoric field systems and pits used to burn wood for charcoal. The results are very encouraging. The first version of the system detected 80% of our known burial mounds in the Veluwe and the second almost 90%. I’m going to spend the next two years refining the system. We’ve got LiDAR images from Germany, for instance, which one person has spent the last ten years studying. We’re now going to incorporate these into our dataset. We’ll then look at whether our network produces the same findings and how much faster our method is. Another aim for the future is that the network will be able to recognise other types of object, and in diverse areas.’

What is the benefit of a programme such as the Data Science Research Programme?

‘To begin with, the PhD candidates on the programme are using comparable methods, which means we can share problems and solutions with each other. For instance, relating to object recognition by AI systems. How do you make sure that an R-CNN recognises an object that is a slightly different shape or has a different orientation from normal? It’s also interesting for the computer scientists at the Leiden Centre of Data Science. They get to work with new types of data, such as in my case LiDAR data. What you need to do to this data before you can set an R-CNN loose on it is also of interest to them.’

Will data science enable us to find all archaeological objects in the Netherlands in the future?

‘A model can become better than people, but only to a certain extent, and like people, it will miss something every now and then. So I don’t think we’ll have found everything, but we will at least have found much more than now.’