A puzzle of sherds

Past objects offer a wealth of information about life in earlier times. Loe Jacobs is an expert in making earthenware objects, using the same methods and means used in earlier times.

If people had not started making pottery more than ten thousand years ago, our modern life would look very different. It is even debatable whether humans would have even been able to survive without pottery. Pottery made it possible to store food and drinks, and to cook.

Pottery sherds

Archaeological finds often consist of sherds. “Earthenware objects from archaeological contexts are usually fragile and vulnerable. Complete pots broke - and break - easily. Jacobs knows that the sherds will remain well-preserved in the ground because, due to their chemical composition, they suffer little further deterioration from moisture, acids and fungi. We can find out a lot from these sherds.”

Using sherds, Jacobs investigates how people have produced and used objects throughout the centuries - from the Neolithic to the Middle Ages. He is a global and much sought-after expert on the reproduction of ceramic objects. Through this experimental approach, he helps to answer questions about the production and use of such items. “It often begins with fitting sherds together to see the entire object as a complete entity. Once I have a good picture of the repertoire, I compare the earthenware objects to study the changes they have undergone.”

Tracing the history of production methods

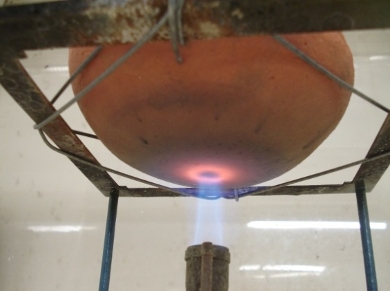

Changes during the production phase are usually due to changes in the method. Jacobs is searching for how and why a production technology changed. “Changes in the shape of a pot, for example, are usually not random, but are often the result of changes in raw materials, the firing process, or the erosion of the required skill,” Jacobs explains. Another explanation may be that competition arose from another source. “What matters is discovering the context of the different factors and thus forming a picture of the driving forces of human activity in the past. I do that by looking very fundamentally at how the pots were made.”

Trace analysis

Actions such as putting it down, stirring and cleaning cause scratches and shapes the wear on pottery. These use-wear traces provide information on how people used the objects, but it is also possible to discover what was cooked in them by analysing the cooked food or studying the ceramic wall damage that is an effect of certain fermentation processes. To avoid coming to false conclusions, scientists have to take into account traces that are the result of later corrosion. Although the material is highly resistant to weathering during its time in the ground, it may be affected under less favourable conditions. For example, by trampling, plant roots, salts or frost.

With his expertise, Jacobs contributes to international research such as the BEFIM project that studies drinking habits. Large numbers of drinking cups were excavated in France and Germany, along with other

Iron Age pottery, which indicates that feasting and drinking festivals were held in north-western Europe.

Had the elites adopted Greek and Etruscan feasting habits? Or did they give them their own meaning? Jacobs: “Intercultural influence is not something that is just common today but has gone on all throughout history. We try to determine details of this influence by analysing and interpreting traces of the pottery discovered.”

Cooking in ceramic

With his work, Jacobs not only helps large archaeological projects, but he also sometimes gains remarkable insights "in a smaller context". "For the last thirty years, I’ve learned a lot about ancient techniques, such as the hammer and anvil method in which pieces of clay are squeezed between two hard surfaces. This method works remarkably well for producing cooking pots: the products are incredibly strong and so can better withstand the thermal shocks inherent in cooking on open fires.” The method is being used more often these days now that the governments of some countries are encouraging the use of ceramics for cooking. Ceramics are very good for cooking stews because the heat distribution is much better compared to metal pots. The food is heated more evenly and is less likely to burn. Jacobs: "And a not altogether unimportant detail: people say it's much tastier."

Laboratory for Ceramics Studies

BEFIM – Bedeutungen und Funktionen mediterraner Importe im früheisenzeitlichen Mitteleuropa