Communicating about quantum: explanations improve understanding but reduce confidence

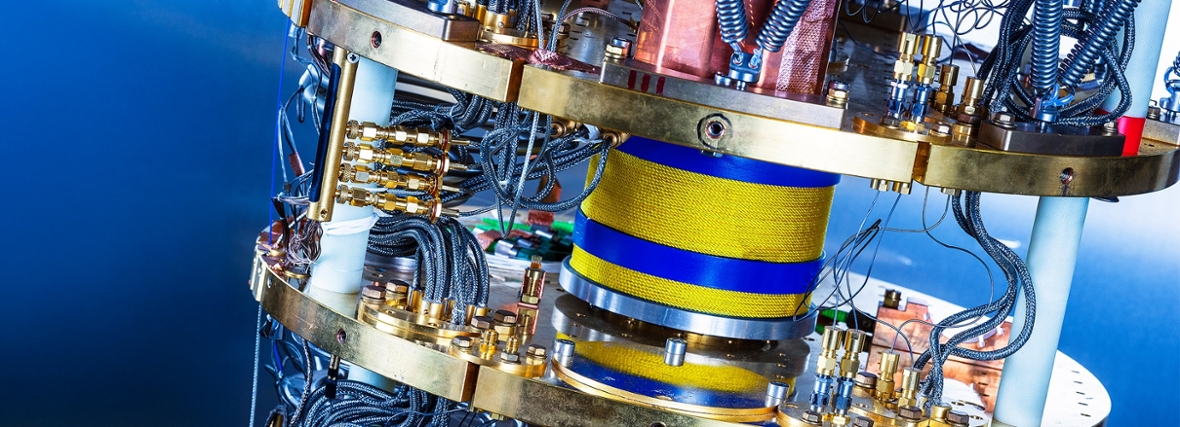

PhD defence image: Pim Rusch

Quantum technology has the potential to transform society. But how can you effectively inform the public about such complex and enigmatic science and technology? PhD candidate Aletta Meinsma explored this.

Over the coming decades, quantum technology will have a major impact on our lives. It could enable the development of new medicines and materials, and make ultra-precise measurements possible. But it also poses risks: current forms of digital security could become relatively easy to break, and criminals would be able to communicate beyond the reach of government. But two out of three people have heard little or nothing about quantum technology, Meinsma’s research shows.

Public engagement

This makes effective communication about quantum essential, says Meinsma. To build sufficient public support, citizens must be involved in the development of this technology. Only through public involvement can democratic participation be ensured in decisions on how quantum technology is used. A better understanding of the technology will also help people form a clearer picture of its potential impact on society.

What is quantum?

Quantum describes how the behaviour of the smallest building blocks in nature, such as atoms and electrons. At this scale, the laws of nature differ from those we experience in everyday life. For example, a particle can exist in multiple states at the same time until it is measured. Some particles can even remain connected across distance, a phenomenon known as entanglement.

These strange principles form the basis of quantum technology, such as quantum computers, sensors and communication systems. Quantum computers, for instance, can solve extremely complex problems, such as molecular simulations or logistical optimisation, far more quickly than classical computers.

The ‘mysterious’ frame

In the media, quantum technology is often described as ‘mysterious’ or ‘enigmatic’. Meinsma studied how this type of framing affects people’s understanding and engagement. ‘This frame was used in a quarter of the articles and videos that we studied. It was mainly used by experts, possibly to reassure the audience that it’s normal if you don’t understand everything straight away.’

Using this ‘spooky’ framing did not make people feel less engaged with quantum technology, nor did it reduce their understanding. ‘Mentioning this mysterious nature had no clear advantage or disadvantage,’ Meinsma notes. Nor did the use of metaphors affect people’s understanding or engagement.

Paradox of understanding

Meinsma discovered a surprising contradiction. Participants who received no explanation about quantum phenomena felt more confident that they understood the technology. By contrast, those who received an explanation felt less sure.

When their actual understanding was measured, however, the opposite proved true: participants who had received an explanation performed better than those who read the text without first receiving an explanation. ‘The explanation probably makes people aware of just how strange and complex quantum physics is. That makes them feel less confident that they understand the material,’ says Meinsma.

Communication advice

Based on her findings, Meinsma has clear advice for researchers, journalists and editors on communicating about quantum technology. One key recommendation is to broaden the focus beyond quantum computing and to pay more attention to other applications, such as quantum communication and quantum sensors. ‘Quantum computers may still take years, but quantum communication and sensors are already being used. They will affect our daily lives much sooner.’

Meinsma also observed that communication about quantum technology tends to emphasise the advantages, while paying less attention to the risks and drawbacks. Addressing these is essential if people are to reflect on the societal implications. ‘If criminals use quantum communication, governments may no longer be able to intercept their messages. In some scenarios, authorities could lose their grip on certain groups. By openly discussing these risks, we can help prevent unpleasant surprises.’

For more information about this PhD research, see Meinsma’s online magazine (in Dutch). Her PhD defence will also be streamed live on 28 January.