Partnering with businesses to scale up metabolism research

Predicting whether someone will fall ill and which treatment will benefit them most: that is the aim of the techniques that Professor of Analytical Biosciences Thomas Hankemeier and his research group are developing at Leiden University. In order to scale up and further develop this technology, he works with businesses. He also set up his own business, Mimetas, in 2013.

This is an article in a series about partnerships and impact on society.

‘We study the effect of the metabolism on cells and biological processes in the body,’ says Thomas Hankemeier. ‘One way that we do this is by studying the intermediate and end products of metabolism – metabolites as they are known – in bodily fluids such as blood and urine.’ Hankemeier has been a professor at Leiden since 2004 and has been Scientific Director of the Netherlands Metabolomics Centre since 2008.

Mini-organs

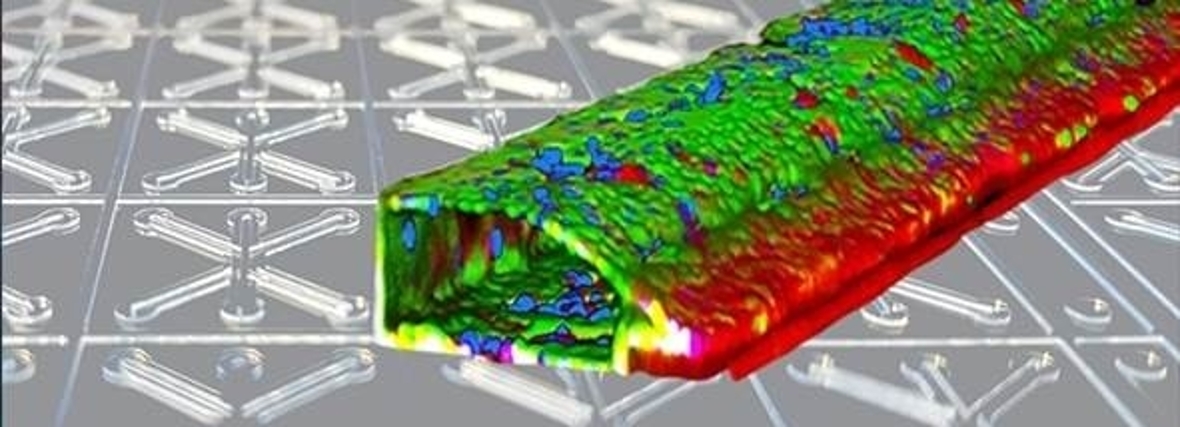

Hankemeier’s research group simulates human systems in the lab with organ-on-a-chip technology. This involves creating, at microscale, 3D blood vessels or mini-organs, such as brains or liver models. These models are more complex than cell models, which only grow in 2D. Blood vessels can run through organs-on-chips, and the cells of the organ are surrounded by other types of cell that usually play a supporting role in the organ. This makes an organ-on-a-chip a more realistic system.

‘We use organs-on-a-chip to simulate metabolites, for instance, that we find in the blood of certain patients as predictors of disease. We do this to discover their effect,’ says Hankemeier. ‘We then change the composition of the blood in the organ-on-a-chip to see how the organ responds. You can’t do such research in humans. You can’t just swap their blood and see what happens.’

New business

This research led to the launch, in 2013, of the first lab-on-a-chip company in the world, Mimetas. ‘I started the company with a good, entrepreneurial postdoc researcher, a PhD candidate and an external entrepreneur,’ says Hankemeier. Mimetas provides organ-on-a-chip technology for pharmaceutical companies, for instance, that use it to test drugs on 3D human tissue.

‘A university is an ideal environment for testing ideas and making discoveries,’ says Hankemeier. ‘But if a discovery is relevant to multiple industries or larger research areas, the work often no longer fits so well within the university setting. Then you can set up a business to scale up the technology or you can look for a company that wants to take the discovery to market and work together with them.’

Biobank

Hankemeier’s research group does a lot of work with businesses, food companies Danone and DSM for example. ‘They want to understand how nutrition can be used to treat or prevent disease, particularly now it is becoming increasingly clear what the role is of the microbiome – the useful bacteria that live in your gut – and that you can control this with food and probiotics, for instance. That research is in full swing.’

Hankemeier is also working with Imperial College London and a large English biobank on a plan to measure the metabolite profile in large numbers of blood and urine samples. ‘With such large-scale data, you can use the metabolites that are present to predict what the difference will be between people who develop dementia and people who contract another brain disorder, for instance,’ says Hankemeier. ‘This knowledge may help us treat diseases, or better still, prevent them.’