800 year old mystery of ancient bone disease solved

Scientific research at the molecular level on a collection of medieval skeletons from Norton Priory in Cheshire, United Kingdom, could help rewrite history after revealing they were affected by an unusual ancient form of the bone disorder, Paget’s disease. Osteoarchaeologist Carla Burrell, attached to the Leiden Faculty of Archaeology, is one of the project's researchers.

Chemical memory

The study involved analysing proteins and genetic material preserved in the bones and teeth that are more than 800 years old. The work suggests that ancient remains can hold a chemical memory of disease and that similar molecular analysis could be used to explore the evolution of other human disorders. The study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), is significant because it indicates that ancient Paget’s disease may have been far more common than the modern disease and developed much earlier in life.

Paget's disease

Paget’s disease is nowadays the second most common metabolic bone disorder and affects around 1% of the UK population over the age of 55, with an especially high prevalence in the North West of England. Both genetic and environmental factors are important in the disease, a likely explanation for the regional variations in its incidence. Paget’s disease can result in the weakening of the affected bone, causing deformity, pain, and sometimes fracture. In very rare cases, a bone affected by Paget’s disease can develop osteosarcoma, a malignant bone cancer.

Young adulthood

Dr Carla Burrell and Professor Silvia Gonzalez from Liverpool John Moores University, found that more than 15% of the skeletons at Norton Priory had extensive disease throughout up to 75% of their bones, compared to the modern day population with Paget’s disease who typically have just one or a few bones affected. The research also revealed that the medieval disease started in young adulthood, whereas nowadays Paget’s tends to develop after the age of 55.

Surprisingly though, the medieval cases showed almost no evidence of the complications that are common in modern day Paget’s disease.

William Dutton

One of the skeletons analysed was thought to be that of William Dutton, a medieval Canon at the Priory who died in the late 14th century. He was aged between 45 and 49 when he died and had bone disease affecting more than 75% of his skeleton, including pelvic osteosarcoma. Further analyses indicated he had a marine-based diet typical of a high status individual, and was local to the North West of England, pointing to some local environmental factor that may have triggered his disease.

Paleoproteomics

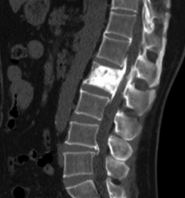

Coordinating the project, Professor Robert Layfield from the Nottingham Paget’s Association Centre of Excellence (PACE), said: “X-ray analyses of medieval skeletons from the collection at Norton Priory first directed us to unusually extensive pathological changes resembling, but also very different, to modern day Paget’s disease.'

The team carried out a much closer inspection of the remains using a technique called paleoproteomics – protein sequencing using mass spectrometry. 'This technique allows analysis of bone samples at the molecular level by extracting proteins from the ancient bone cells. Remarkably these proteins are well-preserved, whereas DNA degrades over extensive periods of time. Effectively the proteins offer an insight into the biology of the cell when it was alive many hundreds of years ago.'

Modern medical practise

Lynn Smith, Senior Keeper at Norton Priory Museum and Gardens said “the results of the scientific research into an ancient form of Paget’s here at Norton Priory has been a real surprise and is adding a huge amount to our knowledge and understanding of this unique medieval population. It is very rare for an archaeological collection to be used in such cutting-edge research and as such it has been both a privilege and a career highlight for me. The results will not only help re-work our interpretation of the site and the individuals that had connections with the Priory but will also help inform modern medical practise and future research”.

Ancient environmental triggers

The next stage of the research will be to determine what the ancient environmental triggers for Paget’s disease might have been, which may help doctors understand the fall in incidence of modern day disease observed over the past few decades. By further applying the methods developed in the project the reserchers also hope to to gain a better understanding of what daily life was like for our ancestors affected by this, and other, ancient bone disorders.