Indigenous people as essential research partners

The knowledge held by indigenous people is essential if you want to study the history or the language of a particular region. Leiden archaeologists and linguists are now looking for ways of involving local people more systematically in their research.

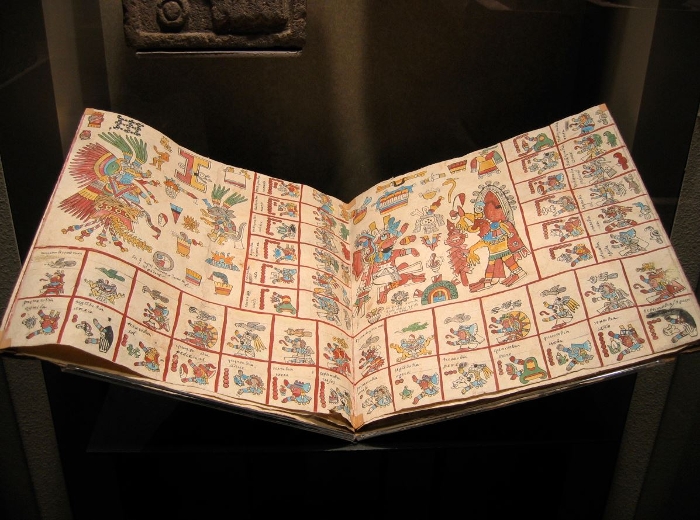

Imagine you are researching the centuries-old pictorial writing of the Mixtecs, or you are studying the language of the present-day Maya population on the Mexican peninsula of Yucatan. You can, of course, as a Leiden researcher go to Meso-America to examine archaeological finds or study the local languages. But you can also opt to conduct this research together with the native people.

This last option is what Leiden archaeologists and linguists are aiming for. They have recently come together in the Centre for Indigenous American Studies (CIAS), a virtual centre for research on the indigenous peoples of Latin America. The aim of CIS is to give indigenous people a bigger say in academic research on their native region.

Western reference framework

‘It is important to involve present-day native people if you want to have a real understanding of the language and culture of a region,' Maarten Jansen, Professor of Heritage and Indigenous People, comments. 'Take, for example, the study of a Mixtec codex, a pictorial script that for non-experts looks something like a comic strip. It is difficult for a Leiden researcher to gauge the value of particular symbols or gestures in the images, because you are looking at them from a Western reference framework. But if you involve the 500,000 or so Mexicans who still speak Mixtec, a new world will open up before you.’

Jansen has seen this many times over the course of his long career, whenever he discussed his research in small Mixtec villages. The codices are part of the local identity, the centuries-old oral traditions. It was only with continuous input from the descendants of the ancient Mixtecs that Jansen was able to become a specialist himself on the native pictorial languages. It enabled him to publish elaborate studies on just about every important codex.

Sustainable Humanities

The Faculties of Archaeology and Humanities are now trying to anchor Jansen's way of working in all their research on indigenous populations. With funding from the Dutch government's Sustainable Humanities programme, two university lecturers and two PhD candidates have now been appointed to coordinate this interdisciplinary collaboration, alongside their research. Three of them are themselves from indigenous communities in Mexico and Guyana.

According to Eithne Carlin, they have a further aim: to decolonise archaeology and linguistics in Leiden. Carlin is conducting research on the languages of the Guyanese people, in particular the Caribbean and Arawak language families. She believes that having native people take part in the research is not only useful for gathering academic knowledge, but is also as a way of reducing global inequality in science. 'At the present time, Western science is in a privileged position, which isn't always the way it should be. We can reduce that privilege by involving more native researchers in our research and recognising the value of their knowledge.'

Building support

‘All too often I see researchers going to an indigenous community to carry out research there, without really thinking in advance about the ethic aspects that are likely to play a role,' comments Genner Llanes Ortiz. He is himself a Maya anthropologist from Yucatan, and he is one of the four researchers who have been brough to Leiden within the framework of CIAS. ‘In the coming period I will advise archaeologists and linguists - but also anthropologists and biologists - on how they can carry out their work in a respectful way. It is particularly important that they don't rush in, but that they first build support within the local community. It's their history and their identity, after all.'

According to Llanes Ortiz, land, spirituality, language and self-determination are fundamental components of indigenous heritage. Ideally you should make sure you involve the local inhabitants whenever you are researching one of these aspects of their culture. 'The best way of doing that is by making indigenous interests an integral part of your data collection and analysis. Sharing the research findings with the local population can also make them more likely to look positively at the research and to take part in it. And that can also be a benefit in protecting indigenous heritage.'

Connecting with existing contacts

Llanes Ortiz recently visited Mexico with a delegation from Leiden University to strengthen the relations with research institutions there (see box). Niels Schiller, scientific director of the Institute for Linguistics (LUCL), was a member of the delegation. He and his colleagues are eager to chart and describe the many languages of Meso-America. Western knowledge of language processing is largely based on the study of around ten mainly Western (Indo-European) languages. Knowledge of language processing among speakers of non-Western languages is essential to test these Western assumptions.

At the same time Schiller is also aware of the ethical challenges involved. His colleagues take with them lightweight equipment with which they can make measurements 'in the field' of eye movements, and shortly this will even include brain activity - two important indicators for language processing. Schiller: ‘But we don't want to harass the local population. You don't want to create a setting in which Western researchers use local people as guinea pigs for their research. To avoid that, I made agreements with CIESAS, an institute for social sciences, that Leiden researchers can have access to speakers of native languages. It's always better to connect with existing contacts.'

Ultimately, this kind of collaboration benefits both science and the local population, Jansen believes. 'On the one hand the native people are helping us unravel scientific mysteries, and on the other hand this shared effort generates more insight into the history and identity of the relevant population. It's a win-win situation.’

Broadening the collaboration with Mexico

This article was written following a recent visit to Mexico by a delegation from Leiden University. While in Mexico, Rector Magnificus Carel Stolker signed a number of partnership agreements with Mexican universities and research funding agencies.