Endangered worldviews and heritage

Indigenous Peoples possess unique perspectives of the world that will be lost if their knowledge and heritage are not documented, studied and protected. If we lose this knowledge, we are losing part of our own heritage.

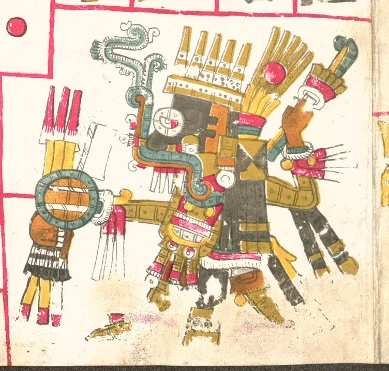

Pictorial writing on deerskin

Professor Maarten Jansen investigates ancient pictorial writing systems from pre-colonial Mexico. He deciphers these images and tries to uncover the meaning of the accompanying stories and descriptions. In this way, we can find out more about Indigenous Peoples and preserve their heritage. These pictorial writing systems are books made of broad strips of deerskin. Jansen: ‘All pre-colonial books, with the exception of half a book, can be found in European collections. They were brought to Europe starting from the 16th century. They represent the languages, memories and worldviews of the people who created them.’ Jansen works together with native people who still speak these languages (Mixtec, Maya, Aztec) to try to understand these books. The number of native speakers alive today depends on the language, and figures vary greatly. ‘There are sixty different languages in Mexico. Approximately 2 million people speak Aztec. For other languages, the number of native speakers varies from half a million to merely a handful of elderly people.’

Balance between people and nature

‘Every year on 3 May, indigenous communities move to the caves – the rain god Tlaloc is said to live in a cave – and pray for rain. The books I study contain many similar ways to invoke the God of Rain: these ways are very ancient. I was able to transmit the incantations and customs from these ancient books to local communities. This is very important to them, because these communities continue to be inspired by ancient worldviews and ethics. Their worldview is about the balance between people and nature, and they believe that people should not try to control nature, but rather serve it.’ This worldview also leads to serious conflicts between ‘indigenous’ and Western perspectives, explains Jansen. ‘Whereas the West sees nature primarily as a source of raw materials and as something to be used, the indigenous perspective sees humans as subordinate to nature. This perspective, this heritage, should at the very least be included in our global discussion on Indigenous Peoples.’

The forest as a worldview

Linguist Eithne Carlin, who studies the languages of the peoples of the Amazon, notes that when a language disappears, unique worldviews also disappear. She documents and describes indigenous languages because language, the repository par excellence of knowledge of the world, is also one of the most powerful symbols of one’s identity. In the case of Indigenous Peoples that core identity has been attacked, eradicated or eroded by the colonial past and present. When indigenous languages cease to be spoken, we lose a window into the nature and structure of knowledge which may be radically different from but complementary to western knowledge paradigms. ‘One of the challenges we are facing in this context is that Western languages lack the words or categories for expressing the worldview of Indigenous Peoples. For example, Cariban languages have eleven ways of saying ‘in’, depending on where an object is located: in an open field, in a house, or in the forest. House and forest are both viewed as containers. This is due to how the people in this area perceive their environment. Imagine: when you live in a forest, you live in a kind of well. You don’t see the horizon, and you have a very limited view of your environment. But what you do see is a lot of detail. Every single variation of the leaves on fifty different trees. It’s a completely different way of life. And its wisdom is embodied in the languages.’