How does the European Union tackle disinformation? ‘Much more than a security issue’

Interview met Sophie Vériter

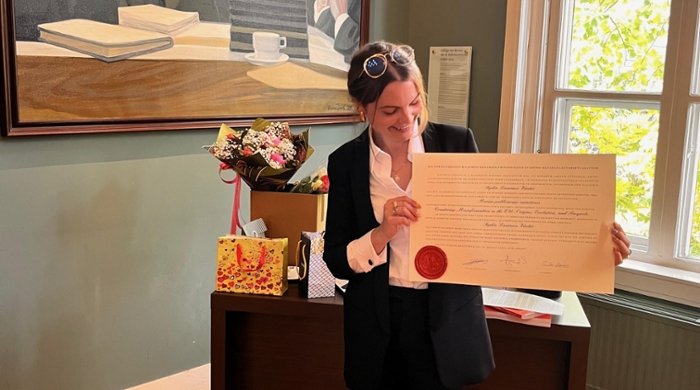

During her work for the European Union, Sophie Vériter witnessed how young people in countries like Ukraine and Moldova were exposed to Russian propaganda. After mapping out the EU’s disinformation policy, the PhD candidate now advocates for a revised approach.

What is your background?

‘I was born in Brussels and have lived and studied in both Belgium and Spain. The two years before I moved here, I studied in Oxford, which was a fantastic experience, but I wanted to pursue a PhD in an environment where I could do more than just theoretical research. Here in The Hague, everything is within reach, with Brussels just around the corner. This allowed me to conduct many interviews with government officials. For me, it was the perfect place to do what I wanted to do.’

Why did you choose this topic?

‘After completing my bachelor’s degree in Brussels in 2016, I worked for the EU for two years as a communications adviser in the field of public diplomacy. I helped to create a campaign for Armenia, Azerbaijan, Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, and Georgia. I communicated about the EU to young people in those countries, built a network, organised events and school visits, and more. In this role, I became familiar with issues such as propaganda and information manipulation, as these countries are caught between Russia and the EU and were bombarded with conflicting messages. I noticed that some of the narratives made no sense or were being heavily pushed.’

Do you have an example of this?

‘I saw videos containing Russian propaganda and entirely false information — for instance, that the EU had failed to honour previous agreements with Russia that justified its war in Ukraine. The narrative in Russian media is very different from that in Western media. After the Charlie Hebdo attack in 2015, Russian media claimed the victims had brought it on themselves — that they had gone too far in their freedom of expression and therefore deserved it. In Western media, it was seen as a tragedy and an attack on free speech. In Russia, the media is not as independent as it is in the Netherlands — they cannot be too critical of the Russian government or its narrative.’

Russia spends 29 million euros per week on strategic communication, while the EU spends less than one million

So that’s where it started for you?

‘Yes, because that’s when I became aware of competing narratives, and I was part of the response to them. In comparison to Russia, we were hardly doing anything. Their budget for strategic communication is 29 million euros per week. The EU budget has doubled in recent years to 44 million in 2025 – which amounts to less than one million per week – a fraction of the Russian budget. A new EU unit was set up to counter this kind of propaganda. I wondered: why didn’t we do this earlier?’

Can you explain why?

‘I interviewed around fifty EU officials, diplomats and representatives working in Brussels. The annexation of Crimea had taken place, and there was a growing awareness of what information manipulation could lead to. A group of countries considered the creation of this unit essential — particularly the Baltic states, which have large Russian-speaking populations and feel their security is at stake. Denmark and the United Kingdom were also involved. Latvia took the first step and seized the opportunity when it held the presidency of the Council of the EU. I found it fascinating that such a small country could have such a major impact. Since then, I’ve been following this policy field.’

How did the policy develop after that?

‘It progressed very rapidly. New teams were set up to focus on other regions such as China and the Balkans. After the COVID pandemic, it became clear that disinformation also had a major impact in other areas. This led to legislation like the Digital Services Act (DSA), which requires digital platforms to be more transparent about their algorithms and to take measures against harmful content and disinformation, even when it’s not strictly illegal.’

What impact has the war in Ukraine had on this policy?

‘EU policy accelerated significantly. In 2022, the EU took a rare step by banning Russian state media outlets like Sputnik and RT. Such bans are uncommon in the EU, but in times of crisis, exceptional measures can be introduced. It’s now obvious that Russia aims to manipulate, and we’ve become more aware of the techniques — bot farms, large-scale operations designed to spread confusion and division via social media.’

'It is now abundantly clear that Russia wants to manipulate.'

Is the EU now tackling disinformation effectively?

‘It’s clear that not everything is working perfectly. The EU’s response to disinformation began with countering Russian propaganda. Now the response is much broader, involving algorithmic transparency, platform regulation, and enhanced communication — a wide-ranging toolkit. Initially, the focus was mainly on security. Now, disinformation is increasingly seen as a threat to democracy. With security policy, all EU member states must agree. That makes decision-making difficult — but when agreement is reached, it yields more power. Still, I believe it’s problematic to view disinformation solely as a security issue.’

Why is that?

‘Because it reduces public involvement in the debate. Citizens are sometimes asked for input on budgets or social policy, but when it comes to foreign and security policy, the public is left out of decision-making. Currently, you vote every few years, but there’s little room to engage in the process. Especially with disinformation, there’s hardly any democratic input, because it’s framed as a security issue. That disconnect between the public and its governing elite undermines trust.’

So it shouldn’t be considered a security issue?

‘It’s much more than that. My interviews showed that framing it as a security issue can make it easier for governments to act — but without transparency. The meeting notes are not made public. That increases the gap between citizens and institutions. And the measures are not particularly effective either — fact-checking alone doesn’t work. It’s better to invest in long-term strategies: media literacy, support for quality journalism, and critical thinking from an early age. In Finland, children learn in primary school how to assess the news and verify sources. You have to be proactive: prevention is better than reacting afterwards.’

Links

-

Also read an article in which Sophie explains how EU policy on disinformation has developed and why a democratic approach is important.

-

Sophie has compiled a toolkit with a bibliography of key academic references on strategic communication, propaganda, and influence.

Sophie gave a short speech at her PhD defence ceremony on 3 June – read it back.