Jan Hendrik Oort: world-famous yet unassuming astronomer

He discovered how to determine the rotation and centre of our Milky Way, predicted where comets come from and laid the groundwork for radio astronomy: Leiden Professor of Astronomy Jan Hendrik Oort (1900 – 1992). Piet van der Kruit, whose PhD supervisor was Oort himself, has written a biography about this ‘master of the galactic system.’ ‘He was one of the greatest scientists of the 20th century.’

Piet van der Kruit doesn’t beat about the bush: it was high time for a biography of Jan Hendrik Oort. This retired Groningen Professor of Astronomy calls Oort one of the greats of astronomy. ‘He put astronomy in Leiden on the map and was one of the greatest scientists of the 20th century. Oort was the Einstein of astronomy.’ Oort’s most famous discoveries are the Oort cloud – where comets come from – and the Oort constants. The formulae for these constants, which Oort used to determine the centre of the Milky Way and the rotation of our galaxy, grace the wall of a house on Witte Singel in Leiden that is opposite the Leiden Observatory, where Oort spent so many years working as a researcher, professor and director.

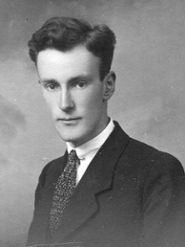

Jan Hendrik Oort was born in Franeker on 28 April 1900, the second son of psychiatrist Abraham Oort and his wife Ruth. The family moved to Oegstgeest when Abraham was made head physician of Rhijngeest Sanatorium and took up residence in the director’s house. This is where Oort’s younger brother and two sisters were born.

Exemplary student

Oort spent his youth in Oegstgeest and Leiden, where he went to primary and secondary school. He went to university in Groningen when he was 17. He was unsure whether to study physics or astronomy. Famous astronomy professor Jacobus Kapteyn taught in Groningen, one of the main reasons why Oort wanted to study there. Although he also admitted that he didn’t fancy the competition with his brother Hein, who was studying physics in Leiden. That he had always had a good relationship with his brother is clear from a letter that he sent him during his first weeks in Groningen. He drew a plan of his room and wrote: ‘... it’s gradually beginning to feel like my room, now I’ve got my own books and have my photos hanging on the wall. I’ve made a drawing, so that you can imagine how fine it would be if we were to sit here together when you came to visit.’ Sadly, Hein died of diabetes in June 1922 – just a few months after the discovery of insuline

![A letter from Oort to his brother Hein, with a sketch and description of his room in Groningen. ‘[...] so that you can imagine how fine it would be if we were to sit together here when you came to visit,’ he writes to his brother. (Photo: Oort Archives)](/binaries/content/gallery/ul2/main-images/general/afbeeldingen-in-tekst/190923-biografie-oort/biografie-jh-oort-copyright-3.jpg/biografie-jh-oort-copyright-3.jpg/d700xvar)

His decision to study in Groningen, and in particular under Kapteyn, proved to be the right one. Oort found Kapteyn’s lectures gripping and decided that he would definitely to study astronomy. He was an exemplary student and was awarded his Doctoraal (Master’s degree) with the cum laude honour. During his studies, his work had already caught the attention of Kapteyn, who told his colleague at the Leiden Observatory, Willem de Sitter, that there was a clever upcoming astronomer.

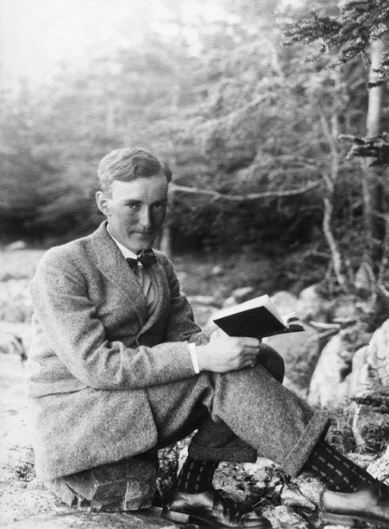

Practising observations in the United States

After graduating, Oort began work as a research assistant in Groningen, under Pieter van Rijn – who had succeeded the late Kapteyn as professor. But De Sitter wanted to bring Oort to Leiden. Oort also liked the idea of returning to his home town. However, said De Sitter, this was on the condition that Oort gained experience abroad of astrometry: measuring the positions and movements of celestial bodies with telescopic observations. After his brother’s death in 1922, Oort left for the United States. He worked at Yale Observatory for two years, where he became very proficient in making observations with telescopes.

Return to Leiden

Before Oort left for the US, it had been agreed that he would come and work at the Leiden Observatory. His professor in Yale wanted to keep him longer than the two years, but De Sitter told him that if he didn’t return, the job would go to someone else. So Oort became director of the Department of ‘Positional Astrometry’ in Leiden in 1924. Interesting detail: De Sitter had first set his sights on astronomer Anton Pannenkoek. But Pannenkoek was a communist and the Minster-President refused to grant permission for his appointment in Leiden, which was necessary because Leiden was a rijksuniversiteit, a university of the kingdom of the Netherlands.

Oort constants

Oort received his doctorate at the University of Groningen in 1926. The title of his dissertation was The Stars of High Velocity. He continued his research into high-velocity stars in Leiden, and proved Bertil Lindblad’s theory that our Milky Way isn’t motionless but rotates instead. He then showed that this is a differential rotation: the rotational velocity of the stars and the centre of the Milky Way depend on their distance from the centre and the velocity decreases towards the outside. The formula that Oort uses to describe this rotation contains two constants known as the Oort constants.

In 1935, he was made a professor in Leiden and moved with his family to the house on Sterrewachtlaan 5. He kept a low profile during the Second World War, working from a house in the Veluwe area, but he did join Kleine Krans, a resistance group of professors against the occupier’s interference in the University’s research. After the war, as well as professor, Oort became director of the Observatory, and returned with his family to the house alongside the Observatory.

Godfather of radio astronomy

Technological developments had taken flight during the war, also in astronomy. Oort directed his attention to radio astronomy: using radio waves to chart the universe. He established the ‘Radio Waves of Sun and Milky Way Foundation,’ a partnership between the Leiden and Utrecht observatories, the PTT and Philips. Oort was good at bringing together different parties; he was insistent that radio astronomy was of great importance and required cooperation. As a result, the parties conducted joint research from ‘Radio Kootwijk’: an old radio antenna belonging to the Germans that had fallen into disuse after the war. He also raised funds for the construction of a new radio telescope in Dwingeloo in the Netherlands. This was officially opened by Oort together with Queen Juliana and Minister-President Jo Cals in 1956, and in 1970, in part through Oort’s efforts, the large telescope array opened in Westerbork. This radio telescope is still in use, and Oort is seen as the godfather of Dutch radio astronomy.

Where comets come from

The other major discovery for which Oort is famous, the Oort cloud, was more of a chance discovery. After the war, Oort became the supervisor of PhD candidate Adriaan van Woerkom because his supervisor Woltjer had died as a result of the Dutch famine. In his dissertation, Van Woerkom, who conducted research into comets, disproved various theories about their origins. Oort developed an explanation of why new comets are always appearing – comets vaporise after a few laps of our solar system, so ‘new’ ones must come from somewhere. According to Oort that was a large cloud in the outer reaches of our solar system that is full of comet-like objects from the origins of our solar system: the Oort cloud. As this cloud centres around the sun, comets can continue to pop up in all corners of our sky.

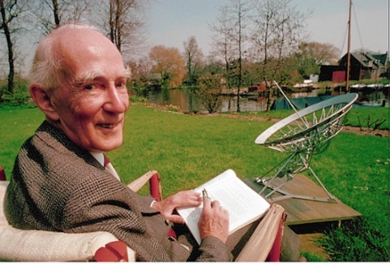

Oort garnered world fame as an astronomer, not only for his discoveries but also for his efforts to bring together parties within the discipline, radio astronomy, for instance. Oort was also at the cradle of the ESO, the European Southern Observatory. He brought together six European countries to realise an observatory in Chile – and thus not lose the ‘battle’ with American astronomers. As Oort’s fame grew, so too did the reputation of the Leiden Observatory: researchers from all around the world came and still do come to Leiden for its astronomy. The Leiden Observatory, now no longer housed in the historical building on Singel, is still one of the largest and most renowned institutes of astronomy in the world.

Leiden legacy

Oort retired in 1970, but he couldn’t turn his back on astronomical. His former colleague Harry van der Laan remembers Oort saying the following when he left: ‘Astronomy was so boring before 1950. Now it’s becoming truly exciting.’ And an Oort could still be seen in the corridors of the Observatory: grandson Marc also decided to study astronomy and spent some time working as an astronomer in Leiden. Although they didn’t work together on the same topics, Marc and his grandfather shared an office in Leiden for a few months [see below].

When Jan Hendrik Oort died in 1992, astronomy lost a great scientist. Physicist Subramanyan Chandrasekha said the following: ‘The great oak of astronomy has fallen, and we are lost without its shadow.’ Biographer Piet van der Kruit agrees: ‘Oort meant so much for astronomy, in Leiden, in the Netherlands and all around the world.’ His legacy is apparent in Leiden, with the Oort constants gracing a wall, the Jan Hendrik Oort Bridge in Oegstgeest and the Oort Lecture that is held each year at the Observatory.

Hendrik Jan Oort: Master of the Galactic System

It took Piet van der Kruit three years to write Jan Hendrik Oort’s biography. Oort was once the PhD supervisor of this professor emeritus of Astronomy in Groningen. ‘I knew him personally, so what I came across in his archives didn’t surprise me. But I think that a lot of people will be dumbfounded by how many observations he continued to make. He was known as a theoretician in astronomy, but observations were extremely important to him as well. And his tenacity was sometimes confused with arrogance – I think that this biography also shows that that impression is wrong. It was more that he was reticent or shy in personal contact.’

The first copies of the biography were presented to grandson Marc Oort and Ewine van Dishoeck, Leiden Professor of Astrophysics and one of today’s big names in astronomy, at the Leiden Observatory on 29 August. Van Dishoeck remembered meeting Oort when she was still a young researcher. ‘Oort said he was jealous of me because I was going to discover so many wonderful things.’ Grandson Marc also shared some memories of his grandfather at the presentation. ‘As the family of a famous person, you never understand why people would want their biography. What was so special about grandad?’ He also spoke about how he was ten when he decided to study astronomy. ‘There was a simple reason for this: I wanted to live at Sterrewachtlaan 5, my grandparents’ house, because you could ride your scooter through the house.’ Marc later became fascinated by his grandfather’s radio maps, which were spread out over the table-tennis table. That was what decided it for him. He is full of praise for the biography, which he had already proofread: ‘It is a fantastic book with a good balance between science and personal anecdotes by and about my grandfather.’

The scholarly edition of the biography ‘Jan Hendrik Oort – Master of the Galactic System’ is available as an e-book and inhardcover from Springer Publishers. A public edition will be published by Prometheus Publishers in January 2020, titeld ‘Horizons: a biography of astronomer Jan Hendrik Oort’.

Text: Marieke Epping

Photos: all rights reserved

Mail the editors