A small ode to 412 dead

In 2011 Leiden University came into possession of the skeletons from a graveyard in Middenbeemster. But what could be done with all these bones and skulls? Well, the answer is: more than you might think. Since the excavation, it has been raining interesting scientific discoveries at the Faculty of Archaeology. ‘This collection just keeps on turning up new findings.'

Sara (66) lies stretched out on a triple layer of bubble plastic on one of the work benches at the Faculty of Archaeology - or at least her bones do. She died in 1863, and her cleaned and polished bones are all that remain of her. Archaeologist Rachel Schats had arranged the skeleton in perfect order, from the shin bone to the femur and from the vertebrae to the skull.

Sara lies there, stretched to her full length. But, if you were to climb onto the work bench and lie next to her on that bubble plastic, it would immediately be obvious that there is something not quite right. The woman suffered from dwarfism, and probably never stood taller than the chest of her adult contemporaries. In around 1850 she could be seen walking arond Middenbeemster, just 1.30 metres tall.

‘It's a remarkably interesting find,’ Schats comments. ‘We have found Sara in archive documents, which have given us some interesting details about her. She lived to a very old age. And even more surprising: she married and had rather a lot of children. Everything points to her having been a respected member of the community. In spite of her physical handicap, she played a full part in her community. That's somethng I wouldn't have expected in a farming community 150 years ago.'

Excavating is something you can learn

Sara is just one of the 412 skeletons excavated in Middenbeemster in 2011. When the Protestant church wanted to build an annex, the graveyard had to be cleared. That's not so unusual: in the over-full Netherlands, being laid to rest for eternity is an illusion. Old graves have to make way for new ones, and there are times when a complete graveyard has to be cleared. Sometimes Leiden University is given the opportunity to excavate the skeletons for scientific research. ‘In Middenbeemster it was either us or the mechanical digger,'Shaats says. 'And that makes us the more pleasant option.'

Visitors to Middenbeemster in 2011 would have seen the students at work among the graves. They were busy with their shovels and trowels removing the soil layer by layer to reveal the coffins and their skeletons. Paintbrushes and vacuums were used to remove the final remnants of sediment with the utmost care. 'Middenbeemster isn't only of scientific value for us,' Professor Menno Hoogland who led the excavation explains. 'Dozens of Leiden's archaeology students have also learned the finer points of excavation techniques here.'

Ultimately 412 skeletons were brought to the surface, all of which were buried between 1829 and 1868. Hoogland, Schats and other colleagues succeeded in identifying 120 of them. It was initially a difficult process but then one of the long-deceased Beemster inhabitants offered a solution. This man, Dirk Olij (see the box), had had the lid of his coffin decorated with small metal nails. D.S. Oly, died 2 March A. 1833, 79 years old, was hammered nail by nail in the lid of the coffin. This was the first instance where a grave could be linked to a particular name. Thanks to this discovery, the archaeologists were able to decipher an old layout of the graveyard.

‘The Historical Association of Middenbeemster was an enormous help here,' Hoogland says. Around 400 of the 8,000 residents of Middenbeemster are members of the association, which is a remarkably high percentage. 'They helped us in the first instance with cleaning the bones, and later they did an enourmous amount of work in the Waterlands archive. And even today - eight years after the excavation - they spend two days a month in the archive. And the most amazing information is still coming to light.'

Superb workmanship

Back in the lab at the Faculty of Archaeology Rachel Schats points to the next spectacular find: a skull with a very well maintained set of teeth and enamel that simply gleams with good health. Who would have expected that at a time when toothpaste didn't exist and oral hygiene was in the hands of a none-too kindly surgeon? It seems too good to be true, and that's just what it is. Because... the skeleton is wearing false teeth.

‘I can't remember ever having seen anything like this; it really is a marvellous set of teeth,' Schats says while handing the dentures. She did not examine the teeth herself, but is familiar with the scientific article written by her colleagues. ‘The prosthetic is made of silver and the teeth are even more ingenious; they are made of porcelain, overlaid with a thin layer of glass. You can see from the wear that the dentures were worn for a long time. There's no way they would have been comfortable to wear, but it is a superb piece of workmanship.'

Large-scale analyses

As well as these kinds of pearls, the Middenmeemster collection is highly valuable because of the large number of 'normal' skeletons. All that bone material has been well preserved, dated and in many cases even identified. This means it is possible to carry out large-scale analyses, for example to gain an image of the illnesses that were common in North Holland at that time. And by comparing these data with other excavations in the Netherlands and abroad you can make some amazing comparisons in place and time.

‘My colleague Barbara Veselka, for example, compared skeletons from different graveyards at home and abroad to see if they showed evidence of a lack of vitamin D,' Schats explained, turning over the femur of a young Beemster resident. 'A shortage of vitamin D causes problems with bone mineralisation, which can lead to all kinds of unpleasant complications, such as the legs becoming bowed as a result of the person's weight. You can see that with this bone: it is very thick and the lower part of the bone is porous at the end. The lack of vitamin D has really stunted the natural growth of the bone.'

Initially, this 'English disease' was thought to occur mainly in grey cities during the industrial revolution. Veselka's research shows that the farming people in old Middenbeemster had roughly the same lack of vitamin D as the city dwellers. It could well be that the people of Beemster in those days received no sun on their skin because of their long, traditional dress, and as a result their bodies did not produce enough vitamins. In any event, we now know that the English disease was not as typically British as the name suggests.

The tragedy of a graveyard

Research by another colleague mentioned previously – Andrea Waters-Rist – showed that babies in Middenbeemster were breast fed for a only remarkably short time after the birth. She discovered this based on what are known as nitrogen isotopes in the bones, particles that are at their peak in infants. Compared to other infants, small children in the Beemster area moved on to other kinds of food, probably cow's milk, at an early stage. This may indicate that women in Middenbeemster had many children in quick succession.

‘A graveyard like this brings together in one place all the tragedies and the poverty of the rural areas in the nineteenth century,' Hoogland says. 'Sometimes you come across, for example, three or four chldren in the same grave, all of whom had the same name. The family was so keen to have a John, but each time a baby was born it died soon after birth. There are also graves where the mother is lying beside her new-born child, both having died in childbirth.'

Eight years after the excavation, around 15 students still graduate every year based on an in-depth analysis of some aspect of the Middenbeemster collection. In addition, a collection of Arnhem skeletons will soon be added to the collection, which means there will be even more to investigate and compare. The only problem is the lack of storage space,' sighs Schats. Building management is beginning to complain that all these skeletons take up too much space. She thinks for a moment, and then says resolutely: 'But the Middenbeemster collection is simply too good to put away, it will never retire'.

Text: Merijn van Nuland

Mail the editors

‘It struck me like a bolt of lightning: we are family’

Annelies Kleindieck-Olij is a distant relation of Dirk Olij, the man who, thanks to the inscription on the lid of his coffin, made a crucial contribution to the unravelling of the history of the graveyard in Middenbeemster. These excavations have provided her with a lot of interesting information about her ancestor.

'When I heard that a Dirk Olij had been dug up, I was told by several fellow villagers: "Hey, that's your maiden name." Without too many expectations, I went with my twin sister to the presentation made by the archaeologists atLeiden University and the people of the Middenbeemster Historical Society . I actually walked into that church completely blank.

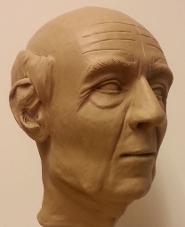

'But then they showed the facial reconstruction of Dirk Olij. My mouth literally fell open with amazement. It struck me like a bolt of lightning: we are family. He had so many of my father's features. My twin sister felt the same way. The contours and the expression of the face, the high forehead, the position of the eyes, the cheekbones... It was also something of a confrontation, because my father died ten years ago. And now it was suddenly as if he was standing in front of me again.

‘A few days later, when I went to do my voluntary work at the tourist office, I was shocked to see the bust of Dirk Olij in the reception room! Apparently they were going to give him a place there. The Historical Society has now moved the statue to the Heritage Room, right next to the tourist office. But if anyone is interested, I am happy to show him to them - and to tell them proudly that this man is an ancestor of mine.'