Catholics in the Dutch Republic were creative directors of their own lives

The Catholics were by no means pitiable victims over the two centuries that they had to practise their religion underground, Caroline Lenarduzzi writes in her PhD dissertation. They managed to keep their faith alive from the mid-sixteenth to the mid-eighteenth century. PhD defence 25 October.

From around 1580, anti-Catholic decrees came thick and fast in the Northern Netherlands: all forms of Catholic expressions were forbidden on pain of fines, imprisonment or exile. How did this development come about?

'Beggars'

The cause can be traced back to the Eighty Years War. The 'Beggars', impoverished nobles along with vagrants and criminals who, from 1560, formed organised groups, were strongly anti-Spanish and anti-Catholic. They were far from subtle fighters and cared little about whether there was one Catholic more or less. But at the same time they were the strongest army that William of Orange had to fight the Spanish. The reputation of the Beggars was seriously damaged by their torture and murder of twenty Catholic priests in Gorkum ('the Gorkum martyrs'). As a result, many cities only allowed them to enter on the condition that they left the Catholics in peace.

More paths to Rome

Carolina Lenarduzzi used ego documents to study how individual Catholics in the Northern Netherlands who did remain revised their traditional practices and rituals. How did they regard their religious identity? What did they think differentiated them from non-Catholics? By following three strict Catholics and their families, Lenarduzzi learned that there were different ways of adapting to the new reality. For some, protecting their social status was the most important concern. They were prepared to make so many concessions that their fellow Catholics no longer regarded them as Catholics, although they themselves thought differently about this. And even for the most die-hard Catholics, their loyalty was not always to their religion. What is remarkable is that none of the Catholics that Lenarduzzi studied renounced the last sacrament when they were dying. Maybe they still regarded it as a 'ticket to Heaven'?

Ban on practising Catholicism in public

But things worked out differently. Hundreds of Catholic regents in the cities did not trust the situation and they left, to be replaced by Calvinists. This created an anti-Catholic atmosphere, which was rapidly confirmed by a ban on practising Catholicism in public, in any way whatsoever. Priests were no longer allowed to celebrate masses, churches and monasteries were handed over to the Calvinists or secularised, and property belonging to the Catholic Church was confiscated

Good patriots

There is no question that Catholics wanted to give meaning to the traumatic period in which they found themselves. One of the ways they did this was by preserving iconic memories of the Catholic past and handing them down to future generations. These memories also inspired Catholics to become activists, anticipating the possibility that they might one day be able to practise their faith openly again. In this light, the past fed the present. At the same time, local memory cultures show that Catholics' religious identity and their identity as inhabitants of the city competed with each other; even the strictest Catholics tried to find a harmonious balance between the two loyalties and restore the relationship with the city. Moreover, when the Republic was threatened, as in 1672, when the French invaded the Republic, some Catholics portrayed themselves as 'good patriots': they put the Reformed Republic above Catholic France.

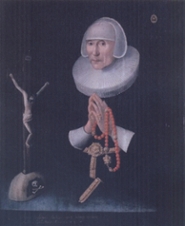

Catholics cultivated what the Calvinists condemned

Lenarduzzi observes that all Catholics preferred to cultivate those parts of the Catholic code of conduct that the Calvinists fiercely opposed and condemned, including the material and musical culture of Catholicism. This gave rise to an 'us and them' feeling that strengthened the identity of the Catholics. The confiscation of churches and church property was - until the 18th century - also an important element of this. The Catholics were less in agreement about the way in which faith should be professed: especially from the late seventeenth century, the gap grew between Catholics who wanted to continue their faith in seclusion and others who wanted to show themselves exuberantly in the public domain.

Dynamics

Taking the schism between the Roman Catholic and the Old Catholic church in 1723 as her basis, Lenarduzzi also examined the dynamics within the Catholic community. Both camps saw each other as apostates and fought each other with the same instruments with which they had previously fought the Reformists. Lenarduzzi also compared the developments in the Northern Netherlands with those in the Generality Lands, a strip that (on current maps) runs eastward from Zeeuws-Vlaanderen to Germany, and some separate areas in (present-day) Limburg. The Generality Lands only came under the authority of the Republic at a later stage. Lenarduzzi analyses what this means for the nature of the Catholic subculture in those southern regions.

Not spineless victims

By studying two centuries of the Catholic mindset of individual believers, Lenarduzzi exposes the stratification and complexity of the Catholic subculture in the Republic. Contrary to what historians previously assumed, Catholics found inventive and creative ways to practise their faith and succeeded in keeping it alive. They also made it known to the outside world that they had not disappeared from the scene. Lenarduzzi concludes from her research that, during the time that they were oppressed, Catholics were certainly not spineless victims, but rather took their fate into their own hands.

Banner photo: Fishing for souls by Adriaen Pietersz. van de Venne (1614). Allegory on the zeal of the different religions during the Twelve Years' Truce between the Dutch Republic and Spain.

PhD defence Carolina Lenarduzzi

Catholics in the Republic; subculture and counter-culture in the Netherlands, 1570-1750

Thursday 25 October

Text: Corine Hendriks

Mail the editors