National Museum of Antiquities: 200-year partnership with Leiden University

From Caspar Reuvens to the royal grave in Oss, and from ancient images in the Hortus to a table from Naturalis. The National Museum of Antiquities is 200 years old, and throughout this whole period there have been close contacts between museum and university. Curator Annemarieke Willemsen explains this partnership using objects from the anniversary exhibition.

‘Obviously, it all started with Caspar Reuvens,’ curator Annemarieke Willemsen explains. We are in the first hall of the anniversary exhibition in the National Museum of Antiquities (RMO), standing facing a large portrait of Leiden Professor Reuvens. He was the first professor of archaeology in the Netherlands, and even the first in the world. When he was appointed, he was also the first director of the Archaeological Cabinet at Leiden University. 'At that time, it wasn't so much a museum as a collection of archaeological objects for study purposes.'

Archaeological Cabinet

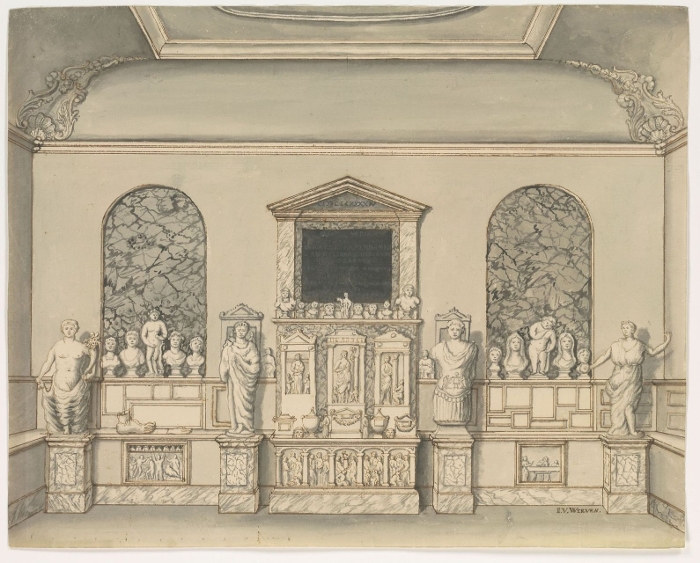

In the next room, one whole wall is taken up with a print of the Orangery in the Hortus Botanicus filled with Greek and Roman statues. In front of it stand a number of the marble statues depicted in the painting. 'Today's visitors can take a walk through the early days of the museum,' explains Willemsen. This is the origin of the Archaeological Cabinet. In 1744 Gerard van Papenbroek, an alumnus of Leiden University, left his collection of Greek and Roman marble sculptures to the university. These sculptures were then placed in the Orangery of the Hortus Botanicus. There are prints of the Orangery showing the statues, and in the exhibition we have placed these Van Papenbroek exhibits back in about the same arrangement.’

As the first director of the RMO, Reuvens set about expanding the collection. The brand-new Dutch royal house provided considerable funding for the acquisition of new exhibits; it was, after all, a national collection. 'William I saw how other countries flaunted their national museums, and wanted the same for the Netherlands,’ the curator explains. Besides archaeological objects that we now associate with the RMO, Reuvens also collected many ethnological objects. 'For him archaeology was much broader than just the ancient world as we define it today. He also collected items from Asia and South America.' These items were later moved to the Museum of Ethnology.

Collection objects moved between Leiden locations

In the past, exhibits were often exchanged between the collections in Leiden. ‘Naturalis, the RMO, the Museum of Ethnology, Boerhaave: these were actually all national collections, with objects intended for study. This is why the items were moved from collection to collection, which meant they could be looked at in a different context.'A good example is the marble table that belonged to - yes, here he is again - Caspar Reuvens. Jean-Emile Humbert, one of Reuvens' ‘agents’ commissioned the table to be made in Livorno: the table top is inlaid with 150 different types of marble. In the centre is the monogram of William I. 'This table was moved to Naturalis, where it was examined as a geological study object. All the different pieces of marble were stored in boxes, separately from the table. When we decided we wanted to have the table back for display here, all the pieces had to be put back together again,' Willemsen says, laughing.

The museum opened its doors to the public in 1838, at Breestraat 18. ‘Since then, exhibiting the objects to the public has also been one of RMO's obectives. Even so, it remains a study collection,' Willemsen says. Many of the objects in the museum are also used for teaching purposes, including a number of plaster casts of famous Greek and Roman statues. 'In the 18th and 19th centuries students couldn't just head off to Rome to view a statue, so these casts were studied instead. They were used by students of archaeology and history, but also, for example, for drawing lessons.’ And now these casts are themselves museum pieces, and they are still used for research, the curator explains. 'A lot more detail can be seen on the 17th-century Trajan's column in our museum than on the original. The original is still standing in the open air and has lost some of its detail because of weathering.'

Joint archaeological research

The museum and university continue to work together on archaeological projects. One example is the prehistory excavation conducted by Professor Leendert Louwe Kooijmans in the 1970s. Students helped with the fieldwork and analysis. 'His many finds and scientific work are the origin of the fact that the study of prehistory here in Leiden is so well known.' And even recently: for her PhD research Sasja van der Vaart-Verschoof studied objects held by the RMO that were found in 1933 in the royal grave in Os. Earlier this year some surprising new data came to light.

We end the tour of the exhibition at the RMO's newest acquisitions: a statue of a young boy dating back to around 600 BC and a late Hellenistic gravestone. 'This gravestone is very unusual; it has a very long inscription. Studying such inscriptions, and through them ancient languages, is a key theme running through the history of our museum. These studies are always carried out together with researchers and students at the university, so they will almost certainly have worked on this particular gravestone.' The circle is complete: the partnership between RMO and Leiden University from 1818 to 2018.

Anniversary activities 200 years of the National Museum of Antiquities

The ‘Two centuries young’ exhibition can be viewed from 25 April to 2 September in the National Museum of Antiquities (Rapenburg 28, Leiden). There are further anniversary activities in the museum throughout the year, including an evening tour, a visit to the museum's restorers or a private collection of one of the curators. For relevant dates, see www.rmo.nl.