How Chilean exiles revalued democracy

During Pinochet’s dictatorship (1973-1990) numerous left-wing Chileans fled to Europe. In exile some of their political views became more moderate. Mariana Perry defended her PhD about this topic in September.

The Chilean coup on 11 September 1973 was quick but effective. In just a few hours General Augusto Pinochet made short shrift of the ruling socialist government. What followed was years of oppression and terror. All those with leftist sympathies went in fear of their lives. According to estimates, some 200,000 socialists, communists and anarchists decided not to leave their fate to chance, but to flee their country. Many of them came to Europe.

Joop den Uyl

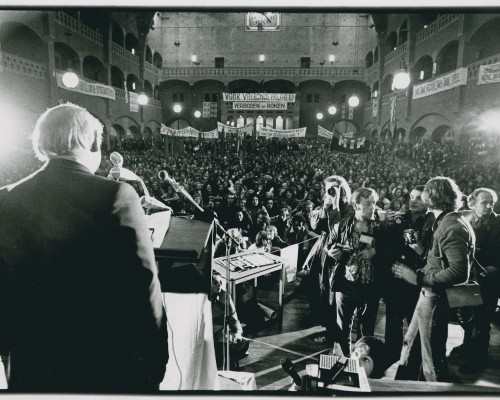

‘These exiles were received here almost like heroes,’ says historian Mariana Perry. ‘Not only in the communist Eastern Europe, but also by the socialist governments in the West. The government led by Prime Minister Joop den Uyl, for example, provided some of the funding for a meeting centre for Chilean exiles in Rotterdam. From there the Chilean exiles were able to organise a democratic opposition movement against Pinochet, and develop their ideas about what would be the best government structure after his downfall.’

Eastern Europe

Their exile in Europe gave the Chilean dissidents the opportunity to experience different forms of government. Initially, many of them went to Moscow, East Berlin and other places in the communist East Bloc, places that most closely reflected their often very left-wing ideas. However, for some of them, their ideas changed over time, Perry discovered. Marxism-Leninism proved in practice to be more callous than the Chileans had expected.

Spies

Jorge Arrate, who worked in the nationalisation of the copper mine during the Allende´s government, was invited to go and live in East Berlin. He was safe there from Pinochet’s spies, but was ordered by the East-German secret service to keep an eye on his close friends. He felt uncomfortable with that and, as a result, he decided to move to the Netherlands.

National unity

The form of government in Western European countries suited the Chileans much better. It also had an effect on their future plans: they gradually came to the conclusion that Chile after Pinochet should resume its democratic path having learned how to work in coalitions, including minorities and aiming at consensus. Free elections and the separation of powers were a goal in themselves. In other words: the exiles were prepared to put all their previous ideas up for discussion. And that is what happened. When democracy resumed in Chile in 1990, the returning exiles formed a government of national unity. At least four members of the first democratically elected government even spoke Dutch.