Research project

Scanning for Syria

Can virtual reconstructions help archaeologists to safeguard scientific information of archaeological objects lost in the armed conflict? And, what is the validity of the method of casting the archaeological objects in the field, followed by CT scan of the casts and virtual reconstruction in the lab?

Dutch archaeologists are making three-dimensional virtual reconstructions of archaeological objects lost in the Syrian civil war.

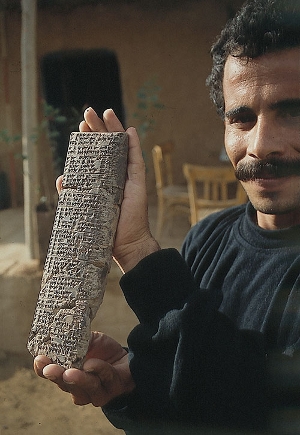

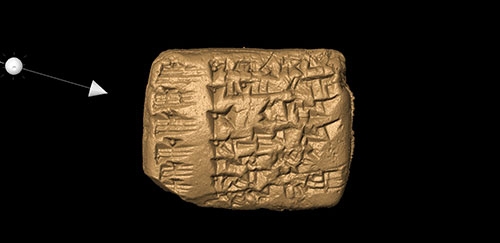

Photo: Tell Sabi Abyad, Syria. Large cuneiform tablet (ca. 1200 BC) shown prior to casting in a plastic mould. The object itself was recently stolen from the archaeological museum of Raqqa (photo Tell Sabi Abyad Project, Leiden) .

Social and scientific relevance

The relentless civil war in Syria is having disastrous effects on the people of Syria and their rich historical and archaeological heritage. Initiatives are being taken across the world to preserve the archaeological materials or at least the scientific information they contain. Archaeologists from the Faculty of Archaeology of Leiden University are experimenting with a new method for safeguarding information from lost artefacts by making three-dimensional scans of plastic moulds. The casts were made in Syria before the war to facilitate specialist analyses and reproductions for public expositions.

Reuters made a videoreport on this 3D solution to Syrian cultural destruction.

In the field archaeologists made casts of three types of objects: clay cuneiform tablets (ca. 1200 BC) from the site of Tell Sabi Abyad (northern Syria) excavated by the Faculty of Archaeology Leiden; phallus-shaped beads from Tell Sabi Abyad (ca. 1200 BC); and prehistoric sherds carrying impressions of textile and basketry from the site of Shir (ca. 6400 BC), excavated by the German Archaeological Institute in Berlin. The original artefacts were stolen or destroyed in 2013.

Kept in the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, the casts have become a priceless source of information, because scientists will want to continue their studies of these objects in the future. Our project aims to reproduce the objects as accurately as possible. We are experimenting with novel ways of making the replicas by using 3-D scanning techniques. This should allow academic study of the information contained in the casts and make this information more widely accessible to scholars and a broader audience.

Why Leiden University?

Leiden was responsible for the excavations at Tell Sabi Abyad before the war and keeps the project archive. Leiden researcher Olivier Nieuwenhuyse is member of the Shir excavation project. In addition, Leiden participates with Delft and Erasmus in the Global Centre of Heritage and Development.

Material & Methods

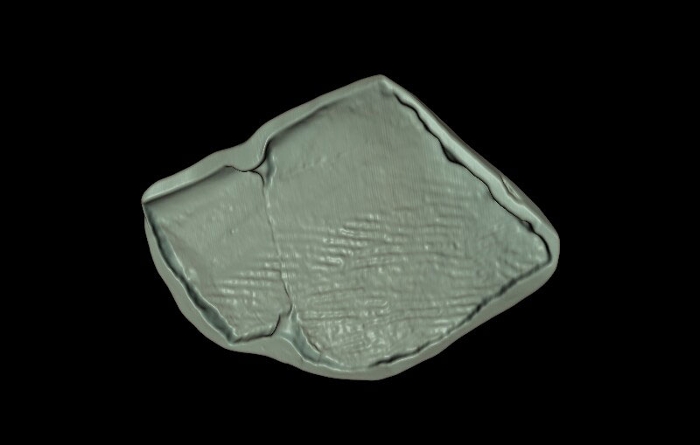

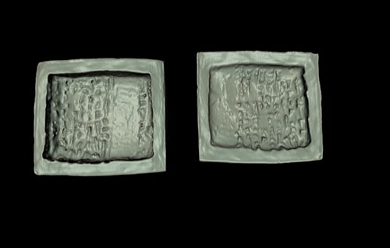

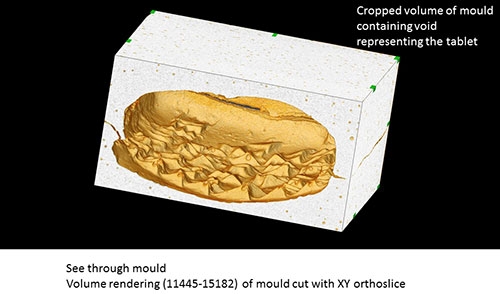

In the field, the casts were made from an industrial two-component plastic material that some of you may know from their dentist (if you’re unlucky …). It quickly hardens while maintaining its flexibility. The traditional way of making the replicas is by filling the cast, for example with gypsum, and removing the cast after the material has hardened. However, this method has its disadvantages. The filling materials often contain air bubbles, reducing the resolution of the reproduction. The soft casts also can break during the removal. As a result, academic institutes end up with clumsy replicas that typically remain poorly accessible to other scholars and totally unknown to the general public.

Searching for an alternative, we decided to apply 3-dimensional scanning techniques. Available technologies have advanced enormously recently. In principle, a virtual reproduction avoids any of the problems above, and the resulting scan can be shared much more easily via the web. If necessary, a hard-copy reproduction can be printed.

Results & Conclusions

With Prof. Christophe Moulherat of the Musée du Quai Branly (Paris) we initiated a pilot study. Two moulds were 3D digitalized by a CT scan operated by the Hospital Clinique Turin in Paris. The results were analysed by Dr. Chloé Vaniet of Vizua. This showed that traditional scanning techniques do not offer sufficient resolution.

We then initiated a second pilot with a micro-CT scanner at the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences of the Technical University of Delft. Working at a much higher resolution this provided images with significantly more detail. Currently we are discussing these results with Assyriologists (the cuneiform tablets) and textile specialists (the cord-impressed sherds) to evaluate the quality of the images and their usefulness for scientific study. Pending the outcomes of these evaluations we shall scan the remaining casts and prepare high-quality virtual reconstructions.

Follow-up

Pending the outcomes of our pilot a follow-up project could be a comparative evaluation of different methods for making digitised three-dimensional reconstructions of archaeological objects: directly from the object or through the intermediary of plastic casts. Further, we aim to organize a public exposition on the project with the National Museum of Antiquities Leiden, the Musée du Quai Branly and the German Archaeological Institute in Berlin. Ultimately the digitised images will be stored in a public archive available to archaeologists, Assyriologists, and interested non-academics from across the world.