‘Drawing for Dummies’, but in the Renaissance

The way the great masters of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries learned to draw is more similar to a present-day drawing class or book than you might think. Professor of ‘Art on Paper and Parchment’ Yvonne Bleyerveld tells us about the art of copying and model books.

The use of model books (books of drawing examples) already existed in the Middle Ages, but only really took off from the sixteenth century, when printed model books became available. ‘You had to learn to draw well, because drawing is the basis of art. And in those days you always started by learning to draw details,’ says Bleyerveld.

Drawing for Dummies

This can be seen clearly in An Academy of Painters by Pierfrancesco Alberti (1584-1638). At the bottom left, a young boy is discussing his work with his teacher. The boy is working on drawing eyes. But why focus on such a small part of the human body? ‘It’s a basic principle of art theory that you start with details and then build that up until you can produce a convincing composition. You learn this by drawing from examples in model books or on loose prints,’ explains Bleyerveld.

In fact, a model book can be compared to a modern-day Drawing for Dummies. ‘In drawing books today, you still see examples that you can copy. These are methods that were also used back then.’

Copying motifs

Model books were therefore actually teaching material, but artists never finished learning. ‘As an artist, you always had to keep training your eyes and hands. That’s why artists were encouraged to study nature and light in the open air. You could use the drawings you produced there later, as models for your paintings,’ she says. This is how the first personal sketchbooks came into being. The small books fitted perfectly into a pocket or travel bag and you could take them everywhere with you. If an artist saw something interesting, he or she could make a sketch of it. ‘They were actually personal model books that you could consult later if you were looking for a specific motif for an artwork.’

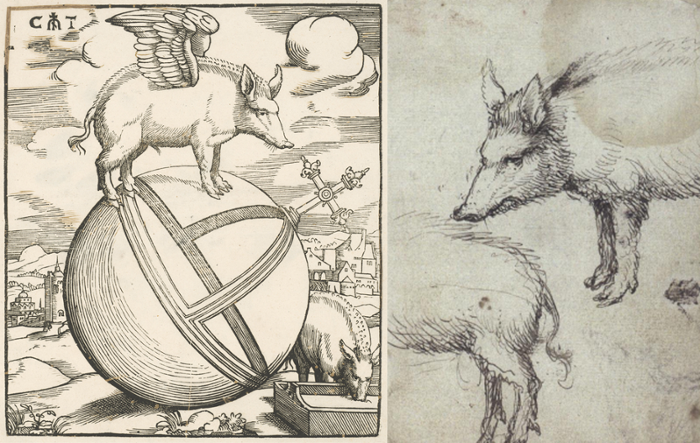

A few years ago, an anonymous sketchbook was attributed to the Amsterdam printmaker Cornelis Anthonisz (c. 1505-1553). ‘My colleague Daantje Meuwissen discovered that there’s a direct relationship between his prints and several motifs from the sketchbook,’ confirms Bleyerveld. ‘You only have to look at the images to see the connections. A pig in one of Anthonisz’ woodcuts, for example, is almost entirely copied from the sketchbook.’ This is the oldest personal sketchbook of a Dutch artist known to have survived.

However, it also happened that artists – both professionals and amateurs – would copy motifs from standard model books. The Oorspronkelyk en vermaard konstryk tekenboek (‘Original and renowned artful drawing book’; c. 1650) by the Utrecht artist Abraham Bloemaert was popular because of the many useful drawing examples that it contained. ‘Books with drawings of eyes, hands and feet are very practical,’ says Bleyerveld. ‘Model books weren’t limited to drawings of the human body; there were also books with landscapes and animals. If an artist liked a particular aspect of a print or wasn’t so good at drawing certain motifs himself, he copied them into his own work.’

Changing function

But why is it that if you say you’ve copied something today – no matter how good it looks – the best you can expect is a strained compliment? Bleyerveld says that this relates to the changing function of art. ‘Until the eighteenth century, art had a clear educational function: artworks usually had to convey a moral, didactic or religious message. Representations, for example from the Bible or mythology, had to be clearly recognisable and were depicted according to certain conventions. You learned to do that well by copying,’ she says. But from the nineteenth century, this dogma began to change. ‘Then we see the emerging idea of the romantic artist who, as a creative spirit, invents all kinds of things. It then becomes more about the beauty and creativity that art should produce: l’art pour l’art - art for art’s sake. At that point, copying acquired a bad name.’

This is why today we associate copying with a lack of creativity and talent. But it certainly doesn’t mean that artists in the past weren’t creative. ‘There was the idea of emulation: you imitate your predecessors, but you must also try to surpass them by doing things slightly differently. That’s where the creativity was.’

Banner: Abraham Bloemaert, Studies of hands, arms and several heads of a younger and an older woman, 1574 - 1651. Red chalk. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum.