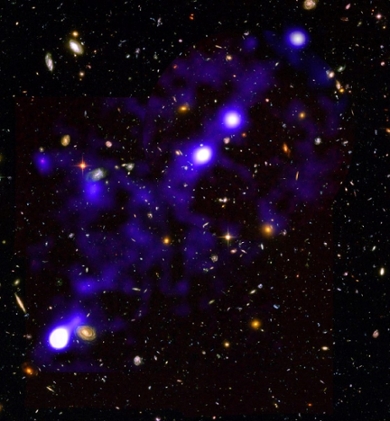

Astronomers map the cosmic spider web

An international team of astronomers from Leiden Observatory and others, has for the first time mapped a piece of the dark, cosmic web. The research strengthens the hypothesis that the young universe consisted of huge numbers of small groups of newly formed stars. The astronomers publish their findings in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Nodes of the web

Astronomers have long assumed that the billions of galaxies in our universe are connected by a huge cosmic web of gas flows. The web itself is hard to see because it radiates almost no light. The nodes in this cosmic web had already been mapped using quasars. These are supermassive black holes in the centers of galaxies whose surroundings emit enormous amounts of light. The light is then scattered by the cosmic web and so the web around the quasars becomes visible. Unfortunately, quasars are rare. Moreover, they are only located at nodes of the cosmic web. As a result, they provide a limited view.

Now, for the first time, researchers have managed to see a small section of the cosmic web without using quasars. A team led by Roland Bacon (CNRS, Centre de Recherche Astrophysique de Lyon, France) focused the Very Large Telescope for 140 hours (spread over six nights between August 2018 and January 2019) on part of the iconic Hubble Ultra Deep Field.

Scattered light

Using the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE), the researchers were able to capture light from groups of stars and galaxies that was scattered by gas filaments of the cosmic web. This light originates from about two billion years after the Big Bang.

The observations showed that possibly more than half of the scattered light comes not from large bright radiation sources, but from a sea of hitherto undiscovered galaxies with very low luminosity that are far too dim to be observed individually.

Tiny galaxies

The research strengthens the hypothesis that the young universe consisted of vast numbers of tiny groups of newly formed stars. Co-author Joop Schaye of Leiden Observatory: 'We think that the light we see comes mainly from young galaxies that each contain millions of times fewer stars than our own Milky Way galaxy. Such tiny galaxies were probably responsible for the end of the cosmic dark ages, when less than a billion years after the Big Bang the universe was lit up and heated by the first generations of stars.'

Co-author Michael Maseda, also from Leiden Observatory adds, 'The MUSE observations thus not only give us a picture of the cosmic web, but also provide new evidence for the existence of the extremely small galaxies that play such a crucial role in models of the early universe.'

In the future, the astronomers would like to map larger pieces of the cosmic web. That's why they're working to improve the MUSE instrument so that it provides a two to four times larger field of view.

Scientific paper

Original press release on www.astronomie.nl