How do you tell the story of eighteenth century princesses?

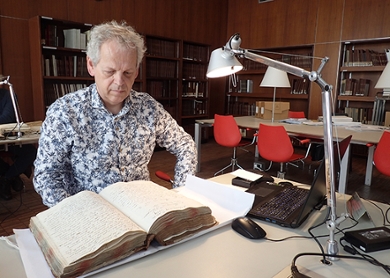

Historian Joost Welten has written a book entitled 'De vergeten prinsessen van Thorn' (The forgotten princesses of Thorn). For his book, he analysed thousands of handwritten letters from the eighteenth century, mainly written in German and French. His personal mission is to visualize the daily lives of these noblewoman and to give them an academic nuance as well as making them transparent to a broad audience. Welten: 'The latter is proving the greatest challenge for me.'

An intriguing, yet unknown history

'It all started when I was thirteen,' Welten says. 'During a school trip we were planning to visit Thorn, a village full of monuments, located about fifteen kilometres by bike from our school. When we arrived, it turned out the museum was closed. The church was closed too, in fact, the village was deserted. We spent twenty minutes walking around, after which our teacher decided to go back. But the atmosphere of the place remained with me. It was clear that it had an intriguing, yet still unknown history.

Tens of years later, in 2015 – in the meantime, I had become a historian and an academic – I revisited Thorn. I found out that there very little research had been done on the town, so I decided to do a bit of research of my own. I started in the archives of the stift ( ed. : ‘endowment of estates, and the territory ruled by an imperial abbess’) Thorn, located in Maastricht. There I found the blueprints of the abbess’s palace as well as thick stacks of letters related to the building process. With this information it was possible to make a reconstruction of how the palace would have looked, both inside and outside.

Thanks to the correspondence, it became clear to me that Kunigunde of Saxony, the last Princess-Abbess of Thorn, was closely involved with her palace in Thorn and had been there many times. According to popular belief, she did not have a court of her own, she would not have invested in her palace and would have rarely been to Thorn. Nor would she have played an individual role, but always remained close to her brother, the Archbishop-Elector of Trier. This turned out to be a myth conjured in the ninetheeth century, when woman were not allowed to have a place of their own in history.

When I realized there had been a proper court life in Thorn, I started looking for written traces of Kunigunde of Saxony as well as other noblewomen who resided there in the eighteenth century. It is of these women in particular that a good amount of correspondence has been preserved.'

One of the biggest private archives in the world

'Apart from that, I was very lucky. In the last couple of years, a lot of archived materials have been made public; some of it is even on the internet. For example, the private archive of Xavier of Saxony, the brother of Kunigunde, which contains nearly a hundred thousand letters, has been uploaded online. Through the letters from Kunigunde and her other brothers and sisters to Xavier, we can follow their private lives from week to week.

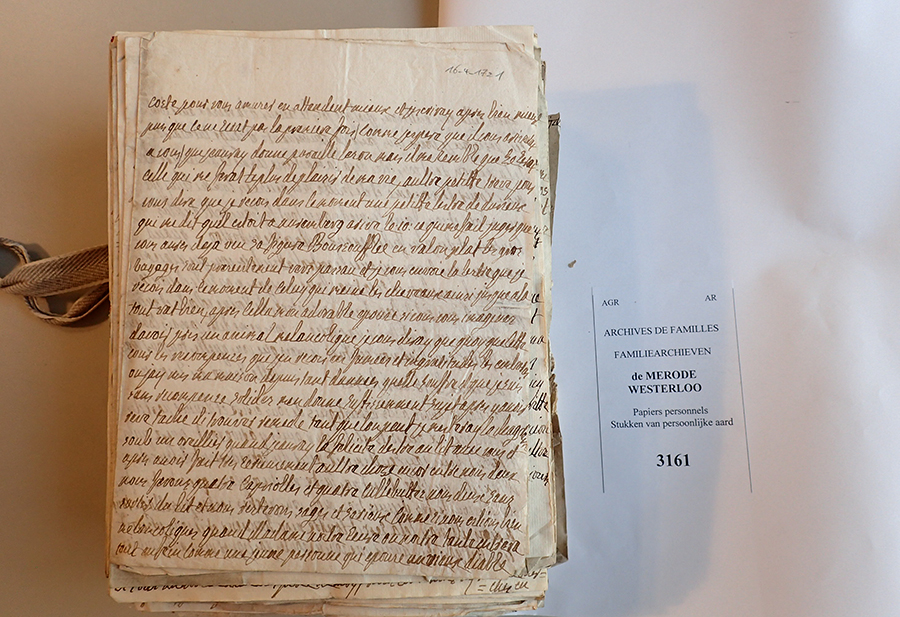

An inventory was released in 2014 of the Merode archive, the second biggest family archive in Belgium. The archive has been preserved in the National Archives of Belgium in Brussels, and has now been made available to the public. The 14,000 inventory items contain a lot of correspondence from and about the women of this noble family who lived in Thorn during the eighteenth century. Women would write about everything: their travels through Europe, dance parties or their search for money to pay off their debts.

I was also very fortunate with the archive of the Salm Salm family. This archive remains in a private collection at Anholt Castle in Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany. That huge family archive has hardly ever been consulted for scientific purposes before. In the summer of 2017 I went there for the first time, more or less without any prior preparation, since I had no idea what I would find there. I only knew that princesses of Salm Salm lived in Thorn during the 18th century. I was only able to view inventories when I got there, which had been written by hand a long time ago, in the barely legible Kurrent style of writing. But when I started requesting materials, I found one treasure after the other: all of them large bundles of private letters from eighteenth century women, which had never been analyzed before.'

Processing information with digital humanities

'The big advantage of the digital era is that it is possible to photograph or scan files integrally. This has made it possible to process far more documents than we could in the past, and it has also allowed us to analyses the information in more detail. The previous generation of researchers was confined to reading the documents on the spot, in the archive, and had to decide immediately whether things were relevant to their research or not. If it was, they made notes of it, but all the other information was lost. When mapping networks and visualising daily life, it is the little details that may appear to be irrelevant that are of major importance. In the past couple of years, every day I have spent a few hours in my own digital archive. With every detail I encountered, I wrote down who it concerned and when it happened. By doing this, I was able to reconstruct storylines surrounding people. I found out, for example, that women – often widows – maintained continuity in noble families through expansive networks, which they maintained through writing letters. But also that the same women would learn their songbirds melodies by using music boxes. The smallest details become meaningful. I got to work on this systematically, using a lot of base materials. Knowledge of multiple languages is essential in doing this kind of research. Many pieces have been written in German or French, some in Italian, Latin of Dutch. You need to know these languages to do research like this.'

'In my book, women are the main focus'

'We don’t know a lot about the lives of women in the eighteenth century, because there are very few sources that depict their lives. Women were not allowed to hold military positions, nor a position in the state apparatus. Only under special circumstances could she be an entrepreneur. Since women barely had a place in public life, little has been recorded about them. Yet using this correspondence, we are able to trace a lot of information. In this book I have revealed the female counterpart to the male world of generals and statesmen. In my research these women appear as self-conscious people who are well-read, musical and interested in a broad range of subjects. This is why I have tried to make my book something that puts these women in the spotlight.

The research also has an impact on museums, as we now know that a lot of paintings depict different people from those we originally thought. Information from catalogues did not match information from visual research I did together with my friend Lena Reyners. Thanks to our investigation, data about the origin of these paintings can now be amended.

I also get requests from museums to advise them on exhibitions about nobility from that period. I try to help them think about ways to visualize history, without using too much text.'

Mission accomplished?

'I would love to publish this book in Germany, after all, the book is mainly about the lives of German noble families. It has been written in a more approachable style than German scientific articles. This method of making your work more easily readable is almost unknown to German academics, which is why I established the ‘Forgotten princesses of Thorn’ fund to help finance the German publication. I believe German people also like to read about this period, which hasn’t been ‘contaminated’ in the same way that the 20th century has been.

In 1763 Kunigunde of Saxony, one of the main characters in my book, performed one of the main roles at the opening night of the opera Talestri: Queen of the Amazones, which was written by her sister-in-law Maria Antonia of Bavaria. A few of the arias from this opera were sung at the book presentation of The forgotten princesses of Thorn, something which had never happened before in the Netherlands. The performance was praised so highly by both the performers – under the direction of Korneel Bernolet – and the audience that there are plans to perform the entire opera and record it on CD. Of course it would be amazing if this research project were to lead to an actual opera; it is something I would never have even considered.'

Text: Nathalie Borst

Send an e-mail to the editors

-

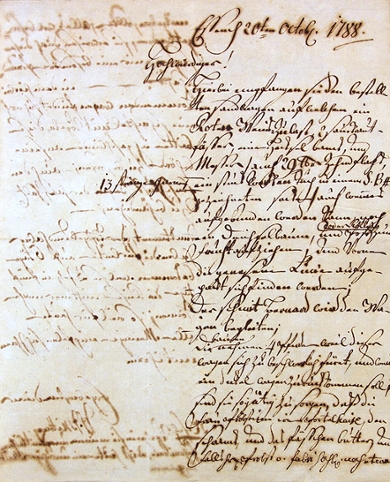

1: ‘One really nice item is the lock of hair which a German noblewoman sent along with her letter. These sorts of things make a historian happy, especially when it leads to uncovering something which has remained hidden until now’ Welten says. -

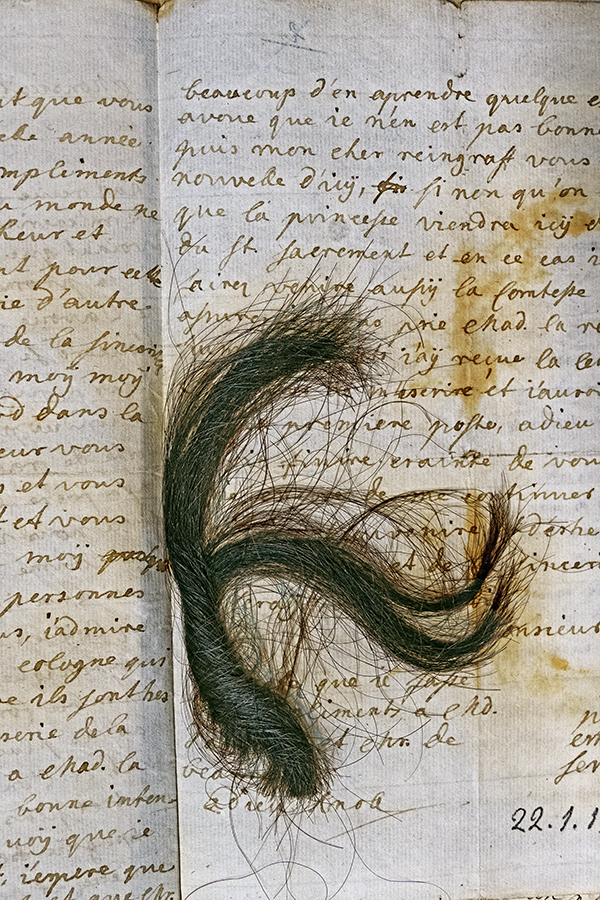

2: The so-called Kurrent style of writing is the handwritten form of pre-modern German. There is a high degree of variance within Kurrent. It shows in the three styles of handwriting depicted on the photographs. -

3: The so-called Kurrent style of writing is the handwritten form of pre-modern German. There is a high degree of variance within Kurrent. It shows in the three styles of handwriting depicted on the photographs. -

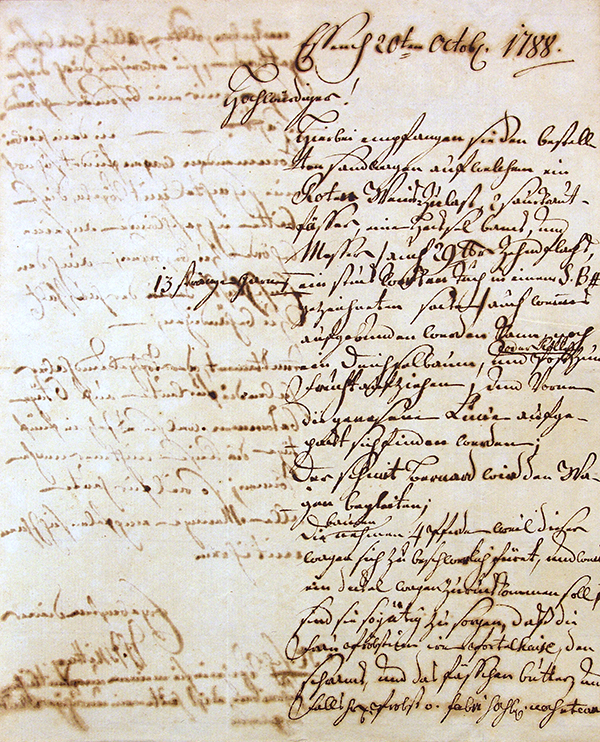

4: A bundle of letters in the French language