Better insight into competition between microbes

It is mostly rainfall and soil acidity that determine which microbes survive in a particular habitat and which do not. This knowledge is important for maintaining biodiversity. Leiden environmentalists contributed to the research. Publication in Nature on 1 August.

Researchers from the Leiden Institute of Environmental Sciences (CML), Nadia Soudzilovskaia and Peter van Bodegom, participated in a research consortium that established the global distribution pattern of micro-organisms in soils and oceans. For the first time, they investigated how micro-organisms are spread over the different habitat types and climate zones of the earth. Nineteen universities from seven countries collaborated on the research.

Deadly competition

Researchers in the consortium took samples of soil and ocean water from two hundred different ecosystems. Using new metagenomics methods - where genetic material is analysed directly from soil samples - they examined the composition of the microbial communities and looked at how the micro-organisms compete with each other. They discovered that environmental conditions, especially precipitation and the acidity of the soil (pH-level), regulate the distribution of microbes on Earth. In addition, they saw that bacteria and fungi prefer different habitat types. Competition between micro-organisms takes place by producing antibiotic compounds that kill competing microbes. It is striking that the same processes occur in both soil and water.

Maintaining biodiversity

The research makes clear how microbes create part of the global biodiversity patterns. Microbes or micro-organisms, such as bacteria and fungi, regulate plant and animal feeding processes, the nutrient cycle and the carbon storage in ecosystems. Until now, however, researchers did not know which microbes are involved in different places on Earth. Nor did they know how these microbes compete with each other for space and nutrients and why in a given environment particular microbes win the competition. Without knowledge of the distribution patterns of micro-organisms, a complete understanding of the nutrient and carbon cycles of the ecosystems of the Earth is not possible. And without that insight, good management measures to preserve biodiversity cannot be developed.

Seven collaborating countries

The nineteen universities that were part of the consortium are based in Estonia, Norway, Sweden, Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Spain. In the Netherlands, Wageningen University was involved, in addition to Leiden University.

The article Structure and function of the global topsoil microbiome appeared in Nature on 1 Augustus.

Text: Corine Hendriks

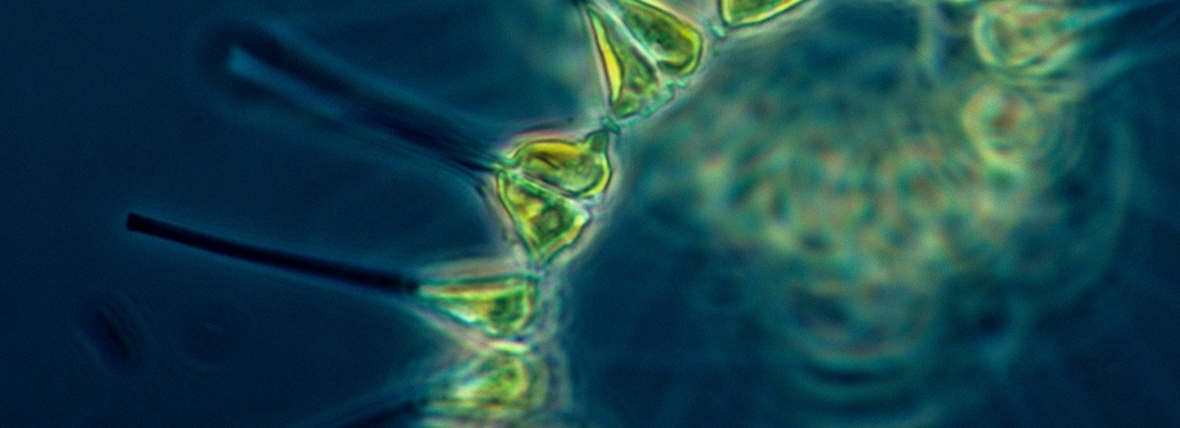

Banner photo: Plankton forms the base of the food chain in the oceans. It consists of animals and plants smaller than 200 nanometres (= one billionth of a metre). © Marine Science Today