The art of control without repression

How did the Arabs manage to maintain an empire based on Islamic principles for three hundred years? Arab expert Petra Sijpesteijn and her team will be examining this question over the coming five years, focusing on the correspondence of ordinary people. The research is being funded by an ERC Consolidator Grant.

Difficult to control

After the death of Mohammed in 632, his successors managed to expand the Arab Empire to cover an area stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to India. It was a huge area to control, particularly because of its enormous ethnic, linguistic and religious diversity. Nonetheless, the empire remained intact for three hundred years. How did the Arabic rulers manage to achieve such a feat?

Value system

Sijpesteijn wants to find out what held the Islamic Empire together. We already know a lot about the Arab Empire in the period from 600 to 1000 AD, but that knowledge is mainly about the upper strata of society. What Sijpesteijn wants to know is what daily life was like under the rule of the Arabic conquerors, and how the Muslims managed to keep all the different ethnic, linguistic and religious groups together by making them part of the empire. There were revolts, but not serious enough to affect the cohesion of the empire.

Raising taxes

We know that the Arabs raised taxes among Christians, Jews and converts (who were not regarded as fully Muslim). For these groups, paying taxes was a way of buying their religious freedom. Muslims also had to pay taxes, in their case alms tax. The giving of charitable donations to the poor and less well off is one of the five core tenets of Islam. Who should collect the taxes and who should be responsible for distributing the alms - the government or the taxpayers themselves - was a hotly debated issue. There was some conflict between local and central interests, but the discussion ultimately resulted in a shared interest that even contributed to the solidarity of the empire.

New material

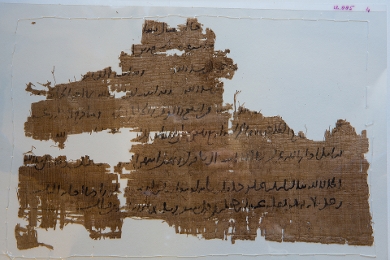

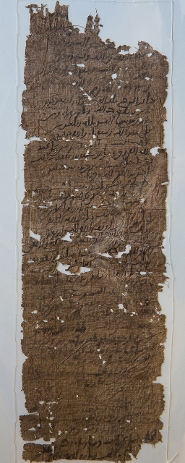

The time is ripe for this research, Sijpesteijn believes. 'In recent years a lot of letters and fragments have turned up from the time of the Islamic Empire, particularly in Egypt, Afghanistan and Iran, often on rubbish tips in dry parts of these countries: arid conditions are ideal for keeping the material intact. With irrigation techniques extending the usable land area, these rubbish tips are now being exposed. The letters often contain requests from ordinary people to more senior members of society. The arguments used by the writers reflect a particular value system that is related to social expectations. Just like today, arguments were put forward that were expected to have a particular effect.'

Garrison cities

We already know that garrisons that had conquered an area stayed there in army camps to make sure that the region remained under Arab control. The soldiers were paid from the taxes. As everyone needed at least food and clothing, the local economy flourished, particularly once traders from outside the garrison cities found their way to the army camps. 'The assumption is that the Arabs just acted randomly,' says Sijpesteijn, 'but I don't believe that. I think that, as well as being good politicians and warlords, they were also good organisers. They had to keep all those different groups of people together, without resorting to repression.'

Examples

Sijpesteijn mentions a couple of examples. 'A mother whose son has been imprisoned writes to an official. Besides God, there is no one to whom I can turn, apart from yourself... The writer of the letter raises the official almost to the position of a god in order to cajole him into helping her. Another letter is from a prisoner asking the governor to take another look at his case. I work day and night to maintain my wife, my children and my slaves, and still I am unsuccessful. This person expects his hard work to have an effect on the governor's attitude towards him.'

Contemporary letters

Some of the letters are surprisingly contemporary. It was usually women who wrote the letters, or who had someone else write the letters for them. Widows with children, or families with children asking for attention to be paid to their precarious situation. We have no clothes to wear and there isn't even a single morsel of food to eat. 'My first thought was that it all sounded exaggerated,' Sijpesteijn commented, 'but, of course, it's meant rhetorically. There's also an interesting letter from a caliph to a steward who has apparently run off. The caliph wants him to return. I've helped you so many times. 'The caliph could have resorted to threats: if you don't come back I'll have your head chopped off, a punishment that was by no means uncommon at the time. The way that people tried to persuade one another to do something says a lot about what their expectations were of one another, how society was structured and how citizens were expected to conduct themselves. This pattern of mutual expectations and the behaviour it led to is what held society together.'

Work enough for five years

Sijpesteijn started her research in January, with the help of three PhD candidates and two postdocs. They can start their work in the University Library where there is a small collection of letters. Larger collections can be found in Berlin and Vienn, although in some countries, such as Afghanistan and Iran, access to the material is difficult. Sijpesteijn wants to go to Egypt herself to be present at an excavation. At the moment her desk is full of material from all kinds of sources. There's enough information here to fill five years of research.