Research project

Formation of Islam: Topics

The FOI project has a number of topics it aims to investigate. These are: State, Economy, Culture and Papyri. You will find links to bibliographies on this page.

- Duration

- 2009 - 2015

- Contact

- Petra Sijpesteijn

State

The FOI project aims to examine the extent, character, competency, and ambition of the Egyptian State from the time of the Islamic conquest as well as the steps – military, administrative, and religious – by which it extended its reach, and what this tells us about the origins and evolution of Muslim ideas of rulership, religion and power.

Other questions such as how "the State" was conceived and how Egypt’s social and administrative infrastructure – the machinery of government and law – were co-opted and the Islamic State given shape will also be central.

Below one will find links to bibliographies on administration, taxation, and agriculture and landholding as well as lists of fiscal terminology and governors attested in papyri. Within the framework of the FOI project’s first roundtable (3.6.2010) a study into two fiscal terms was made of which the results can also be found below.

All the bibliographies and lists are works in progress. Feel free to send suggestions and/or remarks to foi@hum.leidenuniv.nl.

By G. Schenke. Version 2.12.2010.

What went before

In Roman times charges were assessed upon the person, the land, animals, the occupation and services, sales and transfers, movement of goods and people, and real and personal property.

The most import tax was the poll tax (epikephalaion/laographia), paid by all male inhabitants from the age of 14 to 60, rate varying from nome to nome (at reduced rate in the nome capitals).

Roman citizens in Egypt, as well as the citizens of the Greek towns (Alexandria, Antinoopolis, Naucratis, Ptolemais) were exempted – since 314 AD fifteen-year indiction cycle for tax payments in use (formerly a five-year cycle existed). Tax collection was liturgical work.

Salaries of state officials and the maintainance of the army had to be provided for by the population through taxes.

Under Justinian about 2 million solidi in anual taxes are calculated for Egypt.

The same tax income of 2 million solidi from Egypt is assumed for the time after the Arab conquest of which about 25 % went to the caliph in Medina. Thus, it would seem that there was no tax increase for the population due to the Arab conquest.

Taxes after the Arab conquest seem to have been essentially those of Byzantine times, i.e. distinct from the Arab jizyah (poll-tax) and kharaj (community tax).

Taxes were paid in money as well as in kind, depending on the type of tax.

The main tax demands under Arab rule

- “public taxes” (δημόσια) or “gold-taxes” (χρυσικὰ δημὸσια) paid in money, consisting of

- land-tax (δημόσιον)

- poll-tax (διάγραφον also called ἀνδρισμός) paid only by men for the current year

- expenses-tax (δαπάνη or dapanē nalmoumenin) paid one year in advance, intended for the expenses of the local officials in general, the Muslim army, soldiers and officials, expenses for the governor (dux), and expenses for the caliph - xenion-tax (ξένιον) paid in money, also known as xenion of the Emir (xenionmpamira) or ξένιον τοῦ amir al-mu’minin, seems to have been intended for “strangers” or “guests”, most likely to cover the expenses of travelling officials

- corn-tax (ἐμβολή) generally paid in kind, in wheat or barley

- trade tax or other special taxes could be levied on people whose income did not derive from holding land, such as

- weaving-tax (temosin (δημόσιον) ntale štēn, “garment weaving-tax”). Three documents from Bala’izah, P.Bal. 132–134, attest the payment of this particular tax as a special form of δημόσιον. P.Bal. 132,2 (mid 8th cent., after 740!) has: temosen entale štēn, P.Bal. 133,1f.: temosin ntale štēn, and P. 134,3: temos ïonpsōḥe“weaver/weaving-tax.”

- new tax (dēmosion nbrre) P.Bal. 214,16 - Additionally, a number of special taxes and personal services could be required, such as

- dyke-service

- sailor-service

- government service

- requisitions in kind or money for public needs, allowences to officials and Arab settlers, provisions for workmen and sailors, naval construction, or public buildings

could be among the things requested to be performed or paid by particular people of the community

Tax assessment

Taxes could be paid in full or in instalments (ἐντάγιον/κατὰ ἐντάγιον).

Methods of tax assessment and tax collection were likewise essentially those of the Byzantine period and organized not by the central Arab government, but by local officials.

Duty of the local officials was to keep a register (κατάγραφον) of each χορίον, listing all tax-payers with their amount and type of holding (vine-land, date-palms, acacias) and the amount of taxes they had to pay.

Size and quality of the land holdings determined the tax amount levied.

Likewise, lists of craftsmen (τεχνῖται) were part of such a tax register, with the specification of the type of craft (τέχνη) and the tax amount due.

Gathering and reporting of information on tax payers was carried out and provided from within the community.

These tax registers were then regularly sent up to the central treasury at al-Fustat (Cairo) where they were used as the basis for the yearly tax demand of all ordinary and extraordinary taxes on each pagarchy as a whole and each village or administrative unit within it in particular.

Unless major changes took place within a local community, the yearly tax quota usually remained the same.

The collection of taxes did not happen automatically, rather the governor had to make a requisition for each tax collection

The amount of taxes demanded by the new Muslim rulers seem to have been quite high. One finds people struggling and borrowing money in order to be able to pay their taxes. Also the monastic communities appear to have been heavily levied.

The tax demand was levied on the community as a whole whose authorities then had to break it down into individual tax demands according to what each member of the community was able to pay. Therefore we find this tax varying in amount in the individual tax-receipts. The poll-tax, however, was to be paid only by the non-Μuslim male members of the community after having reached a certain age.

A document from the monastery of Apa Mena relates to the appointment of a superior of a monastery who at this period had to make himself responsible for the payment of its taxes which clearly had to be paid from his own resources to a considerable extent. It seems that the disappearance of many monasteries during the middle of the eighth century was directly due to heavy taxation. P.Bal. 290 shows that the monastery had to pay in one single year more than 88 solidi in taxes alone.

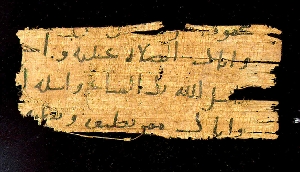

Papyrological evidence

Next to the documents one would expect, such as private and official letters, contracts, complaints, and juridical solutions, the organisation of food supplies and general diakonia, as well as the seemingly overwhelming evidence of the amount of taxation, one can also discover glimpses of a new duality of life for the Egyptian population. Used to frequent changes in oppression, the Egyptian population seems to have coped rather well with the novelties of a different era. The main changes affectively seem to have been administrative and linguistic. Orders were now given in a different foreign language and script.

For the payment of his taxes, the payer would first receive a tax demand (entagion) stating the amount due for his taxes. After handing the money over, he would be given a tax receipt mentioning his full name, the amount he paid for the particular indiction year (tax year circle), as well as the date on which he paid it. A formal signature by one of the known tax-collectors would give this document its authority.

General questions: When were monks taxed with the diagraphon? There seems to be a discrepancy between the litereary and documentary sources concerning a tax exemption for monks on the diagraphon.

Bibliography

For a more extensive bibliography, see [Bibliography of taxation].

H. I. Bell, P.Lond. IV, pp. xxv–xxxii.

S. J. Clackson, P.Mon.Apollo, pp. 23–26.

A. Delattre, P.Brux.Bawit, pp. 101–104.

N. Gonis, "Arabs, Monks, and Taxes: Notes on Documents from Deir el-Bala’izah", ZPE148 (2004) 213–224.

P. E. Kahle, P.Bal. I, pp. 41–45.

H. Heinen, "Taxation in Roman Egypt", The Coptic Encyclopedia, VII, pp. 2202b–2207a.

F. Hussein, Das Steuersystem in Ägypten von der arabischen Eroberung bis zur Machtergreifung der Tûlûniden 19–254/639–868 mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Papyrusurkunden, Heidelberger orientalische Studien 3, Frankfurt am Main, 1982.

K. Morimoto, The Fiscal Administration of Egypt in the Early Islamic Period, Asian Historical Monographs 1, Dohosha 1981.

J. B. Simonsen, Studies in the Genesis and Early Development of the Caliphal Taxation System with special reference to circumstances in the Arab peninsula, Egypt and Palestine, Copenhagen 1988.

K. A. Worp, "Coptic Tax Receipts: An Inventory", Tyche 14 (1999) 309–324.

By M.A.L. Legendre & K. Younes.

For references to fiscal terms used in this text, see below. For a bibliography on the early Islamic taxation system, see below.

Introduction

In the early Umayyad period non-Muslims in Egypt were paying land- and poll-tax levied together under the term ğizya (that could be employed with a technical meaning when specified as ğizya al-arḍ or ğizya al-ra's) and Muslim were paying ṣadaqa. Those were the permanent public taxes but there were also temporary imposts (so-called extraordinary taxes among which were fuḍūl, rizq, …). The poll-tax was paid in money and the land tax could be paid in money or in kind, the later being called ḍariba. In that sense, only the term ğizya appears in the fiscal and administrative documents from the first part of the Umayyad period to designate the permanent public taxes paid in money being poll- or land-tax.[1]

Increasing numbers of conversions and implementation of Muslims and converts in the countryside acquiring and farming lands as well as redefinition of the status of conquered land, led progressively to the separation of poll-tax (under the term ğizya) from land-tax (under the term ḫarāğ).[2] This solution is attributed in the narratives to the caliphs ‘Umar II (r. 99-101/717-20) and Hishām (r.105-25/724-43) and his finance director and governor in Egypt ‘Ubayd Allāh b. al-Ḥabḥab.[3] This separation was theorized in the law schools in what became the later dominant legal opinion of interpretation of ḫarāğ as rent on the conquered land whose income should benefit all Muslims.[4]

However this change of terminology is not visible at this date in the papyri from Egypt. The term ḫarāğ is of Persian origin and might have been used in other parts of the Empire earlier than attested in Egypt.[5] Only in the mid-2nd century A.H., we find the first attestation of ḫarāğ in a papyrus (P.David-WeillLouvre 16 a quittance dated 156AH/773AD) and in this project we have looked at the documents dated to the first 200 years of Islam in Egypt in order to define the exact contexts in which terms ğizya and ḫarāğ were used in this period.

1. Attestations of the term ğizya

a. Type of documents:

There are seventeen collective tax demand notes issued in the name of the governor Qurra b. Ṧarīk to the people of several villages in the district of Aphroditô. All these documents are dated of the year 91/710, the tax involved (tax in money and land tax in kind) were, however, due for the impost of year 88/707. The table below details the amounts and localities to which those demand notes were addressed:

| Nr | Village | Money tax (ğizya) | Land tax in kind (ḍariba) | Edition |

| 1 | Ṧubrā Baqawnisa | 490 | 128+1/2+1/12 | P.Heid.Arab. I a |

| 2 | Šubrā ’Anfidawduna | 131+1/3 | - | P.Heid.Arab. I b |

| 3 | Šubrā Bunāna | 47+1/6 | 5 | P.Heid.Arab. I c |

| 4 | Šubrā Qaramiyyaẗa | 25+1/3 | - | P.Heid.Arab. I d |

| 5 | Unknown | 30+1/6 | 18+1/2+1/4 | P.Heid.Arab. I e |

| 6 | Munyat Ṭawrīna | 98 | 18+1/2+1/4 | P.Heid.Arab. I f |

| 7 | Munyat Kanīsat Māriyya | 5 | 88 | P.Heid.Arab. I g |

| 8 | Munyaẗi Faruwaha | 10 | - | P.Heid.Arab. I h |

| 9 | Munya Barbariyya | 47+1/2 | - | P.Heid.Arab. I VI |

| 10 | Kanīsat Māriyya | 461+1/2 | - | P.Heid.Arab. I i |

| 11 | Badiyadusa | 400+1/2+1/3 | 273+1/3+1/12 | P.Heid.Arab. I v |

| 12 | Badiyadusa | 253+1/6 | 250 | P.Heid.Arab. I k |

| 13 | Badiyadusa | 104+1/3 | 235 | P.Heid.Arab. I l |

| 14 | Šubrā Bisīrū | 30+1/6 | 11+1/3 | P.Cair.Arab. 160 |

| 15 | ʾUrūs Mariyya | 37 | - | P.Cair.Arab. 162 |

| 16 | Šubrā ʾAǧiyuh | 28+1/6 | - | P.Cair.Arab. 161 |

| 17 | Hurūs ʾAbīrmayūṭus | - | P.Cair.Arab. 163 |

There are two tax demand notes to individual tax-payers.

- The first document is issued in the name of the financial director ‘Ubayd allāh b. al-Ḥabḥāb (in office 102-116/720-734) to a certain Ǧirǧa b. Lonǧīn(os) residing in Fusṭāṭ to pay for his poll-tax (ǧizyat ra’sika) of the year 131/713 two dīnārs and one eighth and one sixth and a half carat.[6]

- The second document is issued in the name of a certain Fuḍayl b. Ḥakīm probably a local administrative official to a certain Indūna Hārūn. The text mentions three different kind of taxes: poll-tax (ǧizyat ra’sihi), land-tax (ǧizyat arḍihi) and extraordinary tax intended for the commander of faithful (khāṣṣat amīr al-Mu’minīn). The amount is missing.[7]

There are two tax receipts issued in name of the governor.

- The first is issued in the name of governor Mūsā b. Muṣ‘ab (in office 167-168/785). The receipt states that were received from the tax payer (name lost) ten dinars for the payment of his poll-tax (ǧizyat ra’sika) for the ḫarāğ of year 168/785.[8]

- The second is issued in the name of ‘Abbād b. Muḥammad (in office 196-198/812-813). The receipt states that were received from the tax payer Abqīra the baker the ḫarāğ of the year 196/812. The amount of his poll-tax (ǧizyat ra’sika) is a half a dinar. At the end of the receipt, it is said that the tax payer paid himself 12 carats.[9]

There is one list of individual tax payers[10] where three tax payers paid the first installment of their poll-tax (ǧizyat ru’ūsihim). The amount is given in fractions of dīnārsas follows:

Johannes Armāhe 2/3 1/24 ● 1/24 1/8

Simʿūn Johannes 2/3 1/24 ● 1/24 1/8

Ǧirǧa Mūsīs 2/3 1/24 ● 1/24 1/8.

There are ten work permits. In these work permits, state officials allow tax payers to travel either to Fusṭāṭ, Lower Egypt (asfal al-arḍ), Upper Egypt (al-ṣa‘īd) or Aswan in order to earn money to pay their taxes (fī ǧizyatihi or li-wafā’ ǧizyatahu) and to earn their living (wa-ma‘īšatihi). The period of the permit varies from one to five months.[11]

b. Meaning attested:

Therefore we find term ğizya used with the following meanings in the first 200 years of the Islamic calendar in Egypt:

- Money tax as the general public impost, this meaning is found in collective tax demand notes issued by the central administration, all of them date of the time of Qurra b. Ṧarīk, this meaning will be later taken over by term ḫarāğ.

- Poll-tax: the meaning is found in the tax demand notes to individual tax-payers (in which both term gizya and ḥarāğ are employed the first one meaning poll-tax and the second one tax in money that includes the poll-tax), the list and the work permits, in all those documents except the work permit the term found is precisely ğizya al-ra's.

- Land tax: under ğizya al-arḍ.

2. Attestations of term ḫarāğ

a. Type of documents: (NB. Many of those documents are incomplete and consequently we have not been able to identify the type of taxes involved in all the following documents)

There is one estimation of imposition on a village for the land tax in money and in kind (ḫarāğ and ḍarība):

| Document | P.DiemFrüheUrkunden 3 (= PERF 612 = P.Vind.inv. A.P. 6202) |

| Date | ḏu al-ḥiğğā 162/25.8779-18.9.779 |

| Type | Estimation of tax rate for the following year attributed to one village (Taxes to be paid for year 163, document written in ḏu al-ḥiğğā 162) |

| Provenance | Fayyūm |

| Type of tax | Land tax in money and in kind (ḫ arāğ and ḍarība) |

| Amount of taxes | 7 dinars for one year |

| Rate of imposition | Unknown |

| Tax payer | Village of the Fayoum |

| Observation | Explains that the ḫar āğ is imposed according to what is in the registers and the ḍar ība is to be taken from the crops (tadfa ‘u al-ḫarāğ muwazza‘an fī al-ṭubūl wa al-ḍarībata ‘and al-ġala) |

There are four tax demand notes for the land tax in money and/or in kind, those documents take the form of a lease of state land. Those fiscal documents are often precisely dated when complete because they mention the year of imposition and the date of issue of the document as well as the name of the local finance official and of the governor under the authority of which the official is issuing the document.

| Document | P.DiemFrüheUrkunden 05 (= PERF 610 = P.Vind.inv. A.P. 1176 recto and verso) |

| Date | 159-161 A.H./778-779 A.D |

| Type |

Lease of state land issued by Sa’īd b. ‘Ubayd ‘āmil al-amīr Muḥammad b. Sulayman ‘alā kūra Ihnās (unknown governor or finance director?) |

| Provenance | Ihnās |

| Type of tax | Land tax in money and in kind (ḫ arāğ and ḍarība) |

| Amount of taxes | Unknown |

| Rate of imposition | Unknown |

| Tax payer | Unknown |

| Observation | writing exercise? (same document is written twice on each side of the papyrus), fragmentary |

| Document | CPR XXI 02 b (= P.GrohmannAperçu p. 50, P.World p. 116) |

| Date | 176 AH/ 791-2 AD |

| Type |

Lease issued by Ğunāda b. al-Muṣ‘ab ‘āmil al-amīr ‘Umar b. Mihrān ‘alā ḫarāğ kūra al-Fayyūm |

| Provenance | Fayyūm |

| Type of tax | Unknown |

| Amount of taxes | Unknown |

| Rate of imposition | Unknown |

| Tax payer | Ṯubayt mawlā ‘Abd Allah b. ‘Alī |

| Document | P.DiemFrüheUrkunden 04 (= PERF 625 Inv. No.: P.Vind.inv. A.P. 981 verso) |

| Date | 177-178/794-794 |

| Type |

Lease of state land issued by Muḥammad b. ‘Alī ‘āmil al-’amīr Isḥāq b. Sulaymān |

| Provenance | Fayyūm |

| Type of tax | Land tax in money (mentions arḍ naqiyya and payment in dinars) |

| Amount of taxes | 50 dīnar for 50 faddān |

| Rate of imposition | 1 dīnar per faddān |

| Tax payer | Wāḍiḥ mawla ‘amīr al-mu’minin (i.e. most probably al-Rašīd) |

| Observation | From the village of پرپپروره? |

| Document | P.Cair.Arab. 77 |

| Date |

6th of ramaḍān 178 A.H. (5th November 794 A.D.) |

| Type |

Lease of land |

| Provenance | Unknown |

| Type of tax | Land tax in money and in kind (ḫarāğ and ḍarība) |

| Amount of taxes | 12 1/2 faddān for 12 1/2 dīnars |

| Rate of imposition | 1 dīnar per faddān |

| Tax payer | The taxes mentioned here are the ones of year 178 (l.5-6), and the document is written in rama ḍān of the same year |

There are six quittances issued by the ‘amīl ‘alā ḫarāğ kūra kaḏā (the finance administrator of the region of X). Those documents either concern the payment of the poll-tax (ğizya) said to be for the ḫarāğ (i.e. taxes in money) of a certain year or for the land tax (ḫarāğ arḍihi):

| Document | P.David-WeillLouvre 16 |

| Date | Šawwāl 156/25.08-23.09-773 |

| Type |

Quittance for a ḍaman payment issued to a certain Maymūn b. Rāšid. He is paying for the taxes (ḫarāğ) of three individuals through a ḍaman agreement, he pays to the village official (māzūt) Ṧanūda |

| Provenance | Village of Ṭūḫ in the district of al-Bahnasā |

| Type of tax | Impost (ḫarāğ) of year 156 |

| Amount of taxes | 4 dinars |

| Rate of imposition | Unknown |

| Tax payer | Victor and his two sons Humaysa and Zikrī, the payment is made by |

| Document | P.DiemFrüheUrkunden 07 (= P.Vind.inv. A.P. 2704) |

| Date | rabī‘a II 168/21.10.784-20.11.784 |

| Type |

Quittance or tax demand note ? issued by Mūsā b. Muṣ’ab ‘āmil ’amīr al-m’uminīn ‘alā ḫarāğ Miṣr wa ğamī‘ ’amālihā |

| Provenance | Unknown |

| Type of tax | Poll-tax (ğizia ra’sika) |

| Amount of taxes |

Payment of the poll tax of year 168 10 dinars |

| Rate of imposition | Unknown |

| Tax payer | All individuals liable to the poll tax in one kura ? l.8-10 : ‘alā ḫarāği ğamāğimi ’anbāṭ kūra [ ] wa ğawālīhā wa ’anbāṭihā wa ğamī‘ man yaskunuhā min ’ahl al-ḏ imma |

| Document | P.DiemFrüheUrkunden 06 (= PERF 631 P.Vind.inv. A.P.2166) |

| Date | rabi’I 180/ 14.05-13.06.796 |

| Type |

Quittance issued by al-Ṣabāḥ mawlā al-amīr Mūsā b. ‘Īsā (governor 179/796-180/797) wa amīlihi ‘alā kūra al-Fayyūm wa wa ğamī‘ ’amālihā |

| Provenance | Fayyūm |

| Type of tax | Unknown |

| Amount of taxes | Unknown |

| Rate of imposition | Unknown |

| Tax payer | Inhabitant of a village of the Fayyūm |

| Observation | Taxes to be paid for year 179, document written in rabi’I 180 |

| Document |

P.GrohmannProbleme 17 |

| Date | rabi’I 180/ 14.05-13.06.796 |

| Type |

Quittance issued by [al-Ṣabāḥ] mawlā al-amīr Mūsā b. ‘Īsā (governor 179/796-180/797) wa amīlihi ‘alā kūra al-Fayyūm wa wa ğamī‘ ’amālihā |

| Provenance | Fayyūm |

| Type of tax | Unknown |

| Amount of taxes | Unknown |

| Rate of imposition | Unknown |

| Tax payer | Inhabitant of a village of the Fayyūm |

| Observation | Taxes to be paid for year 179, document written in rabi’I 180 |

| Document |

P.Khalili 10 |

| Date | 194 A.H./809-810 |

| Type |

Quittance for land tax |

| Provenance | Unknown |

| Type of tax | Land tax (ḫarāğ arḍihi) of year 19[4] |

| Amount of taxes | 21 dinar and a half and an eighth and half a sixth (ie a twelfth) |

| Rate of imposition | Unknown |

| Tax payer | Riḍa b. Yazīd |

| Observation | Very large amount, this document also might be a passport |

| Document |

P.GrohmannProbleme 18 |

| Date | ramaḍān 196 A.H./ 23.09/20.10.811AD |

| Type | Quittance for the poll-tax with personal description of the taxpayer (passport ?) issued by Yūnis b. ‘Abd al-Raḥman ‘āmil al-amīr ‘Abbād b. Muḥammad (governor 196/812-198/813,) ‘ala ḫarāğ kūra al-Fayūm wa ma‘ūnatiha wa ğamī‘ ’amālihā |

| Provenance | Fayyūm |

| Type of tax | Poll-tax (gizia ra’sika) |

| Amount of taxes | half a dinar (=12 qīrāṭ) for the ḫarāğ of year 195 |

| Rate of imposition | 1/2 for 1 year for one person |

| Tax payer | Aba Qire |

| Observation | Taxes to be paid for year 195, document written in rabi’I 196 |

There is one note on a fiscal document:

| Document |

CPR XXI 02a (= PERF 621, P.GrohmannProbleme III p.143, P.GrohmannAperçu p.85, P.Cair.Arab.II p.70) |

| Date | 176 AH/ 791-2 AD |

| Type | Summery or archival note of a lease or quittance? |

| Provenance | Fayyūm |

| Type of tax | Land tax in money (ḫarāğ) |

| Amount of taxes | 30 dīnars for 40 faddāns |

| Rate of imposition | 3/4 of dinar per faddan |

| Tax payer | Ṯubayt mawlā ‘Abd Allah b. ‘Alī ? |

| Observation | arḍ mu’aṭala (uncultivated land) is not to be included in the ḫarāğ |

There are two letters in which the mention of ḫarāğ is contextual:

| Document |

P.Heid.Arab.II 42 |

| Date | 2nd century |

| Type | Letter concerning a craftsman, mention of ḥarāğ in uncertain and contextual |

| Provenance | Unknown |

| Type of tax | Unknown |

| Amount of taxes | Unknown |

| Rate of imposition | Unknown |

| Tax payer | Craftsman |

| Document |

P.GrohmannProbleme 19 (= PERF 871 P.Vind.inv. A.P. 14908 recto) |

| Date | 2nd-3rd century |

| Type | Letter for the expedition of money from the Fayyūm (not al-Ašmūnayn see verso) to the diwān al-ḫarāğ |

| Provenance | Fayyūm |

| Type of tax | Tax in money (mention of dinar) |

| Amount of taxes | Unknown |

| Rate of imposition | Unknown |

| Tax payer | Inhabitants of the Fayyūm |

b. Meaning attested:

We find ḫarāğ having 3 different meanings in the papyri from the first 200 years of the Islamic calendar:

- Finances: as in the title of officials issuing all fiscal documents ‘amīl ‘alā ḫarāğ kūra kaḏā (the finance administrator of the region of X). Literary sources also attest this general sense for ḫarāğ, as in Fusṭāṭ the diwān al- ḫarāğ was in charge of collecting of the taxes for distribution of the ‘a ṭā to the Muslim community implemented in Egypt.[12] In this case the term ḫarāğ means ‘’finances’’ as in local administrations: ‘āmil ‘alā al-ḫarāğ meaning finance administrator. The amount collected for the taxes paid in money was taken to the diwān al- ḫarāğ (see P.GrohmannProbleme 19) and kept in the provincial treasury (bayt al-māl).

- Tax in money: by association, from the mid-2nd century A.H., ḥarāğ replaced the term ğizya for all tax in money in tax demand notes and quittances for payment of the poll-tax (still precisely ğizya al-ra’s said to be for the ḫarāğ (i.e. taxes in money) of a certain year), or the land tax.

- Land tax in money (earlier example CPR XXI 02 176 AH/ 791-2 AD) under term ḫarāğ alone when mentioned along with ḍariba (the land tax in kind), otherwise under ḫarāğ al-arḍ.

We also learn from this corpus the means of imposition of the land-tax: ḫ arāğ (money tax) was imposed according to what is in the registers and the ḍ arība (tax in kind) to be taken from the crops (tadfa‘u al- ḫ arāğ muwazza‘an fī al- ṭ ubūl wa al- ḍ arībata ‘and al-ġala: P.DiemFrüheUrkunden 3 ḏu al-ḥiğğā 162/779). We also learn that uncultivated land (ar ḍ mu’a ṭ ala) was not liable to ḫ arāğ (CPR XXI 2 176 AH/ 792AD). Only 3 documents from this corpus inform us of the rate for the land-tax in money: it is of 1 dīnar per faddān in two documents and of 3/4 of dinar per faddān in the third one.

Notes

- Simonsen J.B., Studies in the genesis and early development of the caliphal taxation system: with special references to circumstances in the Arab Peninsula, Egypt and Palestine, Copenhagen, 1988, 85-6; P.Lond. IV: xxv-xxxii.

- Grohmman A., ‘‘Aperçu de papyrologie arabe”, Études de papyrology 1 (1932), 70-1; Modarressi, H., Kharāj in Islamic Law, London, 1983 ; for reflection of this change in the papyri see CPR XXI pp.30-31.

- History of the Patriarchs, PO V, 74f; Maqrīzī, Ḫiṭāṭ, I, 99, Abbott N., “A new papyrus and a review of the administration of ‘Ubayd Allah b. al-Ḥabḥab", in Maqdisī Ǧ. Ed., Arabic and Islamic studies in honor of Hamilton A.R. Gibb, Leiden, 1965, 21-35.

- Modarressi op.cit.: 88-9.

- Out of 32 documents published by G. Khan from early Islamic Khurasan, 20 mention ḫarāğ and they date between 138/775 and 160/777: Khan G., Arabic Documents from early Islamic Khurasan, London, 2007.

- P.Cair.Arab. III.180.

- Document to be published by Khaled Younes.

- P.DiemFrüheUrkunden 07.

- P.GrohmannProbleme 18.

- P.GrohmannProbleme 05.

- Raġib Y., “Sauf-conduits d’Égypte Omeyyade et Abbasside”, AnIsl 31 (1997), 143-158; Diem W., “Einige frühe amtliche Urkunden aus der Sammlung Papyrus Erzherzog Rainer (Wien)”, Le Muséon 97 (1984) 109-158 (document 8 and 9); P.Cair.Arab.III 174, 175.

- Bouderbala S., Ğund Miṣr: Etude de l’administration militaire dans l’Égypte des débuts de l’Islam 21/642 – 218/833, PhD dissertation, Paris, 2008, 180-183.

J. Bruning

version 26.4.2012

Abbreviations follow the Checklist of published Arabic documents and abbreviated references to books or articles refer to the publications listed here.

A

Aǧal: ‘term’.

- pap.: P.Qurra 4; Becker (1911), no. 3

Aǧǧala: ‘to set a term for payment’.

- pap.: P.Qurra 4

Ahl al-qabāla: term found in fiscal overviews designating tenants of agricultural land. See also s.v. ‘qabāla’.

- pap.: P.Mil.Vogl. Arab 7.

Aḫraǧa: see s.v. ‘istaḫraǧa’.

ʽAlā: ‘on (the land of)’.

- bibl.: Diem (2006), 56

‛Amāra: ‘assessment’. In some documents the term is replaced by the term ḫarāǧ (q.v.).

‛Āmil: fiscal administrator. The Arabic ‛āmil is the origin of the Greek ἀμαλίτης. In P.Lond. IV 1359, the Arabic ‛ummāl corresponds to the Greek ὑπουργοὶ.

- pap.: Abū Ṣafiyya 11; CPR XVI 7; P.Cair.Arab. III 175; P.World, 171-2; Sijpesteijn (2011).

- bibl.: commentary to P.Cair.Arab. III 175; Gonis (2004), 190

Aṣāba (IV): ‘to fall upon’, ‘to be liable to’.

- pap.: P.Cair.Arab. III 180

‛Āšir: someone who collects the tithe (Ar. ‛ušr).

- pap.: P.Heid.Arab. II 6

B

Bāb (pl. abwāb): a term meaning ‘category’. The term often occurs together with al-ḫarāǧ, “the fisc and (its) categories”, or in the form abwāb al-māl, “different kinds of tax money” (Abū Ṣafiyya 13.4). Among the latter were aḫmās al-madā’in (a fifth levied on the revenues of mines) and aḫmās al-ġanā’im (a fifth levied on booty).

- pap.: P.Cair.Arab. III 146; Abū Ṣafiyya 13, 27; Sijpesteijn (2011).

Bāqī : the ‘remainder’ of tax money that still needs to be paid.

- pap.: cf. P.Heid.Arab. I 2; Grohmann (1938): bāqiyat al-ḥisāba

Baqṭ (C. and Gr. πάκτον): a term meaning “holding” or “rent”. It formed a land tax lower that the ḫarāǧ to be paid, mostly at the value of a tithe, for working a monastery’s land. See also s.v. , ‛ušr’.

- pap.: CPR XXI 7; Grohmann (1938), l. 2: baqṭ al-Qibṭ; P.Philad.Arab. 7

- bibl.: Frantz-Murphy (2001), 186; Morimoto (1981), 184-6; Clackson (2000), 18-20

Barā’a: a document, often translated as ‘quittance’, that proved payment of (part of) the taxes. The document was not limited to use within a fiscal context but can also be found within, e.g., commercial spheres.

- bibl.: Hussein, 141.

Bayt al-māl: the ‘treasury’ (Gr. σάκελλα). An employee of the treasury was called a ḫāzin (pl. ḫuzzān). P.Vindob. G 31 mentions a αὐλὴ τοῦ δημοσίου, which may have been a building other than the bayt al-māl related to the fiscal administration.

- pap.: Abū Ṣafiyya 16, 41; Diem (1984) 3, 4; P.Cair.Arab. II 95, III 149

- bibl.: Bell (1910), 80-1; Cahen (1960); Morelli (1998), 183-6.

Buq‛a: ‘a plot of land’.

D (D, Ḍ)

Daf‛a: a term designating ‘amount’ or ‘payment’ that often introduces documents related to taxation and sums up the amount of money to be paid. A different but seemingly erroneous interpretation of the word is ruq‛a, ‘page’.

- bibl.: Diem (2006), 56; Frantz-Murphy (2001), 126-8.

Ḍarībat (aṭ-ṭaʽām): ‘tax on crops’, part of the public taxes and paid in kind (with ṭa‛ām in the meaning of wheat or food in general; Gr. ἐμβολή σίτου or αἰσια ἐμβολή). Sometimes the term ḫarāǧ is used in a similar sense. In fiscal receipts or leases the term ḍarība does not occur after 182/798. In Greek papyri, the term ἐμβολάρχης stands for an administrative official related to the levying of the tax on crops. The expences for the transport of grain fell on the tax payers and were called ναῦλον ἐμβολῆς.

- pap.: Becker (1907), no. 16; CPR XXI 1, 3, 4, 5; Diem (1984a), nos 3 and 5; P.Cair.Arab. III 160, IV 286; P.Philad.Arab. 7; P.Heid.Arab. I 5, 9, appendix a, c, e, g, k, l

- bibl.: Abū Ṣafiyya, 90-1; Bell (1910), xxv-vi; Foss, 259-60; Frantz-Murphey (2001), 145-6; Hussein, 98-9.

F

Fuḍūl: ‘extraordinary taxes’ (Gr. ἐκστραόρδινα, also διανομαί is found), meant to cover State expences. Abū Ṣafiyya interprets fuḍūl (‘remainders’; Ar. sg. faḍ l or faḍ la) as the Arabic term for the extraordinary taxes. The word fuḍūl is used in juxtaposition with ‘māl’ (s.v.).

- pap.: Chrest.Khoury I 66: fuḍūl arḍika; Grohmann (1938); Sijpesteijn (2011).

- bibl.: Bell (1910), xxvi, xxix; Abū Ṣafiyya, 94

G (Ǧ, Ġ)

Ǧabā: ‘to collect’.

- pap.: P.Heid.Arab. I 1

Ǧāliya (pl. ǧawālī; Gr. pl. φυγάδες): a ‘fugitive’ who fled from his home village to another in order to escape taxation after the communal responsibility of the fiscal system was changed into a personal responsibility in the second half of the 2nd/8th century. In order to restrain people from fleeing, the administration oblidged the possession of work permits when people wished to leave their village. Greek texts mention a ἐπικείμενος τῶν φυγάδων, ‘commisioner of the fugitives’, who stood in direct contact with the governor. From the late 220s/840s the term ǧāliya seems to have replaced ǧizya in the meaning of poll tax; cf. Grohmann, “Probleme” II 7.

- pap.: Diem (1984a) 7; Grohmann, “Probleme”, II/3, no. 7; P.Berl.Arab. I 1; P.Cair.Arab. III 151; P.Heid.Arab. I 12; Rāġib (1981), no. 2

- bibl.: Abū Ṣafiyya, 88-9; Becker (1911), 367ff.; Cahen (1965a); Cahen (1965b), 561; Christides (1993), 73; Frantz-Murphy (1999), 245ff.; ibid. (2001), 143, 146.

Ġarāma (pl. ġarāmāt): a seldom-occurring financial term meaning ‘a fine’ often mentioned together with the abwāb (see s.v. ‘bāb’) and fuḍūl (q.v.).

- bibl.: Abū Ṣafiyya, 96-7.

Ǧibāya: ‘land survey’.

- pap.: Abbott (1965); P.Ryl.Arab. I § II 8, 9; P.World, 130-2

Ǧizya 1: used for the entire category of ‘money tax’ until 156/773 (after this date ḫarāǧwas used).

- pap.: P.Cair.Arab. III 149, 169: ǧizyat kūratika, 153, 160, 161-3, 174, 175, 180; P.World, 133: ǧazāyat Miṣr; Diem (1984a), no. 8; P.Heid.Arab. I 1, 5, 6, appendix a-l; Becker (1911), no. 3: ǧizyat kūratikā; Sijpesteijn (2011).

- bibl.: Bell (1910), xxv, xxvii; Frantz-Murphy (1999), 247; ibid. (2001), 141; Clackson (2000), 24-6; Cahen (1965b).

Ǧizya 2: ‘poll tax’ (Gr. ἀνδρισμός or διάγραφον). Also the terms ǧizyat ar-ra’s occurs (and from the late 220s/840s ǧāliya).

- pap.: Diem (1984a) 7; Grohmann, “Probleme”, II/3, nos 5, 6, 7, 18; P.Cair.Arab. III 180; P.Gen.Arab. 1; Rāġib, “Sauf-conduits”, nos. 1, 5-8; see also s.v. ‘ǧizya 1’

- bibl.: Bell (1910), xxv, xxvii; Frantz-Murphy (1999), 247; ibid. (2001), 141; Clackson (2000), 24-6; Gonis (2003), 150.

Ǧizyat al-arḍ: ‘land tax’, cf. s.v. ‘ḫarāǧ 1 and 2’.

H (Ḥ, Ḫ)

Ḫāliṣ: a heading in fiscal overviews denoting the remainder.

- pap.: Grohmann (1938)

Ḥaqq: ‘right’ in the sense of a legal claim or asset. Already in the Qurra papyri the expression ḥaqq amīr al-mu’minīn, ‘that to which the caliph is entitled’, is found. In later documents ḥaqq is used as part of ḫarāǧ (q.v.).

- pap.: Sijpesteijn (2011).

- bibl.: Cohen (1960), 1142a-b; Frantz-Murphy (2001), 153-4.

Ḫarāǧ 1: ‘taxes’ in general; ‘money tax’ or ‘public tax’ (Gr. (τὰ χρυσικὰ) δημόσια) after 156/773 (see also s.v. ‘ǧizya’), which was divided into a land tax, poll tax (s.v. ‘ǧizya’) and the extraordinary taxes (s.v. ‘fuḍūl’); ‘land tax’ (s.v. ‘ḫarāǧ 2’).

-pap.: CPR XXI 1, 2.b, 3, 5, 6, 7; David-Weill (1971), no. 16; Diem (1984), nos 3, 5, 7, 10; Grohmann, “Probleme”, II, nos 7, 17, 18; Muġāwirī, Alqāb, III, nos 19, 22; P.Cair.Arab. 77; P.Heid.Arab. II 42

- bibl.: Abū Ṣafiyya, 83-8; Bosworth, 130; Frantz-Murphy (2001), 141-3

Ḫarāǧ 2: ‘land tax’ (Gr. δημόσια γῆς or simply δημόσια). Also ḫarāǧ al-arḍ is attested. This tax was countered by a trade tax (Ar. maks, s.v.), which was to be paid by non-land holding merchants.

- pap.: P.Gen.Arab. 1; P.Khalili I 10

- bibl.: Abū Ṣafiyya, 91-3; Bell (1910), xxv, 222; P.Heid.Arab. I pp. 51-6.

Ḫarāǧ al-arḍ: see s.v. ‘ḫarāǧ 2’.

Ḫarāǧ al-ǧamāǧim: probably similar to ǧizyat ar-raʼs, ‘poll tax’.

- pap.: Diem (1984a) 7

Ḥāṣil: either the receipts in the treasury or the amount of tax money expected from the tax collector.

Ḫusr: either a ‘loss’ or a ‘deduction’ in the final state of the tax quota.

- bibl.: Frantz-Murphey (2001), 151.

I

Intaqala (VIII): verb occuring in tax lists indicating that someone listed lives in another village. Perhaps identical to ittaǧaha (s.v.).

- pap.: PER inv. Ar. Pap. 3136

Istaḫraǧa (X): verb meaning ‘to levy’. Also aḫraǧa occurs. A mustaḫriǧ occurs in P.Heid.Arab. II 6.

- pap.: Abū Ṣafiyya 11; P.Heid.Arab. I 10, 11; Sijpesteijn (2011).

- bibl.: Diem (1983), 108-9.

Ittaǧaha (VIII): verb occuring in tax lists indicating that someone listed lives in another village. Perhaps identical to intaqala (s.v.).

- pap.: P.Cair.Arab. III 203

K

Kirā’: a type of tenancy based on a fixed rent. The term (or its root) is found in agricultural leases up to 272/885.

- bibl.: Frantz-Murphy (2001), 152; Løkkegaard, 175.

M

Maks: a kind of money tax levied on merchants as a counterpart of the land tax (s.v. ‘ḫarāǧ 2’).

- pap.: Becker (1911) 4; P.Cair.Arab. I 6

- bibl.: Abū Ṣafiyya, 91-3; Bell (1910), xxv, 222; P.Heid.Arab I pp. 51-6;

Māl: taxes in general, in contrast to the ‘fuḍūl’ (s.v.), extraordinary taxes.

- pap.: Abū Ṣafiyya 13; Sijpesteijn (2011).

- bibl.: Sijpesteijn (2011), p. 266.

Māzūt (pl. mawāzīt; Gr. μειζότερος): term of Greek origin meaning ‘village chief’. Abū Ṣafiyya (146-51) argues that the word should be read as mārūt and that it has a semitic origin.

- pap.: David-Weill (1971) 16; P.Cair.Arab. III 149, 158; P.Heid.Arab. I 8;

- bibl.: Abū Ṣafiyya, 146-151; Frantz-Murphy (2001);

Misāḥa: ‘cadastre’.

- pap.: P.Khalili I 2

Mu’na (also ma’ūna is found, pl. mu’an; Gr. δαπάνη): a term indicating provisions for officials. It may have been similar to, related to, or part of, the δαπάνη (s.v. ‘nafaqa’) and rizq (q.v.).

- bibl.: Frantz-Murphey (2001), 154-5; Løkkegaard, 186-7.

Muta‛aṭṭala: term found in fiscal overviews designating uncultivated land.

- pap.: CPR XXI 2.a

N

Nafaqa: ‘expenditure’, used to designate the money needed to pay for the sustenance of travelling soldiers or officials.

- pap.: Grohmann, “Aperçu”, 41, 44, 45; P.Heid.Arab. I 7

- bibl.: Bosworth, 136; Hussein, 76-81.

Naffaḏa (II): ‘to enforce’, ‘to put into effect’.

- pap.: Abū Ṣafiyya 11

Naǧm (pl. nuǧūm): ‘installment’. See also s.v. ‘ṭabl’.

- pap.: Chrest.Khoury I 65, 66; CPR XVI 5.b; CPR XXI 4;

- bibl.: Frantz-Murphy (2001)

Naḫl: tax on date palms.

- pap.: Grohmann, “Probleme” II 7

Naqṣ: translated by Grohmann as ‘Abgängen’.

- pap.: Grohmann, “Probleme” 5

Nawā’ib: a term that is only found in the plural. Its singular may have been nā’iba, literally meaning ‘misfortune’ and hence used for the expences for repairing canals, bridges, and dams that fell on the landholders and was to be paid in addition to the ḫarāǧ (q.v.) and ḍarība (q.v.). Gladys Frantz-Murphy translates it with ‘canal and dam assessments’. The term may be an arabised form of the Greek ναύβιον, which was derived from a ancient-Egyptian term nb. The term appears in dated Arabic documents from 169/785 to 275/887. Løkkegaard interprets the nawā’ib as expenditure for the conveyance and guidance of military and administrative officials.

- pap.: CPR XXI 1, 6; P.Ryl.Arab I § II 7; Loth (1880) (cf. Diem, “‛Ammār”, p. 257, n. 16)

- bibl.: Frantz-Murphy (2001), 155-6; Løkkegaard, 186-7.

Q

Qabāla: ‘tenancy’. Diem ((2006), 56) translates qabālat N.N. as ‘in der Steuerpachtung von N.N.’.

Qabbāl (pl. qabbālūn): a ‘collector’ who collects the tax on crops in the villages and brings it to the granaries in al-Fusṭāṭ. In one papyrus from the Qurra corpus (Diem (1984), 263 (line 2); cf. Abū Ṣafiyya 17.2), the term qabbāl aḏ-ḏahab occurs. If this reading is correct, the term may have been used as an equivalent to qusṭāl (q.v.).

- pap.: P.Cair.Arab. III 169; P.Heid.Arab. I 3

- bibl.: Hussein, 122; Frantz-Murphey (2001), 50.

Qassama (II): ‘to assign’ an amount of tax money.

- pap.: Abū Ṣafiyya 11

Qayyada (II): translated by Grohmann as ‘to amount to’ (?).

- pap.: Grohmann, “Probleme” II 5

Qudūma: it is not known whether qudūma is the beginning of phrase (rendered in Greek by τ(ῆς) καθ(ό)δ(ου)) or has a technical meaning (rendered in Greek as περὶ τ(ῆς) καθ(ό)δ(ου) αὐτ(οῦ) μ(ετὰ) χρυσικ(ῶν) δημ(οσίων)).

- pap.: Cadell (1967) 1.1

Qusṭāl: also written as ǧusṭāl, the collector of money taxes. The oldest attestation of this collector is in one of the Qurra papyri. In later times the term ǧahbad (pl. ǧahābida) became used instead of qusṭāl. In contrast to the qabbāl (q.v.), who was chosen at a village level, the qusṭāl collected the money taxes due from an entire kūra. See also s.v. ‘qabbāl’.

- pap.: Abū Ṣafiyya 37; P.Cair.Arab. III 149, IV 285

- bibl.: Hussein, 120-1.

R

Rasm (pl. rusūm): a term used for a register or administrative overview of the kūras within one administrative unit. In this sense it may be interchangeable with the term ǧadwal, ‘table’. In another sense, it may indicate a schedule of rates.

- bibl.: Frantz-Murphey (2001), 113-4; Løkkegaard, 90.

Rizq (Gr. ῥουζικόν, ῥογά): a charge on non-Muslims for the maintenance of Muslim soldiers and administrative officials. The maintenance of soldiers was paid out of the tax on crops (q.v.). In Egypt, the terms ḍiyāfa, nuzl, and qirā seem to have had the same meaning as rizq.

- pap.: Abbott (1965); Abū Ṣafiyya 2, 11, 38; P.Heid.Arab. I 3, 13;

- bibl.: Bell (1910), xxv; Hussein, 52; Løkkegaard, 186; Mayerson (1994) and (1995);

S (S, Š, Ṣ)

Ṣadaqa (also ‛ušr, and zakā): all three Arabic terms in general, and especially as concerns the fisc, were used in similarly meaning a tax that levied to be distributed among the poor (Ar. fuqarā’) and the needy (Ar. miskīn). The fixing of the poor tax per province is called ‛ibra in legal literature. The existence of an overseer of the distribution of the poor tax, called ṣāḥib aṣ-ṣadaqa, is attested in papyri from the early 2nd/8th c. onwards.

- pap.: Grohmann, “Probleme” II 7

- bibl.: Becker (1913); Frantz-Murphy (2001), 143; P.Khalili I, p. 52ff.; Hussein, 126, 141;

Ṣāḥib al-ḫarāǧ: the highest administrative post under the governor related to taxation. In literary sources also the term wālī al-ḫarāǧ is used.

Ṣāḥib al-maks: an official supervising the taxes levied on merchants (s.v. ‘maks’)

- pap.: P.Heid.Arab. I 2

Sammāk (pl. samāmika; Gr. σύμμαχος): an administrative official involved in collecting taxes.

- pap.: Sijpesteijn (forthcoming), nos. 14, 15.

- bibl.: Sijpesteijn (forthcoming), 206.

Ṣarf: a heading found in some fiscal overviews under which was indicated whether or not the tax payer was given a discount.

- bibl.: Becker (1913); Frantz-Murphey (2001), 146-50.

Siǧill: ‘register’; see also s.v. ‘tasaǧǧala’.

pap.: CPR XXI 7

T (T, Ṯ, Ṭ)

Ṭabl (pl. ṭubūl): a term on which there is no agreement as to its exact meaning but used in two contexts. Frantz-Murphey interprets ṭabl on the basis of Arabic papyri dating from before 190/805 as ‘register’. Its equivalent in Greek papyri would be κατάγραφον. According to Dennett, such a document was used to establish the tax quota. From 212/827 ṭabl was replaced by siǧill in the same meaning.

- pap.: Chrest.Khoury I 66; CPR XXI 3, 4, 6; Diem (1984) 3; Grohmann, “Probleme”, II/3, no. 5; Grohmann (1938); P.Berl.Arab. II 24; P.Cair.Arab. III 169

- bibl.: Dennett, 97; Frantz-Murphey (2001), 111-4; cf. Løkkegaard, 108

Ṯaman: also ṯaman aṣ-ṣuḥuf or ṯaman al-barā’a; a small amount of money (often 1/48 dinar) to be paid by the tax payer for drafting a receipt. This money may be counted among the ǧizya (as in P.Cair.Arab. III 180). - pap.: P.Cair.Arab. III 180; P.Philad.Arab. 23

- bibl.: commentary to P.Cair.Arab. III 181.8-9; Grohmann, “Probleme”, II, 147

Ta’rīǧ (easily misread as ta’rīḫ): the name used for a document stating the difference between the estimated assessment made in spring and the actual assessment in autumn. It was also used for the difference itself.

- bibl.: Frantz-Murphy (2001), 156-7.

Tasaǧǧala (V): ‘to register’ in a register (Ar. siǧill).

- pap.: P.Ryl.Arab. I § I 5; P.World, 171-2

Ṭasq: the tax quota levied on various sorts crops.

- bibl.: Løkkegaard, 125-6.

Tawzī‛: the ‘apportionment’ of fiscal levies.

- pap.: CPR XXI 3, 5

U

‛Ušr: there are two different taxes called ‛ušr, ‘tithe’. The first is a tax levied on the lands of Muslim converts. Until the time of the Abbasid caliph al-Mahdī (r. 158/775-169/785) Muslims paid ‛ušr, after that time they were levied ḫarā ǧ (q.v.). The second kind of tithe is the ἀπαρχή, a rent tax (also called pactum (see s.v. ‘baqṭ’) or dēmosion) levied by monasteries on individuals who worked land in possession of the monastery. Monasteries collected this rent for the payment of their own taxes.

- pap.: Grohmann, “Probleme” II 7

- bibl.: Becker (1905); Clackson (2000), 18-22, 24

W

Wafr: surplus.

- pap.: Sijpesteijn (2011).

Z (Z, Ẓ)

Zimām: an office possibly for controlling the fisc.

- pap.: K. Younes, ‘New governors identified in Arabic papyri,’ In M. Legendre and A. Delattre (eds.), Authority and control in the countryside: Late Antiquity and Early Islam: Continuity and Change in the Mediterranean 6th-10th century I, (forthcoming) [= P.Ryl.Arab I § I 5]

- bib.: "Zimām" in EI, 2nd ed., XI, p. 509a

K. Younes & J. Bruning

version 8.5.2012

The information given in the third column is classified as follows:

1 = references to papyri (the abbreviations follow The Checklist of Arabic documents); and

2 = references to exagia (for bibliographical references, see below). Note that most governors mentioned in exagia are mentioned in their capacity of financial directors.

* = not in al-Kindī’s Kitāb al-wulāt wa-l-quḍāt

Rāshidūn caliphate

|

Governors

|

Period of office

|

Attestation(s) in papyri and exagia

|

|

'Amr b. al-'Āṣ (1st) |

21-25/641-645 |

|

|

'Abdallāh b. Sa'd |

25-35/645-655 |

|

|

Muḥammad b. Abī Ḥudhayfa |

35-36/656-657 |

|

|

Qays b. Sa'd |

37/657 |

|

|

Mālik b. al-Ḥārith al-Ashtar |

37/657 |

|

|

Muḥammad b. Abī Bakr |

37-38/658 |

Umayyad caliphate

|

Governors

|

Period of office

|

Attestation(s) in papyri and exagia

|

|

'Amr b. al-'Āṣ (2nd) |

38-43/658-664 |

|

|

'Utba b. Abī Sufyān |

43-44/664-665 |

|

|

'Uqba b. 'Amir |

45-47/665-667 |

|

|

Maslama b. Mukhallad |

47-62/667-682 |

|

|

Sa'īd b. Yazīd |

62-64/682-684 |

|

|

'Abd al-Raḥmān b. 'Utba |

64-65/684-685 |

|

|

'Abd al-'Azīz b. Marwān |

65-86/685-705 |

1 PERF 582 r; PERF 583 r =[Diem (1984) 1, 2] |

|

'Abdallāh b. 'Abd al-Malik |

86-90/705-708 |

1 P.Cair.Arab. I 12, 13; CPR III 31, 32, 34, 35, 36, 37 |

|

Qurra b. Sharīk |

90-96/709-714 |

1 CPR III 64; P.Cair.Arab. I 14 =[Chrest. Khoury I 3]; P.Cair.Arab. ІІІ 146-163 [146 = Becker (1911) 1, 147 = Becker (1911) 4 & Becker (1906) 7, 148 = Becker (1911) 2, 149= Becker (1911) 3, 150 = Becker (1906)12, 151= Becker (1911) 5 & Becker (1906) 14, 152 = Becker (1911) 10, 153= Becker (1911) 6 & Becker (1906) 13, 154 = Becker (1911) 8, 155 = Becker (1911) 9, 156 = Becker (1911) 11, 160 = Becker (1911) 13, 161 = Becker (1911) 14, 162 = |

|

'Abd al-Malik b. Rifā'a (1st) |

96-99/714-717

|

1 CPR III 65 |

|

Ayyūb b. Shuraḥbīl |

99-101/717-720

|

|

|

Bishr b. Ṣafwān |

101-102/720-721 |

|

|

Ḥanẓala b. Ṣafwān (1st) |

102-105/721-724 |

|

|

Muḥammad b. 'Abd al- Malik |

105/724 |

|

|

al-Ḥurr b. Yūsuf

|

105-108/724-727 |

|

|

Ḥafṣ b. al-Walīd (1st) |

108/727 |

2 Balog (1976), nos 124-34 |

| 'Abd al-Malik b. Rifā'a (2nd) |

109/727 |

|

|

al-Walīd b. Rifā'a |

109-117/727-735 |

|

|

'Abd al-Raḥmān b. Khālid |

117-118/735-736 |

|

|

Ḥanẓala b. Ṣafwān (2nd) |

119-124/737-742 |

|

|

Ḥafṣ b. al-Walīd (2nd) |

124-127/742-744 |

1 CPR III 114, 115 |

|

Ḥassān b. 'Atāhiyya |

127/745 |

|

|

Ḥafṣ b. al-Walīd (3rd) |

127-128/745 |

|

|

al-Ḥawthara b. Suhayl |

128-131/745-748 |

|

|

al-Mughīra b. 'Ubaydallāh |

131-132/748-749 |

1 CPR III 119 |

| 'Abd al-Malik b. Marwān | 132/750 | 1 131/749: P. Ryl. Arab. I § IV 5 ???: P. Heid. Arab. Inv. 550 r 2 Balog (1976), nos 256-70 |

Abbasid caliphate

|

Governors

|

Period in office

|

Attestation(s) in papyri and exagia

|

|

Ṣāliḥ b. 'Alī (1st) |

133/750-751 |

2 Balog (1976), nos 293-301 |

|

'Abd al-Malik b. Yazīd [Abū 'Awn] (1st) |

133-136/751-753 |

1 CPR III 120, 121, 123; P.Ryl.Arab. I IV 1, 2, 4, 5 [Raghib (1992) 2, 3, 4, 5]; Diem (1989) 1; Raghib (1997) 5, 6, 7, 8; Raghib (1978) 1=[Chrest. Khoury I 95]; P.Cair.Arab. III 169; P.Heid.Arab. Inv. 550 r (publication in progress)

|

|

Ṣāliḥ b. 'Alī (2nd) |

136-137/753-775 |

2 see above |

|

'Abd al-Malik b. Yazīd [Abū 'Awn] (2nd) |

137-141/754-758 |

2 see above |

|

Mūsā b. Ka'b |

141/758-759 |

1 141/758: Hinds & Sakkout (1981) |

|

Muḥammad b. al-Ash'ath |

141-143/769-760 |

1 CPR III 125, 126; P.Cair.Arab. VII 445 |

|

Ḥumayd b. Qaḥṭaba |

143/760-762 |

2 Balog (1976), nos 408-14; Eldada (2002), nos 25 and 26 |

|

Yazīd b. Ḥātim |

144-152/762-769 |

1 P.Cair.Arab. III 197 |

|

'Abdallāh b. 'Abd al-Raḥmān |

152-155/769-772 |

|

|

Muḥammad b. 'Abd al-Raḥmān |

155/772 |

|

|

Mūsā b. 'Ulayy |

155-161/772-778 |

|

|

* Muḥammad b. Sulaymān |

159-161/778-779 |

1 PERF. 610 r & v = [Diem (1984) 5]; CPR III 130 |

|

'Isā b. Luqmān |

161-162/778-779 |

2 Balog (1976), nos 5538 (see also no. 514) |

|

Wāḍiḥ |

162/779 |

1 CPR III 133 |

|

Manṣūr b. Yazīd |

162/779 |

|

|

Yaḥyā b. Dāwūd [Abū Ṣāliḥ] |

162-164/779-780 |

1 CPR III 134, 135 |

|

Sālim b. Sawāda |

164/780-781 |

|

|

Ibrāhīm b. Ṣāliḥ (1st) |

165-167/781-784 |

1 CPR III 137, 138; P. Terminkauf 2 |

|

Mūsā b. Muṣ'ab |

167-168/785 |

1 Diem (1984) 7

2 Balog (1976), no. 578 |

|

'Asāma b. 'Amr |

168/785 |

|

|

al-Faḍl b. Ṣāliḥ |

169/785-786 |

1 CPR III 139 |

|

'Alī b. Sulaymān |

169-171/786-787 |

1 CPR III 140 |

|

Mūsā b. 'Isā (1st) |

171-172/787-789 |

2 Balog (1976), nos 587-90 |

|

Maslama b. Yaḥyā |

172-173/789 |

|

|

Muḥammad b. Zuhayr |

173/789-790 |

1 CPR III 144 |

|

Dāwūd b. Yazīd |

174-175/790-791 |

|

|

Mūsā b. 'Isā (2nd) |

175-176/791-792 |

|

|

* 'Umar b. Mihrān |

176/791 |

1 PERF 621=[P. World p. 116-119; CPR XXI 2] |

|

Ibrāhīm b. Ṣāliḥ (2nd) |

176/792 |

|

|

'Abdallāh b. al-Musayyab |

176-177/792-793 |

1 PERF 624 =[P. world p. 132-134] |

|

Isḥāq b. Sulaymān |

177-178/793-794 |

1 PERF 625 =[Diem (1984) 4] |

|

Harthama b. A'yān |

178/794 |

|

|

'Abd al-Malik b. Ṣāliḥ |

178/794-795 |

|

|

'Ubaydallāh b. al-Mahdī |

179/795 |

1 CPR III 146 |

|

Mūsā b. 'Isā (3rd) |

179-180/765-796 |

1 PERF 631 =[Diem (1984) 6]; PERF 638 =[Chrest. Khoury II 26; CPR XXI 4] |

|

'Ubaydallāh b. al-Mahdī (2nd) |

180-181/796-797 |

|

|

* Ḥuwayy b. Ḥuwayy |

181-182/797-798 |

1 P.Ryl.Arab I I 5 [= P.World, 171-2]; Khaled Younes, ‘New governors identified in Arabic papyri,’ In M. Legendre and A. Delattre (eds.), Authority and control in the countryside: Late Antiquity and Early Islam: Continuity and Change in the Mediterranean 6th-10th century I, (forthcoming) |

|

Ismā'īl b. Ṣāliḥ |

181-182/797-798 |

|

|

Ismā'īl b. 'Īsā |

182/798 |

|

|

al-Layth b. al-Faḍl |

182-187/799-802 |

1 P.Ryl Arab. I IX 6 [= CPR XXI 5] |

|

Aḥmad b. Ismā'īl |

187-189/803-805 |

|

|

'Ubaydallāh b. Muḥammad (Ibn Zaynab) |

189-190/805-806 |

2 Balog (1976), nos 631-2 |

|

al-Ḥusayn b. Jamīl |

190-192/806-808 |

2 Balog (1976), nos 635, 639 |

|

Mālik b. Dalham |

192-193/808 |

2 Balog (1976), nos 636-9 |

|

al-Ḥassan b. al-Takhtāḥ/kh |

193-194/808-809 |

1 P.Heid.Arab. Inv. 539 r |

|

Ḥātim b. Harthama |

194-195/809-811 |

|

|

Jābir b. al-Ash'ath |

195-196/811-812 |

2 Balog (1976), no. 646 |

|

'Abbād b. Muḥammad |

196-198/812-813 |

1 PERF 670 [= Grohmann, (1934) 18] |

|

al-Muṭṭalib b. 'Abdallāh (1st) |

198/813-814 |

|

|

al-'Abbās b. Mūsā |

198-199/814 |

2 Balog (1976), no. 647 |

| al-Muṭṭalib b. 'Abdallāh (2nd) | 199-200/814-816 | 1 CPR III 148 2 Balog (1976), nos 649-50 |

| al-Sarī b. al-Ḥakam | 200-201/816 | 1 CPR III 149 |

References (for exagia)

- P. Balog, Umayyad, 'Abbāsid and Ṭūlūnid glass weights and vessel stamps, New York: American Numismatic Society, 1976

- K. Eldada, “Glass weights and vessel stamps”, in J.L. Bacharach (ed.), Fustat finds: beads, coins, medical instruments, textiles, and other artifacts from the Awad collection, Cairo/New York: The American University in Cairo Press, 2002, pp. 112-66.

1. State formation

1.1. Some medieval but important literary sources

- Al-Kindī (d. 350/961), Kitāb al-wulāt wa kitāb al-quḍāt, ed. R. Guest, The Governors and Judges of Egypt, Leiden 1912.

- Ibn ‘Abd al-Ḥakam (d. 257/871), Futūḥ miṣr wa-akhbaruhā, ed. Ch. Torrey, the History of the Conquests of Egypt, Leiden 1920.

- Ibn al-Kindī (d. ca. 360/970), Faḍā’il Miṣr, eds. I. A. al-‘Adawī and ‘A. M. ‘Umar, Cairo 1971.

- Ibn Yūnus (d. 347/958), Tārīkh Ibn Yūnus al-Miṣrī, ed. ‘A Fatḥī, 2 vols, Beirut 2000.

- Ibn Zulāq (d. 387/997), Faḍā’il miṣr wa-aḫbāruhā, ed. ‘A.M. ‘Umar, Cairo 2000.

1.2. Secondary sources

- Athamina K., “Arab settlement during the Umayyad caliphate”, JSAI 8, (1986), 185-207.

- ‘Umar A. M., Ta’rīḫ al-luġa al-‘arabiyya fī Maṣr, Cairo, 1970.

- Bell H. I., “The administration of Egypt under the Umayyad Khalifs”, Byzantinische Zeitschrift 28, (1928), 278-286.

- Butler A. J., The Arab conquest of Egypt and the last thirty years of the Roman dominion, Oxford, 1978.

- Carrié J-M., “Séparation ou cumul Pouvoir civil et autorité militaire dans les provinces d’Egypte de Gallien à la conquête arabe”, Les gouverneurs de Province dans l’Antiquité tardive, Antiquité tardive 6, Turnhout, 1998, 105-121.

- Christides V., “Nubia and Egypt from the Arab invasion of Egypt until the end of the Umayyads”, In Ch. Bonnet ed., Études Nubiennes, Actes du VIIe Congrès International d’Études Nubiennes 3–8, (1992), 341–56.

- Donner, F., The early Islamic conquests, Princeton, 1981.

- Donner, F., “The formation of the Islamic state”, Journal of the American oriental society 106, (1986), 283-296.

- Foss C., “Egypt under Mu‘āwiya: Part I: Flavius Papas and upper Egypt”, Bulletin of SOAS 72, (2009), 1-24.

- Foss C., “Egypt under Mu‘āwiya: Part II: Middle Egypt, Fusṭāṭ and Alexandria”, Bulletin of SOAS 72, (2009), 259-278.

- Grohmann A., “Der Beamtenstab der arabischen Finanzerwaltung in Ägypten in früh Islamischer Zeit”, Studien zur Papyrologie und antiken Wirtschaftsgeschichte, Friedrich Oertel zum achtzigsten Geburtstag gewidmet, Bonn, 1924, 120-134.

- Kaegi W., “Egypt on the eve of the Muslim conquest”, in C.F. Petry ed., The Cambridge History of Egypt. I Islamic Egypt, 640-1517, Cambridge,1998, 34-61.

- Kennedy H., “Central government and provincial élites in the early ‘Abbasid Caliphate,” BSOAS 44, (1981), 26-38.

- Kennedy H., “Egypt as a province in the Islamic Caliphate”, in C. F. Petry ed., the Cambridge history of Egypt. I Islamic Egypt, 640-1517, Cambridge, 1998, 62-85.

- Lane-Poole S., History of Egypt in the middle ages, London, 1925.

- Lev, Y., “Regime, Army and Society in Medieval Egypt, 9th-12th Centuries”, in Y. Lev ed., War and Society in the Eastern Mediterranean, 7th-15th Centuries, Leiden, 1997, 115-52.

- Liebeschuetz W., “The Pagarch: City and Imperial Administration in Byzantine Egypt”, JJP 18, 1974, pp.163-168.

- Mazza R., “Ricerche sul pagarca nell'Egitto tardoantico e bizantino”, Aegyptus 75, 1995, 169-242.

- Morimoto K., The Fiscal Administration of Egypt in the Early Islamic Period, Dohosha, 1981.

- Morimoto K., “The Dīwāns as Registers of the Arab Stipendiaries in Early Islamic Egypt”, in R. Curiel and R. Gyselen eds., Itinéraires d’Orient hommages à Claude Cahen, Res Orientalis 6, 1994, 353-66.

- Mouton J. M., “L’Islamisation de l’Égypte au moyen âge,” in B. Heyberger ed., Chrétiens du monde arabe, Paris, 2003, 110-23.

- Mukhtar ‘A., “On the survival of the Byzantine administration in Egypt during the first century of the Arab rule”, Acta orientalia academiae scientiarum Hungaricae, Tomus XXVII 3, 1973, 309-319.

- Schaten S., “Reiseformalitäten im frühislamischen Ägypten”, Bulletin de la Société d’Archéologie Copte 37, 1998, 91-100.

- Sijpesteijn P., “New rule over old structures: Egypt after the Muslim conquest”, in H. Crawford ed., Regime change in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, London, 2007, 183-202.

- Sijpesteijn, P., “The Arab conquest of Egypt and the beginning of Muslim rule”, in R. S. Bagnall ed., Egypt and the Byzantine world 300-700, Cambridge, 2007, 437-457.

1.3. Documentary sources

- Abbott N., The Kurrah papyri from Aphrodito in the oriental institute, Chicago, 1938.

- Abbott N., "A new papyrus and a review of the administration of ‘Ubayd Allāh b. al-Ḥabḥab", in G. Makdisi ed., Arabic and Islamic Studies in Honor of Hamilton A.R. Gibb, Leiden, 1965, 21-35.

- Abū Ṣafiyya J., Bardiyyāt Qurra b. šarīk al-‘Absī, dirāsa wa taḥqīq, Riyad, 2004.

- al-Qāḍī W., “Early Islamic State Letters. The Question of Authenticity”, in A. Cameron and L.I. Conrad eds., The Byzantine and Early Islamic Near East. 1 Problems in the Literary Source Material, Princeton, 1999, 81-106.

- al-Qāḍī W., “An Umayyad papyrus in al-Kindi’s kitāb al-quḍāt”, Der Islam 84, (2008), 200-245.

- Balog P., Umayyad ‘Abbāsīd and Tūlūnīd glass weights and vessel stamps, New York, 1976.

- Bell H.I., “Two Official Letters of the Arab Period”, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 12, (1926), 265-81.

- Bell H.I., “Two Official Letters of the Arab period”, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 12, (1926), 265–81.

- Bell H.I., “The Arabic Bilingual Entagion”, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 89, (1945), 531–42.

- Diem W., "Der Gouverneur an den Pagarchen. Ein verkannter arabischer Papyrus vom Jahre 65 der Higra”, Der Islam 60, (1983), 104-111.

- Diem W., “Einige frühe Amtliche Urkunden aus der Sammlung Papyrus Erzherzog Rianer”, Le Muséon 97, (1984), 109–58.

- Eldada L., “Glass Weights and Vessel Stamps”, in J. Bacharach ed., Fustat Finds, Cairo, 2002, 112–66.

- Fahmy A., Ṣanğ al-sikka fī fağr al-Islam, Cairo, 1957.

- Grohmann A., “The value of Arabic papyri for the study of the history of medieval Egypt”, Proceedings of the Egyptian Society of Historical Studies 1, (1951), 41-56.

- Grohmann A., From the world of Arabic papyri, Cairo, 1952.

- Grohmann A., Studien zur historischen Geographie und Verwaltung des frühmittelalterlichen Ägypten. Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-historische Klasse Denkschriften, 77, Vienna, 1959.

- Hinds M. and Sakkout H., “A letter from the governor of Egypt to the king of Nubia and Muqurra concerning Egyptian-Nubian relations in 141/758”, Studia Arabica et Islamica, Beirut, 1981, 209-229.

- Hoyland R., “New documentary texts and early Islamic state”, Bulletin of the school of African and oriental studies 9, (2006), 395-416.

- George Miles, “Early Islamic weights and measures in Muntaza palace, Alexandria” JARCE, 3 (1964), 105-113.

- Morton A. H., A catalogue of early Islamic glass stamps in the British museum, London, 1986.

- Rabie H., The Financial System of Egypt A.H. 564-741/A.D. 1169-1341, Oxford, 1972.

- Raghib Y., “Lettres arabes (I)”, Annales Islamologiques 14, (1978), 15-35.

- Raghib Y., “Lettres nouvelles de Qurra b. šarīk”, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 40, (1981), 173-87.

- Sijpesteijn P., Shaping a Muslim state: papyri related to an eighth-century Egyptian official, In press, Oxford university press.

- Sijpesteijn P.M., “Multilingual Archives and Documents in Post-Conquest Egypt”, in Papaconstantinou A. ed., Multilingualism in Egypt, 2010, 105-124.

- Papaconstantinou A., “administrating the early Islamic Empire: Insights from the papyri”, in Haldon J. Money, powers and politics in early Islamic Syria.

- Bell H. I., Greek Papyri in British Museum IV, London, 1910.

- Gascou J., “De Byzance à l’Islam: Les impôts en Egypte après la conquête, à propos de K. Morimoto, The fiscal administration of Egypt in the Early Islamic Period”, JESHO 26, Leyden, (1983), 97-109.

- Mukhtar ‘A., “On the survival of the Byzantine administration in Egypt during the first century of the Arab rule”, Acta Orientalis 27, (1973), 309-19.

2. Barīd (Postal system)

2.1. Some medieval but important literary sources

-

al-Anṣarī, Tafrīğ al-kurūb fī tadbīr al-ḥurūb, ed./tr. G.T. Scanlon, Cairo 1961.

- al-Jahšiyārī (d. 331/942), Kitāb al-wuzarā’ wa-l-kuttāb, eds. M. al-Saqqā et al, Cairo 1937-8.

- al-Mas'ūdī (d. 345/956), Murūğ al-ḏahab wa ma‘ādin al-ğawhr, Beirut 1965.

- al-Qalqašāndī (d. 821/1418), Subḥ al-a‘šā fī ṣanā‘at al-inšā, Cairo 1913-22.

- al-Ṣūlī (d. 335/947), Adab al-kuttāb, eds. M. B. al-Aṭarī and 'A. M. al-Alūsī Sukrī, Cairo 1341/1923.

- al-Ṭabarī (d. 311/923), Ta’rīḫ al-rusul wa-l-mulūk, eds. M. J. de Goeje et al, Leiden 1879–1901.

- al-'Umarī (d. 749/1349), al-Ta'rīf bi-l-muṣṭalaḥ al-šarīf, Cairo 1894.

- Ibn al-Ṭiqṭaqā, Fakhrī fī al-ādāb al-ṣulṭāniyya wa al-duwal al-islāmiyya, Paris 1895.

2.2. Secondary sources

- Sprenger A., Die Post- und Reiserouten des Orients, Leipzig, 1864.

- Bligh-Abramski I., “Evolution versus Revolution: Umayyad Elements in the 'Abbasid Regime 133/750–320/932”, Der Islam 65, (1988), 226–43.

- Bravmann M., “The state archives in the early Islamic era”, Arabica 15, (1969), 87-89.

- Carrié J.-M., “Cursus Publicus,” in G. Bowersock, O. Grabar, and P. Brown eds., Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Post-Classical World, Princeton, 1999.

- Darādkeh Ṣ., “al-Barīd wa ṭuruq al-muwāṣalāt fī bilād al-šām fī al-‘aṣr al-‘abbāsī”, proceedings of the fifth international conference- Arabic section, Amman, 1991, 191-207.

- Dvornik F., The origins of intelligence services, New jersey, 1974.

- Elad A., “Aspects of the Transition from the Umayyad to the Abbasid Caliphate”, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 19, (1995), 89–132.

- Goitein S. D., “The commercial mail service in medieval Islam”, Journal of the American oriental society 84, (1964), 118-123.

- Heck P.L., The construction of knowledge in Islamic civilization: Qudāma b. Ja‘far and his kitāb al-ḫarāğ wa ṣinā‘at al-kitāba, Leiden, 2002.

- Sa'dawī N., Niẓam al-barīd fī ’l-dawla al-islāmiyya, Cairo, 1953.

- Silverstein A., “A new source on the early history of the Barīd”, al-Abḥāth 50-1, (2002-3), 121-134.

- Silverstein A., “On some aspects of the Abbasid Barīd”, in J. E. Montgomery ed., Abbasid studies: occasional papers of the school of the Abbasid studies, Leuven, 2004, 23-32.

- Silverstein A., Postal system in the pre-modern Islamic world, Cambridge, 2007.

- Silverstein A., “Etymologies and Origins: A Note of Caution”, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 28/1, (2001), 92–4.

- Sourdel D., “Barīd,” EI2, I, 1045.

2.3. Documentary sources

- Raghib Y., "Lettres de service au maître de poste d'Ashmun", Archéologie Islamique 3, (1992), 5-16.

- Silverstein A., “Documentary evidence for the history of the Barīd”, In P. M. Sijpesteijn and L. Sundelin eds., Arabic Papyrology and the History of Early Islamic Egypt, Leiden, 2004, 153–62.

3. Protocols

- Delattre A., “la réutilization des protocols aux époques byzantine et arab”, in Frösén J. et al. eds., Proceedings of the 24th international congress of papyrology, Helsinki, 2007, 215-220.

- Grohmann A., CPR III =[Corpus Papyrorum Raineri, Pt. 1, Allgemeine Einführung in die arabischen Papyri; Pt. 2, Protokolle], Vienna, 1924.

- Grohmann A., Arabic Papyri in the Egyptian Library I, Cairo, 1934.

- Grohmann A., From the world of Arabic papyri, Cairo, 1952.

- Grohmann A., Einführung und Chrestomathie zur arabischen Papyruskunde. I: Einführung, Prag, 1954.

4. Safe conducts/work permits

- Frantz-Murphy G., CPR XXI =[Arabic Agricultural Leases and Tax Receipts from Egypt, 148-427 A.H./ 765-1035 A.D.], Vienna, 2001.

- Frantz-Murphy G., “Identity and security in the Mediterranean world ca. AD 640 – ca. 1517,” in G. Traianos ed., proceedings of the 25th international congress of Papyrology, Ann Arbor, 2010, 253-264.

- Raghib Y., "Sauf-conduits d'Égypte Omeyyade et Abbasside,” Annales Islamologiques31, (1997), 143-168.

- Schaten S., “Reiseformalitäten im frühislamischen Ägypten”, BSAC 37 (1998), 91-100

- Wansbrough J. E., “The Safe-Conduct in Muslim Chancery Practice”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 34, (1971), 20-35.

1. Agriculture

- Banaji, J., “Late Antique Legacies and Muslim Economic Expansion”, in Haldon J. ed., Money, power and politics in early Islamic Syria: a review of current debates, Farnham-Burlington, 2010, 165-180.

- Bonneau D., Le régime administrative de l’eau du Nil dans l’Egypte grecque, romaine et byzantine, Leiden, 1993.

- Fairchild Ruggles, D., “The countryside: The Roman Agricultural and Hydraulic legacy of the Islamic Mediterranean”, in Jayyushi S., Holod R., Petruccioli A., Raymond A. ed., The City in Islamic World, Leiden, 2008, 795-816.

- Morelli F., “Nuovi' documenti per la storia dell'irrigazione nell'Egitto bizantino. SB XVI 12377, P.Bad. IV 93, SPP X 295-299, e altri”, ZPE 126 (1999) 195-201. (download here)

- Müller-Wodarg D., “Die Landwirtschaft Ägyptens in der frühen Abbāsidenzeit 750-969 n. Chr. (132-358 d. H.)”, Der Islam 31 (1954), 174-227; 32 (1957), 14-78; 141-67; 33 (1958), 310-21.

- Wilfong T.G., “Agricultural among the Christian Population of Early Islamic Egypt: Practice and Theory”, in Bowman A.K., Rogan E. eds., Agriculture in Egypt from Pharaonic to Modern Times, Proceedings of the British Academy 96, Oxford, 1999, 217–35.

2. Landholding

-

Al-Qāḍī W., “The Names of Estates in State Registers before and after the Arabization of the Dīwāns”, in Borrut A., Cobb P., Umayyad legacies, Medieval memories from Syria to Spain, Leiden, 2010, 255-280.

- Bagnall R. S., “Landholding in Late Roman Egypt: the distribution of wealth”, Journal of Roman Studies 82 (1992), 128-49.

- Duri A.A., “The Origins of ‘Iqta’ in Islam”, Al-Abhath 22 (1969), 3-22.

- Frantz-Murphy G., “Land Tenure and Social Transformation in Early Islamic Egypt”, in Khalidi T. ed., Land Tenure and Social Transformation in the Middle East, Beirut, 1984.

- Frantz-Murphy G., “Land-Tenure in Egypt in the First Five Centuries of Islamic Rule (Seventh-Twelfth Centuries AD)”, in Bowman A.K., Rogan E. eds, Agriculture in Egypt from Pharaonic to Modern Times, Proceedings of the British Academy 96, Oxford, 1999, 237–66.

- Gascou J., “Les grands domaines, la cité et l’état en Égypte byzantine (Recherches d’histoire agraire, fiscale et administrative)”, Travaux et Mémoires 9 (1985), 1-90.

- Hardy E.R., The large estates of Byzantine Egypt, New York, 1931.

Hickey T.M., “Aristocratic landowning and the economy of Byzantine Egypt”, in Bagnall R.E. ed., Egypt in the Byzantine World 450-700, Cambridge, 2007, 288-308. - Kennedy H., “Elite income in the Early Islamic State”, in Haldon J., Conrad L.I. eds., The Byzantine and Early Islamic Near-East: Elites old and new, LAEI VI, Princeton, 2004, 13-28.

- Lecker M., “The Estates of 'Amr b. al-‘Āṣ in Palestine”, BSOAS 52/1 (1989), 24-37.

Legendre M., “Caliphal estates and state policy over landholding: Late antique patterns and innovations in pre-iqṭā‘ Egypt”, in Authority and control in the countryside, Proceeding of the first conference on Late Antiquity and Early Islam: Continuity and Change in the Mediterranean 6th-10th century, Leiden, forthcoming. - Lev Y., State and society in Fatimid Egypt, Leiden, 1991.

- Lo Cascio E. ed., Terre, proprietari e contadini dell'impero romano, Dall’affitto agrario al colonato tardoantico, Rome, 1997.

- Morimoto K., “Land tenure in Egypt during the Early Islamic period”, Orient 11 (1975), 109-153.

- Morony M.G., “Landholding in Seventh-Century Iraq: Late Sassanian and Early Islamic patterns”, in Udovitch A.L. ed., The Islamic Middle-East 700-1900, Princeton, 1981.

- Richter T.S., “Cultivation of Monastic Estates in Late Antique and Early Islamic Egypt: Some Evidence from Coptic Land Leases and Related Documents”, in Boud’hors A., Clackson J., Louis C. and Sijpesteijn P. eds, Monastic Estates in Late Antique and Early Islamic Egypt: Ostraca, Papyri, and Essays in Memory of Sarah Clackson, Cincinnati, 205–215.

- Sato T., State and rural society in Medieval Islam, Leiden, 1997.

- Sijpesteijn P.M., “Landholding Patterns in Early Islamic Egypt”, Journal of Agrarian Change 9/1 (2009), 120– 133.

3. Administrative practices related to agriculture and landholding

- Al-Qādi W., “Population Census and Land Surveys under the Umayyads (41–132/661–750)”, Der Islam 83 (2006), 341-416.

- Banaji J., Agrarian Change in Late Antiquity: Gold, Labour, and Aristocratic Dominance, Oxford, 2001.

Cooper R.S., Ibn Mammātī’s Rules for the Ministries. Translation with Commentary of the Qawānīn al-Dawāwīn, PhD Dissertation, University of California Berkeley, 1966. - Cooper R.S., “Land Classification Terminology and the Assessment of the Kharāj Tax in Medieval Egypt”, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 17 (1974), 91-102.

- Frantz-Murphy G., The Agrarian Administration of Egypt from the Arabs to the Ottomans, Supplement aux. Annales Islamologiques 9, Cairo, 1986.

- Frantz-Murphy G., Arabic agricultural leases and tax receipts from Egypt, 148-427 A.H./765-1035 A.D., CPR XXI, Vienne, 2001.

- Morelli F., “Agri deserti (mawāt), fuggitivi, fisco, una κλήρωσις in più in SPP VIII 1183”, ZPE 129 (2000), 167-78. (download here)

- Noth A., “Some remarks on the ‘nationalisation' of conquered lands at the time of the Umayyads”, in Khalidi T. ed., Land Tenure and Social Transformation in the Middle East, Beirut, 1984, 223-228.

Poliak A.N., “Classification of Lands in the Islamic Law and its Technical Terms,’ The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures 57 (1940), 50-62. - Wipszycka E., Les ressources et les activités économiques des églises en Egypte du IVe au VIIIe siècle, Bruxelles, 1972.

- Wickham C., Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean 400–800, Oxford, 2005, 259-302.

4. Related medieval sources

- Abū Yūsuf (d. 182/798), Kitāb al-kharāj, ed. M.I. al-Bannā, Cairo 1981 tr. Ben Shemesh, Leiden, 1969.

- Ibn ‘Ādam al-Qurašī (m. 203/818), Kitāb al-ḫarāğ, ed. H. Mu’nis, Cairo, 1987.

- Abū ‘Ubayd b. Sallām (d. 224/838), Kitāb al-amwāl, ed. M.Kh. Harrās, Cairo, 1389/1969.

- Ibn ‘Abd al-Ḥakam (d. 257/871), Futūḥ Miṣr, ed. Ch. Torrey, The History of the Conquests of Egypt, North Africa and Spain, New Haven, 1922.

- Al-Balādurī, (d. 279/892), Futūḥ al-buldān, ed. M.J. de Goeje, Leiden 1866 (repr. 1992).

- Al-Ṭabarī (d. 310/923), Tārīḫ al-rusul wa al-mulūk, ed. M.J. de Goeje et al., Leiden 1964-5.

- Ibn Yūnus (d. 347/958), Tārīḫ Ibn Yūnus al-Miṣrī, éd. ‘A. ‘Abd al-Fattāḥ, Beyrouth, 2000.

- Al-Kindī (d. 350/969), Kitāb al-wulāt wa kitāb al-quḍāt, ed. R. Guest, The Governors and Judges of Egypt, Leiden 1912.

- Māwardī (d. 450/1058), Kitāb al-Aḥkām al-sulṭāniyya, ed. M. Enger, Bonn 1853/1909.

- Ibn Mammātī (d. 606/1209), Kitāb qawānīn al-dawāwīn, ed. A.S. Atiya, Cairo 1943.

- Ibn Duqmāq (d. 809/1406), al-Intiṣār li wāsiṭat ‘iqd al-amṣār, Cairo, 1893.

- Al-Qalqašandī, (d. 821/1418), Subḥ al-a‘šā fî ṣinā‘at al-inša’, Cairo, 1914-1922.

- Al-Maqrīzī (d. 845/1442), al-Mawā‘iẓ wa al-‘i‘tibār fī dikr al-ḫiṭaṭ wa al-Ātār, ed. A.F. Sayyid, London, 2002-2004.

- Ibn al-Ǧiʿān (d. 884/1480), Tuḥfat al-sanīya bi asmā’ al-bilād al-maṣrīya, ed. B. Moritz, Cairo, 1898.

1. Overviews of the entire fiscal system

- Bæk Simonsen J., Studies in the genesis and early development of the caliphal taxation system: with special references to circumstances in the Arab Peninsula, Egypt and Palestine, Kopenhagen, 1988

- Bell H.I., Greek papyri in the British Museum: catalogue with texts, IV: The Aphrodito papyri, Oxford, 1910 [P.Lond. IV]

- Dennett D.C., Conversion and the poll tax in early Islam, Cambridge, Ma., 1950

- Hussein F., Das Steuersystem in Ägypten von der arabischen Eroberung bis zur Machtergreifung der Ṭūlūniden 19-254/639-868 mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Papyrusurkunden, Heidelberger orientalistische Studien 3, Frankfurt am Main, 1982

- Morimoto K., The fiscal administration of Egypt in the early Islamic period, Asian historical monographs 1, Kyoto, 1981 [+ Gascou J., “De Byzance à l’Islam: les impôts en Egypte après la conquête arabe”, JESHO 26/1 (1983), 97-109]

2. Studies

- Abbott N., “A new papyrus and a review of the adminstration of ‛Ubaid Allāh b. al-Ḥabḥāb”, in Makdisi, G. (ed.), Arabic and Islamic studies in honor of Hamilton A.R. Gibb, Leiden, 1965, 21-35

- Abū Ṣafiyya Ǧ. b. Ḫ., Bardiyyāt Qurra b. Šarīk al-‛Absī, Riadh, 2004

- Becker C.H., Beiträge zur Geschichte Ägyptens unter dem Islam, 2 vols., Strassburg, 1902-1903

- —, “Die Entstehung von ‛Ušr und Ḥarāǵ-Land in Ägypten”, Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 18 (1905), 301-19

- —, Islamstudien: v om Werden und Wesen der islamischen Welt, 2 vols., Leipzig, 1924 & 1932

- Bell H.I., “The Aphrodito papyri”, The journal of Hellenic studies 28 (1908), 97-120

- —, “The administration of Egypt under the ‛Umayyad Khalifs”, Byzantinische Zeitschrift 28 (1928), 278-286

- —, “The Arabic bilingual entagion”, Proceedings of the American philosophical society 89/3 (1945), 531-45

- Ben Shemesh A., Taxation in Islam, 3 vols., Leiden, 1965-1969

- Biedenkopf-Ziehner A., “Christen und Muslime im Spiegel Thebanischer Urkunden des 7.-9. Jh.”, in Beltz W. (ed.), Die koptische Kirche in den ersten drei islamischen Jahrhunderten: Beiträge zum gleichnamigen Leucorea-Kolloquium 2002, Halle, 2003, 41-70

- Carrié J.-M., “L’État à la recherche de nouveax modes de financement des armées (Rome et Byzance, IVe-VIIIe siècles)”, in Cameron A. (ed.), The Byzantine and the early Islamic Near East 3: States, resources and armies, Princeton, N.J., 1995, 27-60

- Casson L., “Tax collection problems in early Arab Egypt”, Transactions and proceedings of the American Philological Association 69 (1938), 274-291

- Chalmeta P., “Consideraciones sobre establecimiento de la fiscalidad musulmana (644-750)”, in Curiel R., Gyselen R. (eds.), Itinéraires d'Orient: hommages à Claude Cahen, Bures-sur-Yvette, 1994, 103-110

- —, “Fiscalité musulmane: au sujet du ṭabl”, in Halff B., et al., L’Orient au coeur: en l’honneur d’André Miguel, Paris, 2001, 217-222

- Cooper R.S., “The assessment and collection of Kharâj in medieval Egypt”, JAOS 96 (1974), 365-382

- Donner F.M., “The formation of the Islamic state”, JAOS 106/2 (1986), 283-296

- Fattal A., Le statut légal des non-Musulmans en pays d’Islam, Recherches 10, Beirut, 1958

- Fahmy A.M., Muslim sea power in the eastern Mediterranean from the seventh to the tenth century A.D., Cairo, 19662

- Foss C., “Egypt under Mu‛āwiya part II: Middle Egypt, Fusṭāṭ and Alexandria”, BSOAS 72/2 (2009), 259-78

- Frantz-Murphy G., “A comparison of the Arabic and earlier Egyptian contract formularies”, JNES, I: 40 (1981), 203-225, 355-356; II: 44 (1985), 99-114; III: 47 (1988), 105-112; IV, idem., 269-280

- — , “Agricultural tax assessment and liability in early Islamic Egypt”, Atti del XVII congresso internazionale di papirologia, Napels, 1984, III, 1405-1414

- —, “Land tenure and social transformation in early Islamic Egypt”, in Khalidi T., Land tenure and social transformation in the Middle East, Beirut, 1984, 131-139

- —, The agrarian administration of Egypt from the Arabs to the Ottomans, Cairo, 1986

- —, “Conversion in early Islamic Egypt: the economic factor”, in Rāġib Y. (ed.), Documents de l’Islam médiéval: nouvelles perspectives de recherche, Cairo, 1991, 11-17

- —, “Settlement of property disputes in provincial Egypt: the reinstitution of courts in the early Islamic period”, Al-Masāq 6 (1993), 95-105

- —, “Land-tenure in the first five centuries of Islamic rule”, in Bowman A.K., Rogan E. (eds.), Agriculture in Egypt from pharaonic to modern times, Oxford, 1999, 237-266

- —, “The economics of State formation in early Islamic Egypt”, in Sijpesteijn P.M., et al. (eds.), From al-Andalus to Khurasan: documents from the medieval Muslim world, Leiden, 2007, 101-14