Website

Clinton won, but the horserace continues

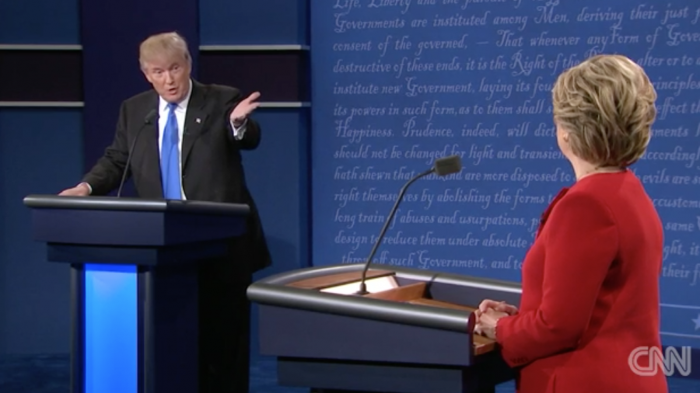

Let’s get this out of the way: Hillary Clinton won the 26 September 2016 presidential candidates television debate. Handily.

- Author

- Rebekah Tromble

- Date

- 28 September 2016

Despite starting out relatively well, about 15 minutes into the debate, Trump became so flustered by Clinton’s subtle but constant goading that he began making one gaffe after the next—effectively admitting that he does not pay federal income tax, claiming ISIS has been around for 30 years, talking about Rosie O’Donnell, and so on. By the end, his sentences barely made sense. Clinton, in contrast, remained cool, calm, and collected in the face of Trump’s attacks, and she deftly pivoted away from her own controversies (especially emails) back to policy issues.

That said, I found the follow-up commentary and analysis even more interesting than the debate itself. I monitored a number of American outlets—CNN, NBC, CBS, and 538—both on television and online, as their pundits dissected the debate in its immediate aftermath. And a common theme emerged: Despite early consensus that Clinton had easily prevailed, commentators quickly began minimizing her victory: She won, but does it really matter? Would it effect the polls? 538’s Nate Silver—who is usually one of the most responsible and measured commentators in the business—even equivocated, saying, “This was a pretty bad performance [for Trump], and the initial after-debate polls say Trump lost pretty badly. If this can’t help Clinton out, then she’s got problems.”

That’s right. Clinton trounced Trump. But she’s still got problems.

This is a classic media move. After a week of pumping up this debate as the most consequential event in the campaign, suddenly commentators are wondering if it really was that important after all. The debate was significant when it could generate a media audience. But now that it is over, the horserace must continue one way or another. And it must remain close. Otherwise, why would people pay attention?

Indeed, I see just how effective the horserace narrative is in my classroom these days. I am currently teaching a course on media and politics to about 75 bachelor students. I have taught this class for six years now, but I have never had a group so engaged. They want to talk about the American election all the time, and they use the campaign as a lens for understanding just about every concept and idea I introduce.

As their teacher, I should love this. But I don’t.

The problem is that covering elections—and politics more broadly—as a never-ending horserace generates public cynicism. As political scientists Joseph Cappella and Kathleen Jamieson have shown, when politics is boiled down to winning and losing, people presume that politicians are merely self-interested. They do not care about solving problems and improving society. They only care about securing the win, defeating their opponents. Politics, it seems, is nothing more than a game.

And thus, while my students may be more engaged in class than ever, they are also jaded and pessimistic. They consider the American political system profoundly broken, but they don’t see the Dutch (or any other) system as much better. Indeed, it all seems so damaged, many doubt if political dynamics can ever be fixed. They openly wonder if there is any point in trying to participate in democratic processes.

And so, though I am happy and relieved that Clinton performed well, and I know that the debate has stimulated further excitement in my classroom, I also realize that the media’s reflexive, instantaneous return to the horserace narrative will make it that much harder to inspire political participation and engagement.