Dissertation

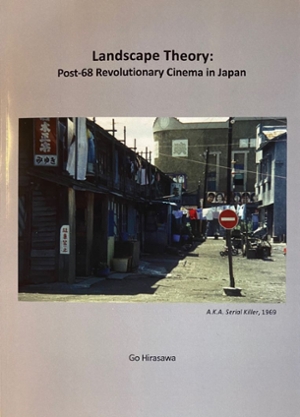

Landscape Theory: Post-68 Revolutionary Cinema in Japan

On the 28th of September Go Hirasawa successfully defended a doctoral thesis and graduated.

- Author

- Go Hirasawa

- Date

- 28 September 2021

Summary

This dissertation reexamines and considers landscape theory, which was proposed by film critic and anarchist Matsuda Masao in 1969, and further developed by film director Adachi Masao, screenwriter Sasaki Mamoru, and photographer Nakahira Takuma as a new theory of politics and revolution that moved beyond the framework of film history and art theory. The birth of landscape theory coincided with the production of the film Ryakusho Renzokushasatsuma (A.K.A. Serial Killer,1969),a documentary film about an absent protagonist, nineteen-year-old Nagayama Norio, who had been convicted of a series of indiscriminate gun murders that had occurred between October 1968 and April 1969, in Tokyo, Kyoto, Hakodate and Nagoya. The film consists entirely of shots of landscapes that he may have encountered in his wandering from his birth until his arrest. The incident had an enormous social impact in postwar Japan, particularly because Nagayama was one of the so-called ‘golden eggs’ (kin no tamago), the young workers who came from rural areas to Tokyo to work as unskilled labor in support of the booming economy.

It was not until the introduction of the term 'fukei' as the translation of the English word 'landscape' during the modernization process of the Meiji Restoration, in the latter half of the 19th century, that the term and concept 'fukei' (landscape) started to be used in Japan. Prior to that, various terms such as 'kokei' (scene) and 'keshiki' (view) were used interchangeably with 'landscape,' however when the western notion of 'landscape' took root, discussions about landscape started to develop in various fields. This dissertation, therefore, first introduces a historical overview of various theories of landscape in Japan, and through comparisons with them, argues for the specificities of the landscape theory that Matsuda, Adachi, and others had developed in an entirely different context from those of its predecessors.

A new post-war regime had been established in Japan under the American occupation, without accountability for the war having been thoroughly examined. Problems such as this were brought to light through the Japan-US Security Struggle in1960, and as a result the New Left movement was born. Further in 1968-69, Zenkyoto (the All-Campus Joint Committee) movement, organized mainly by students, gained momentum almost to the point of dismantling the existing system of state capitalism. The 1960s thus became a major transitional period after the war. However, starting around 1970, the movement’s momentum was suppressed by an overwhelming police and military force, and this marked the arrival of high consumer society. It was in the midst of these historical shifts that landscape theory was initially conceived, as a theory of film and photography, aiming for a new 'post-1968' thought and practice, rather than succeeding previous artistic and revolutionary theories. Landscape theory attempted to locate the power-state not in a typical political domain, but rather in the ordinary everyday landscape, expanding the interpretation of existing discussions dealing exclusively with visible landscape further, to the extent of naming invisible as well as visually recognizable structures 'landscape. Despite its great potential as a new theory of power-state, and as a revolutionary theory for the 1970s, landscape theory experienced difficulties, and was forced to change its theoretical direction. This shift was due to the fact that numerous controversies arose, caused by factious criticisms regardless of their sources, such as film, photography and politics, as well as the fact that discussions of landscape theory had become a sort of cultural trend, result of which was the return of so-called 'Historical' theories of landscape. Another cause of this shift was a series of events in the lives of the main theorists of landscape theory: Adachi left Japan in 1974 to join the Arab Red Army (later the Japanese Red Army) for the Palestinian Revolution; Matsuda planned to move his living base to Europe, but was deported from France; and Nakahira suffered a severe memory loss. Tracing this background and course of events, this dissertation elucidates the historical and theoretical position of the newly created landscape theory in Japan, and, with an eye on the early 2000’s reassessment of landscape theory, further explores its contemporary relevance and potential.

"Introduction" offers a reassessment of Adachi's life and work, as well as various currents of reinvestigation of landscape theory in Japan and abroad, which started upon his deportation from Lebanon to Japan in 2000. Chapter One, "Landscape and Landscape Theory," traces and examines how the concept of landscape had taken root in the process of Japan’s modernization, and how discussions around it subsequently unfolded. The discussions are diverse in content, starting from Nihon Fukeiron (On the Japanese Landscape) by geographer Shiga Shigetaka, published in 1894, to Chijinron (Discourse on the earth-human relation) by another geographer, Uchimura Kanzo, to a series of travel writings by folklorist Yanagita Kunio, to Fudo (Climate) by philosopher Watsuji Tetsuro, as well as to Musashino, by literary person Kunikida Doppo. There are additional discussions of landscape that have rarely been brought up in the context of theories of landscape, by people such as film directors Kamei Fumio, Mizoguchi Kenji, literary persons Dazai Osamu, Sakaguchi Ango, critics Yasuda Yojuro, and Hanada Kiyoteru. Encompassing geography, philosophy, ethnology, sociology, as well as theories of photography, film, literature, state, and culture, historical and theoretical changes of landscape and theories of landscape in Japan are traced. Through comparison with the above, the unique and innovative aspects of Matsuda’s landscape theory is brought to light.

In Chapter Two, " Matsuda Masao’s Landscape Theory," various texts by Matsuda, the central ideologue of landscape theory, are examined. Mainly based on his two essays, "Sex as landscape" and "City as Landscape," in which a theorization of landscape was initially attempted, the focus is to analyze landscape theory that had been developed in his discussions on films, including Oshima Nagisa's Tokyo senso sengo hiwa (The Man Who Left His Will On Film, 1970), culture, and politics. The possibilities of his texts as theories of state power, underclass proletariat, commune, guerrilla, and revolution are clarified through the exploration of key concepts, such as the collapse of dichotomies between Tokyo and the countryside, between center and periphery, the regimentation of the entire Japanese archipelago as a gigantic city, and the homogenization of the landscape, as well as the relations between the act of seeing/being seen and the subject. Also, by examining theoretical responses to Matsuda's landscape theory by Nakahira, Adachi, Sasaki and others, as well as the critical exchanges between Matsuda and filmmaker Hara Masato and critic Tsumura Takashi, the development that led to a polemical debate on landscape theory, and its process of decline is traced. Discussions of landscape—contemporaneous to Matsuda and others' landscape theory—by literary scholar Okuno Takeo, architects Miyauchi Ko, and Hara Hiroshi, as well as new theories of landscape written after Matsuda and others' landscape theory, by literary critic Karatani Kojin and others, are reviewed as well. Furthermore, the theory of reportage and information media, which is considered as a theoretical successor to landscape theory, along with the theory of cinema movement that was concurrently developed, is referenced.

Chapter Three, "On Adachi Masao" and "On Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War";focus on examining two films: A.K.A. Serial Killer, which led to the creation of landscape theory, and the newsreel film Sekigun- PFLP: Sekai senso sengen (Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War, 1971), produced by Wakamatsu production and jointly edited by the Red Army Faction of;Communist League (Kyosanshugisha Domei Sekigunha) and the PFLP (Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine). Red Army/PFLP, on which Adachi did the directing, shooting and editing, depicts the Palestinian liberation struggle, and the revolutionary struggle in Japan, as texts for world revolution.

First, while touching on the cultural and historical background of the New Wave cinema movement in Japan spanning from the late 1950's to the early 1960's that saw the debut of Adachi, A.K.A. Serial Killer is analyzed in order to discuss how its methodology of using only images of landscape rather than a narrative brought forth new aesthetic and political possibilities of the film as visual medium.

Furthermore, Adachi's remarks on landscape theory are gathered from interviews, conversations, roundtables and his own texts, and the theoretical development from landscape theory to theory of reportage and information media through the production of Red Army/PFLP is also examined. In addition, along with a film theoretical and political analysis of Red Army/PFLP, an analysis of the relationship between film theory, production, and screening in light of the screening troop movement for Red Army/PFLP is conducted.

In Chapter Four, "Wakamatsu Koji, Oshima Nagisa, Jean-Luc Godard and Dziga Vertov Group," the work of Wakamatsu Koji and Oshima Nagisa, both filmmakers who worked with Adachi and Matsuda, and whose work is particularly relevant to landscape theory, is examined. Focusing particularly on Wakamatsu's Yukeyuke nidome no shojo (Go Go, Second Time Virgin, 1969), Kyosojoshiko (Running in Madness, Dying in Love, 1968), Sex Jack (1970), as well as Oshima Nagisa's Shonen (Boy, 1969), and The Man Who Left His Will on Film, an analysis based on the statements of both filmmakers about these works and landscape, is conducted. Also, the Wakamatsu and Oshima films are compared with those of Jean-Luc Godard, as well as films from the Dziga Vertov Group period, particularly with Wind From the East (1969), Lotte in Italia (1969), and Here and Elsewhere (Ici et ailleurs, 1975) that were made under the theme of landscape and politics, to examine cinematic and political approaches to landscape—not only in the Japanese context, but also in global context of radical international filmmakers of the same period. In conclusion, by reflecting on these investigations and analysis, under the current situation in Japan, in which the return of so-called 'master narratives,' such as 'postwar reconstruction' and 'high economic growth' is becoming prominent, the challenge of formulating a new landscape theory in order to again resist such a move is discussed anew.

Supervisors: prof. dr. Ivo Smits and prof. dr. Nicole Brenez (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle Paris III)