A Dutch Robespierre? Dissertation sheds new light on Leiden revolutionary Pieter Vreede

PhD image: George Kocksen/ Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

Leiden patriot Pieter Vreede (1750-1837) fought for greater popular influence with blazing pamphlets and even a coup d’état. In his PhD dissertation, historian Dirk Alkemade reveals how this idealistic pioneer used radical means to shape Dutch democracy.

Coups d’état, political purges, armed citizen militias: at the end of the 18th century, a revolution swept through the Netherlands. During the patriottentijd (Patriot Era, 1780-1787) and the Batavian Republic (1795-1801), various factions vied for power. At stake: who governs the country and what does freedom mean in practice?

Pioneers of democracy

‘The patriots and Batavians laid the foundations for modern democratic Netherlands’, says Alkemade. ‘But for a long time, they failed to receive the recognition they deserved.’ That’s why he wrote his dissertation about these radical reformers, with a central role for Pieter Vreede. This Leiden pioneer demanded more power for the people and an end to aristocratic rule. He was also one of the few outspoken opponents of slavery at the time. Vreede penned radical pamphlets attacking the stadtholder and the elite. Alkemade research into these political writings revealed that in 1786, Vreede filled an entire journal titled Iets gewigtigs voor Leyden (Something of Importance for Leiden).

Second-class citizen

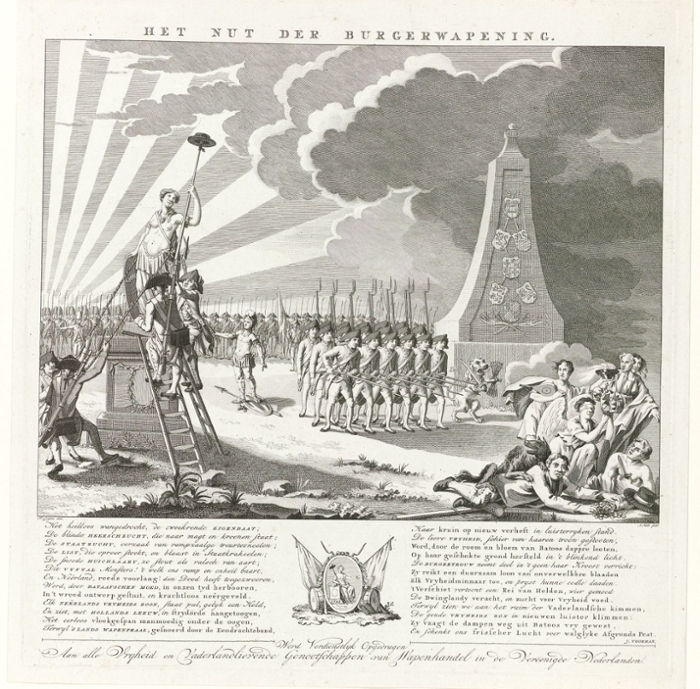

To understand Vreede’s political motives, Alkemade took a biographical approach to his life and works. Vreede came from a prominent Mennonite family of Leiden cloth manufacturers and studied law in Leiden. Around 1780 he was one of the first in the country to call for representative democracy. As a member of the Mennonite community, Vreede felt like ‘a second-class citizen’, says Alkemade, and this may explain his fanaticism. ‘Mennonites like Vreede had to constantly fight for their place in society.’ In addition to writing pamphlets, Vreede gave inflammatory speeches and founded vrijkorpsen -- armed citizen militias that sought to exert political influence and counter the military power of the stadtholder.

Coup d'état

In 1796, Vreede took a seat in the first national parliament of the Batavian Republic, but he quickly grew frustrated by the slow pace of reform. In January 1798, he and his allies therefore staged a coup. As new leader of the Executive Authority, Vreede expelled opponents from parliament and disenfranchised thousands of moderates. The radicals drafted a new constitution, which was adopted by referendum. ‘The adoption of the 1798 constitution marks a crucial step in the modernisation of Dutch politics’, says Alkemade.

The Dutch Robespierre

Vreede’s actions earned him the nickname ‘the Dutch Robespierre’, after the French revolutionary Maximilien de Robespierre, who enforced the French revolution through bloodshed. Vreede strongly rejected the comparison: unlike in France, there had been no mass arrests or executions in the Netherlands. But his rule came to an abrupt end in June 1798, when his political opponents launched a second coup. Vreede fled and withdrew from politics.

Words and weapons

Alkemade also challenges the notion that the Dutch revolutionaries merely copied the French revolutionaries. ‘By dismissing this period as “the French era” historians have long perpetuated the false idea that the Dutch revolution was somehow un-Dutch.’ With his dissertation, Alkemade aims to shed new light on the origins of Dutch democracy: ‘Many people think Dutch politics has always been relatively calm, but that is a real misconception. Dutch democracy was hard-fought, with words and weapons.’