Walking in a city of the dead

They call their team ‘The Walking Dead’: Leiden Egyptologists Lara Weiss, Huw Twiston Davies and Nico Staring. A fitting name for a group that conducts research into Saqqara, an Egyptian city of the dead. ‘We are trying to trace religious traditions. What did these mean for people’s lives and burying and remembering their dead?’ Their first findings can now be seen at the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, in the exhibition ‘Saqqara. Living in a City of the Dead.’

Close to Cairo lies Saqqara, an Egyptian city of the dead. The remains of the city can still be seen and excavations are still carried out there. It used to be full of tombs and temples, including the famous step Pyramid of Djoser, the earliest monumental stone building in the world. Saqqara was not any old burial ground: for thousands of years it was used at a place to bury not only kings but also regular mortals and as a place to worship the gods. ‘This long period of use is what makes it so interesting,’ says Staring. ‘Ancient Egyptians came there to build or visit their family tomb and for them too the Pyramid of Djoser was an ancient monument from the distant past.’ Temples have disappeared or tombs have been built over earlier structures. Staring compares this with the centre of Leiden. ‘That is a medieval town that is still in use. Some things have changed: buildings have disappeared or canals been filled in. But some things are the same as they were in 1500. The present-day streetscape is never fully modern: it’s a combination of old and new.’

Museum exhibits in their context

A few days before the opening, three researchers give us a tour of their exhibition, as the finishing touches are made. The objects come from Saqqara but they didn’t excavate them themselves. The National Museum of Antiquities has been conducting excavations in Saqqara since 1975, but acquired most of the exhibits a long time before this. ‘With our research, we want to provide more context for these objects and gain a better understanding of the Ancient Egyptian burial ground,’ project leader Weiss explains. Each researcher takes a slightly different perspective, and they illustrate this with their favourite objects in the exhibition.

A priest’s inheritance

In the research into Saqqara, Staring principally looks at the use of the area, space and structures. However, the object that he chooses is neither structure nor map but a papyrus roll with a text. It is the inheritance document of a specialised priest from Saqqara, from 256 BC. These priests were like wardens of the city of the dead: they redistributed tombs or sold ones that had fallen into disuse to new families. ‘As this priest records his inheritance, he gives a very precise summary of the tombs that he had in his service. This gives me an impression of what the area looked like and of temples, procession routes and graves that have since disappeared or that we may find somewhere under the sand. The priest describes what Saqqara looked like in 256 BC.’

Motif from the past

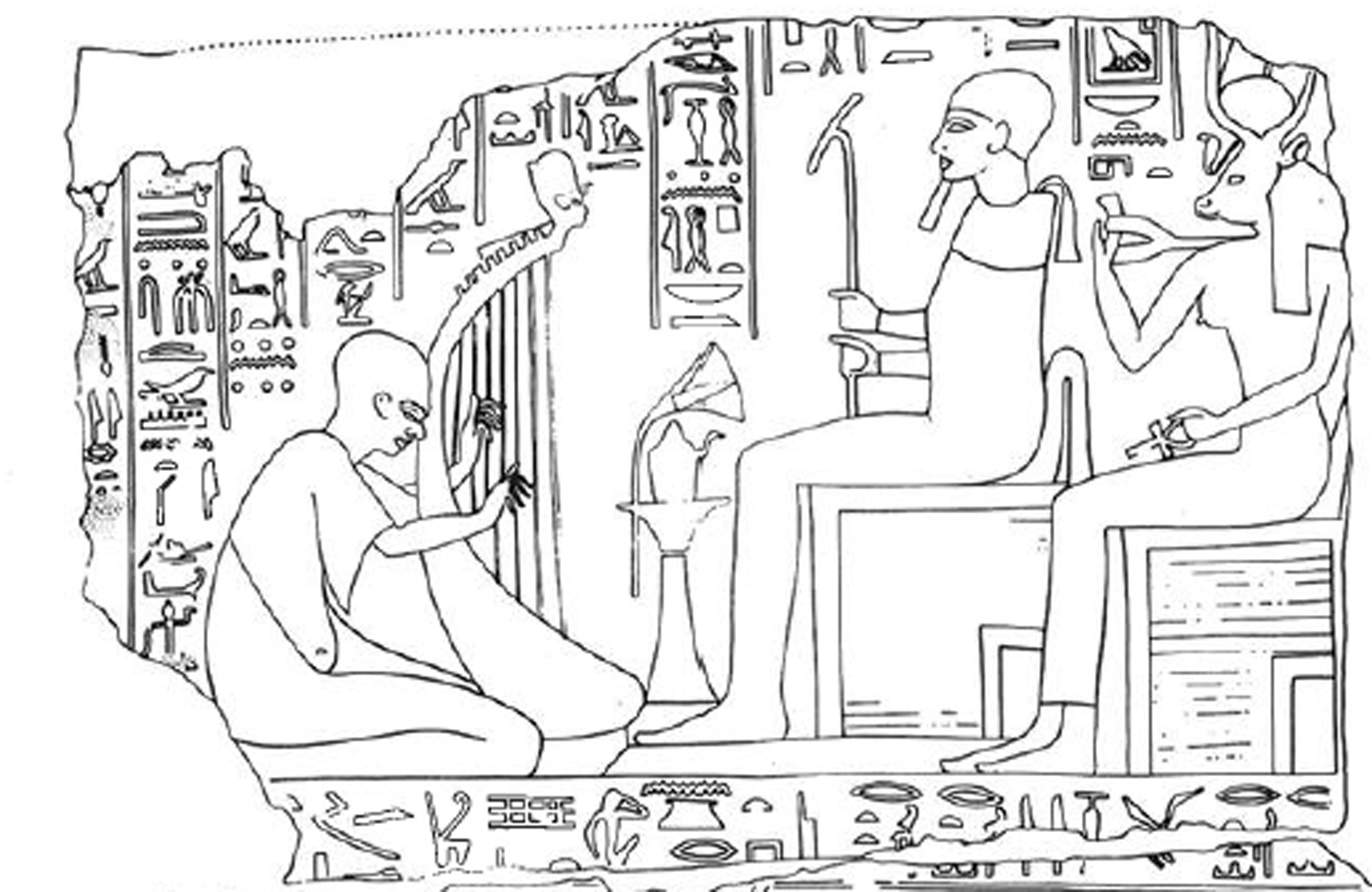

Twiston Davies is next and leads us to a stela – a tombstone or part of one. ‘This stela doesn’t come from Saqqara at all and is earlier than the period that we focus on. But it fits in with the exhibition because it illustrates well what I look at in our project.’ On the stela we can see a relief of the two deceased, seated on chairs, with a harp player at their feet, an image that was often used in tombs. Twiston Davies then points to the image alongside, also of a harp player at the feet of two seated figures. This one does come from a tomb in Saqqara. Twiston Davies: ‘It looks like exactly the same picture but here the harp player is the deceased himself, namely Raia, the chief singer at one of the temples. The figures on the throne are two gods.’ It is the same motif, but then in a somewhat different form. ‘I research these kinds of change in the texts and images on the graves at Saqqara: how motifs are taken and adjusted to taste. This tells us more about how people built on their own history at the time.’

-

The Stela of Iki (from Abydos, 1938-1760 BC). At the top a harpist plays for the deceased, the two seated figures. -

The image that was found in the tomb of Raia at Saqqara. The same motif is used again, but in a changed form: now it is the deceased Raia who is playing for the gods.

Burying the dead is a family affair

Weiss’ favourite piece in the exhibition is also a stela, the Stela of Meryptah. ‘This shows the everyday religious practices in a number of different ways,’ Weiss explains. On the stela, we can see five figures, two women and three men. ‘These are Meryptah, his parents and his brother. Their relationship to the fifth person we don’t know exactly. It is probably one of Meryptah’s fellow priests. The group of figures shows that such a tomb was a real family affair – but that the Egyptians also understood family in a very wide sense of the word.’ On the uppermost edge of the stela is a text addressing the living, Weiss explains. This asks the living to make offerings for the dead. ‘The dead hoped that the living would come and visit them at the burial ground to honour them.’

Research at a museum

While we walk around, the finishing touches are being made to the exhibition. The Walking Dead team looks with satisfaction at the images on the wall and the labels for the objects. They found it difficult to write the labels. Twiston Davies: ‘The labels can’t be too long, so you have to omit a lot. And you mustn’t make it too difficult by using jargon or expecting your audience to have too much prior knowledge, but it can’t be too simple either. The project leader of the exhibition, Leonie van Esser, was very helpful in that respect.’ All three think it is fantastic to be able to transform their academic work into an exhibition. Weiss: ‘As a university researcher you write a book or paper for maybe 100 of your peers. In an exhibition such as this we can tell hundreds of museum visitors about our research.’

Text: Marieke Epping

Photo above: The excavations in Saqqara, with the Pyramid of Djoser in the background

Other photos: National Museum of Antiquities, all rights reserved

Mail the editors

Saqqara. Living in a City of the Dead

The exhibition ‘Saqqara. Living in a City of the Dead’ can be seen at the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden from 10 March to 22 November. The exhibition is part of Weiss’ research project ‘The Walking Dead at Sakkara: The Making of a Cultural Geography’, for which she received a VIDI grant from the Dutch Research Council in 2017. The research team will return to Saqqara for further excavations while the exhibition is on. Follow their progress in weekly updates from 20 March to 16 April at www.rmo.nl/sakkara.

As of 1 June, the RMO is open to visitors again. Reservation is required: https://www.rmo.nl/online-reserveren/ The exhibition on Sakkara is prolonged until 22 November.