How Leiden became 'the wonder of Europe'

Curiosities from the anatomical theatre, swords from the fencing school and 17th-century portraits of the University's founders. The new University Room in Museum De Lakenhal portrays the turbulent first hundred years of Leiden University.

The first thing you see is an enormous 17th-century swordfish suspended from the ceiling; it is the oldest of its kind in the Netherlands. The fish was brought ashore in 1683, mounted by Leiden medical experts and exhibited in the academy's anatomical theatre. Visitors to the new University Room will feel as though they are in an enormous curiosity cabinet. In the glass display cases are swords that former students learnt to fence with. There are also antique measuring instruments on display, and if you open one of the drawers you will see iconic prints from 1610 of such University locations as the Hortus botanicus and the fencing school. American artist Mark Dion has given the phenomenon of the cabinet of curiosities a contemporary twist: he has created fluorescent replicas of mounted animals, curiosities and instruments specially for this room.

Influence of the city on the University

‘Leiden as a university city is one of the seven themes of the new museum,’ explains Jori Zijlmans, history curator at Museum De Lakenhal. After almost three years of renovations and extensions, the museum reopened in June this year. Zijlmans: ‘We wanted to show this interaction between the city and its residents: how did Leiden residents experience the presence of the University and what impact did the University have on the city?’

One example of this is a wooden statue of Lady Justice representing the academic court or tribunal. The University had its own court, but some of the aldermen in the tribunal were from the city council and the trials took place in the city hall.

Relief of Leiden

The room shows how closely the city and University were bound together in the turbulent years after the University’s foundation. There are 17th-century portraits of University governors on display, including adviser Cornelis van Hoogeveen and city commander Jan van der Does. Van der Does was a friend of William of Orange, who instructed him to found a university. Van der Does did this together with Jan van Hout, Leiden’s town clerk. These three men were members of the first Board of Governors of the University. They ensured that Leiden gained some important institutions – the Hortus botanicus, the University Library and the anatomical theatre.

Scaliger

In the early days of the University there was just a handful of academics and a few students. But thanks to the recruitment of famous scholars such as French humanist Joseph Scaliger and the new institutions such as the Hortus botanicus, Leiden attracted increasing numbers of international academics and students in the 17th century. From an industrial city made up mainly of workers, Leiden evolved over a period of a hundred years into an international intellectual hub. It was not without reason that a French encyclopaedia described the developing Leiden academy in 1650 as the ‘wonder of Europe.’

Spear and iPod

The University Room is next to the large room devoted to the Siege and Relief of Leiden in 1573 and 1574. The University was an outcome of the Relief of Leiden after all, says Zijlmans. Works are on display here also feature key players in the University’s history. The metre-high work by photographer Erwin Olaf, for instance, which depicts the Relief of Leiden and features the victorious duo Jan van der Does and Jan van Hout. Olaf also has introduced contemporary elements to this historic tableau: look carefully and you will see that one of the figures is holding an iPod.

Nobel Prize

In other rooms are artworks referring to the University in later periods, such as ‘The elements,’ a painting by Harm Kamerlingh Onnes. This painting, from 1920, is an impression of the laboratory of his uncle, the eminent physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, who was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1913 for his research on the properties of matter at low temperatures.

This autumn will see the start in Museum De Lakenhal of the Young Rembrandt – Rising star exhibition (2 November 2019 to 9 February 2020). Rembrandt enrolled as a student of the arts at Leiden University in 1620, and this year it was discovered that he was still enrolled in 1622. The original register with Rembrandt’s signature can be seen as part of the exhibition. This album studiosorum comes from the collection of the University Library.

Text: Linda van Putten

Mail the editors

-

The statue 'Rembrandt in artist's smock' by Gabriël Sterk is on temporary display until 9 February 2020. -

During the renovations, part of the roof was removed so that the facade is again visible. Photo: Museum De Lakenhal/Karin Borghouts -

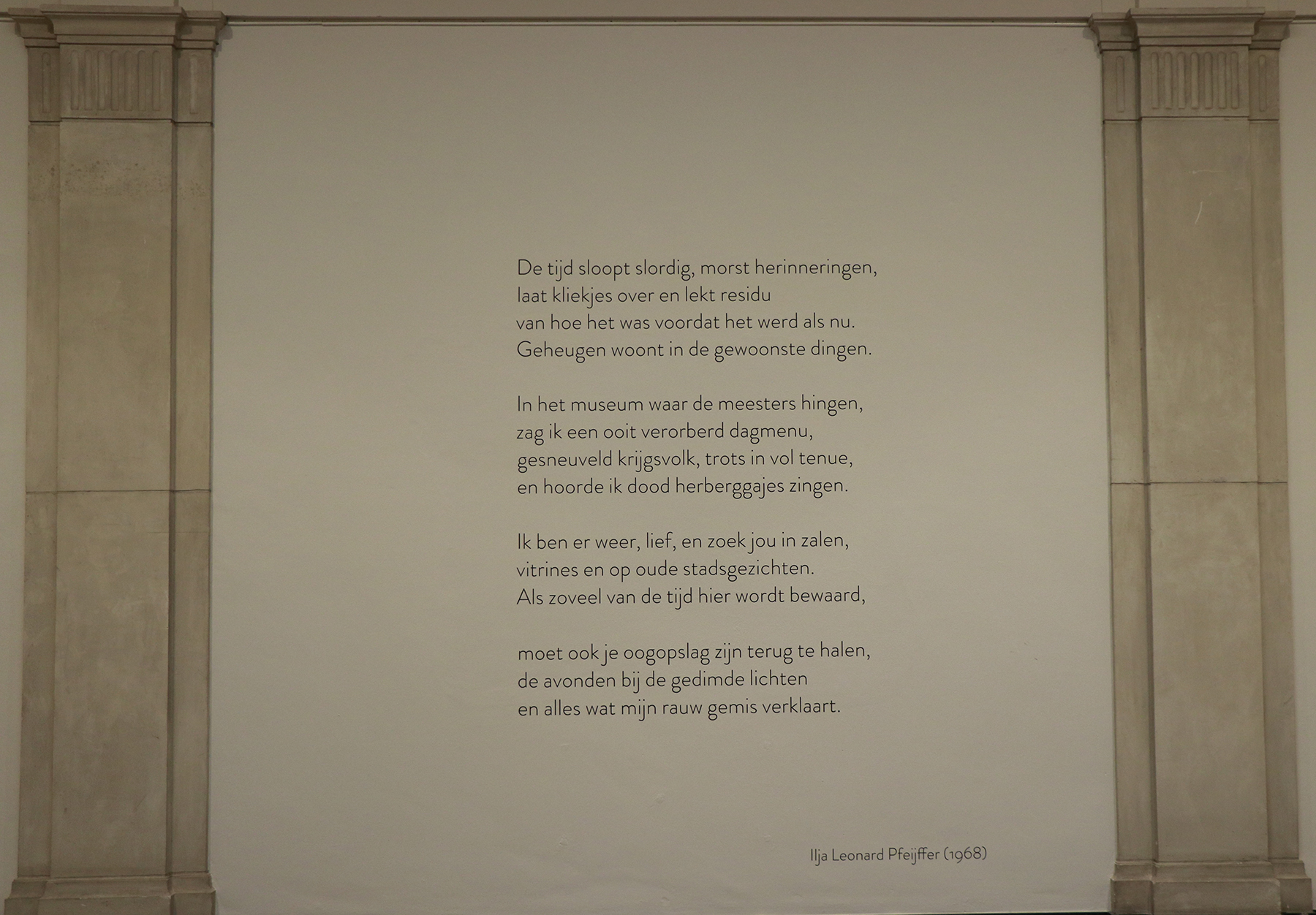

A prominent exhibit in the stairwell is a wall poem by poet and writer Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer. He studied classical languages in Leiden, was awarded a doctorate here and worked at the University for a period of time as a scholar of classics.