Utrecht: Unexpected allies and food activism in quarantine

This blogpost is a reflection of research assistant Marilena Poulopoulou on the food relief initiative she took part in between May and August 2020 in the city of Utrecht.

Sandwiches against viruses

Remembering the first lockdown, almost a year ago, it felt like we were entering a new and uncertain situation. However, we had our energy bars full and our creative potential intact, compared to now. Our lives were turned upside down from one day to the next but at the very least we were faced with some challenges which required mobilizing, thinking out of the box and re-inventing the ways we go about our lives. Back then, numerous initiatives popped up as an immediate response to the new situation providing material or immaterial support to those affected. The contrast between the quietness of this second lockdown and the mobilization of the first one is striking but at the same time creates some space to reflect on the previous period.

While a good two months of quarantine had redefined our lives in an unprecedented way, I got a message from a friend asking if I would be interested in helping out with a solidarity meals initiative. Aiming to relieve vulnerable groups from food precariousness caused by the Corona-crisis, the plan was simple, we would prepare lunch boxes every Monday and Friday at BAK art institute and we would distribute them at Utrecht’s social center ACU. At the time, a group of volunteers had been preparing and giving out 100 dinner meals a day at ACU already for weeks. Based on the demand, expanding to providing lunches as well, seemed to the people involved as the next logical step. The idea was appealing: there is an evident need, there was a structure to support it, the collective Basic Activist Kitchen of BAK, a collective which organized discussions about the politics of food and cooked collective meals during various occasions in the art institute. With their know-how and equipment on board, as long as volunteers were found the project would be ready to kick-off.

Without much hesitation I agreed, I was suddenly found with plenty of time in my hands and I surely wanted to put it in good use. Solidarity meals and food activism of various strands, be it grassroots or implicated in government or other official structures were no news to me. My friend knowing my involvement in social projects/activism and my past experience in food sovereignty initiatives reached out to me, among others, trying to mobilize her networks. In turn, I sent an email to the housing union I am part of – a union of residents who manage a building of 30 living units, typically attracting members of a socially engaged profile- asking whether people were interested in participating. After a chain reaction type of events, a steady group of volunteers was formed, ready to start operations. The group consisted of some members of the housing union, volunteers of BAK and some volunteers from ACU. As Vincent Walstra, PhD candidate of the ‘Food Citizens?’ project discussed in his blog post Impact of Covid-19: Digital food collectives in Rotterdam, digital platforms of communication such as Whatsapp tend to mediate the formation, coordination and operation of such loosely defined, action-oriented groups. Following this trend, our communication and organization was largely Whatsapp-based. Shifts were organized digitally and practicalities were communicated among encouraging emoticons and photos. Every Monday and Friday the cooking team would gather at BAK. While some already knew each other from other initiatives, the majority met for the first time through the project and enthusiasm, eagerness and motivation were ample. These two days of the week were for many of us the most active ones in a quite dull and repetitive quarantine-life.

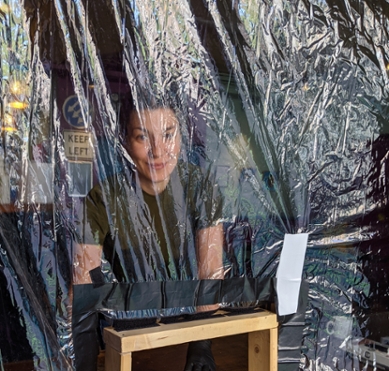

The friendly responsible of the space would let us in and then the cooking would start in the professionally equipped kitchen of BAK. Around noon the distribution team would go by BAK to pick up the lunch boxes some fruit and juices and would head to ACU where the distribution took place. Just like all the steps of the process, preparing food, collecting and distribution were organized with strict hygiene measures. Masks, gloves, a protective plastic panel and social distancing were the measures applied to protect the volunteers and the people who received the lunch boxes. A table would be set up on the front door of the social center as barrier and a sign publicizing the lunch boxes would be put out, on the pavement. Word was already out that we offered lunches since the dinner team had been informing people coming in for their meals and on average we distributed about 20 lunches a day to more or less a stable group.

Much to the volunteers disappointment, the lunch boxes were not as popular as the dinner meal. Casual brainstorming while cooking or while giving out meals revealed the anxiety: ‘We should put photos of our sandwiches on Instagram!’ or ‘How about we tell beneficiaries to spread the word more’. Regardless of the volunteers desires, the reality was that on the one hand having to be at a distribution point two times a day, waiting in line for a meal is simply impractical for many of those receiving the meals and on the other hand , the idea that everyone shares the same eating habits, lunch at 12:30 and dinner at 18:00 pm is just not true.

Nevertheless, the social contact we had with the volunteers and the beneficiaries was in itself a success, as was the ability to provide support to disadvantageous groups. A type of support which extended to friendliness and warm interactions next to material goods. Especially since we were active during the first lockdown where social interactions were scarce. A short talk with people coming in for lunches seemed to make a difference. Thus, next to the material help, a point of reference addressing the most marginalized in the rather gentrified center of Utrecht offered a certain recognition and feeling of visibility in a moment of crisis. A space that opened up for people in need while the whole city and its support mechanisms were shutting down.

The project ended in August 2020 with the idea that the activists’ resources where running out both in terms of energy from the volunteers side and material goods while the responsibility was deferred to the municipality to find a structural solution, as the online article of the Utrechtse Internet Courant reports (in dutch).

Crossing institutional boundaries

What stood out for me in this whole experience, was the infrastructure supporting the project. As mentioned above in the chronology of our small contribution to the city’s solidarity scene, the spaces which were used were the art institution BAK, Basis voor Actuele Kunst and the social center ACU. Both with different history and mission, these two entities managed to create a platform where such types of projects could emerge. How was that possible?

From ACU’s website one reads: ‘ACU is a political-cultural center in the Voorstraat directly in the center of Utrecht. ACU is noncommercial, independent from the municipality’s agenda and fully run by volunteers. ACU has found its niche as is for more than 40 years an integral part of Utrecht’s cultural and political scene’. A legalized squat, remnant of the roaring squatters movement of the eighties and deeply rooted in a tradition of egalitarian politics, direct action and autonomism it is very much expected from a space like this to host solidarity meals. People’s kitchens and solidarity meals (eetcafés and volkskeukens or vokus as they are called in the Netherlands) is what activists of this genealogy have been doing for decades after all. However, one would wonder – and rightfully so- what does an art institute have to do with charitable meals or activism of this kind?

The relationship between art and activism or political discourses has been an established field of study and a well-known debate as often one of the functions of art and artistic practice is to criticize but also figuratively – and quite literally in some cases- ‘paint a picture’ of the wrongs of the contemporary world. Moreover, art speaks to the imagination of people, presents new worlds and possibilities. It is therefore a powerful tool of persuasion and mobilization for affirmative change.

If one would closely look at BAK’s program they would immediately recognize the institute’s commitment to such causes. Furthermore, the idea of bringing together practitioners, artists, activists and thinkers while creating a platform for emerging boundary-crossing projects is evident in many of BAK’s activities. For example, the series BAK, basis voor… was conceived by artist and BAK collaborator Jeanne van Heeswijk as a basis for collaboration and interaction of grass-root organizations, communities and unexpected formations as the playful use of the ellipsis in the series name implies. The last year quite a few individuals and collectives have found shelter in BAK including Extinction Rebellion, refugee women’s organization New Women Connectors and the grass-roots, radical left festival 2Dh5 to name a few. Collectives one wouldn’t expect to meet in a museum or a gallery or an art space somehow make their appearance in BAK.

Like so, the Basic Activist Kitchen, which I mentioned earlier, has turned to be an organic part of BAK which in an opportune moment can introduce topics of food procurement, food waste, solidarity meals, cooking and eating together as a political act in the institute’s agenda and beyond. In a moment of crisis, these actors where able to quickly respond to emerging urgencies and set up projects like the one I participated in, bringing together different people and institutions and the various sets of skills and world views that they bring along.

As far as I could tell, this atypical collaboration of an ex-squat, current autonomous social space, an art institution and volunteers was possible because of the involvement of actors operating in both spaces and the intentional opening up of BAK to collaborations outside the ‘usual, institutional, suspects in the period prior to the pandemic . Activists, organizers and other actors found each other, interacted, bridged their interests and concerns and most importantly built networks of trust and mutual help. By mobilizing those networks, friendly relations and their capacity, our food relief initiative became - apart from a gesture of solidarity towards the disadvantageous groups in the city of Utrecht- an experimentation in overcoming the strict definition of an art institution and its role in city life.

Rather than official agreements or declarations of long-term collaborations these unforeseen joint forces point to a direction of more fluid and flexible institutional work where the meaning of culture as public good translates into a quite tangible form. A definitely interesting development to reflect upon and something to follow in the future!

This blogpost is not part of the Food Citizens? project research but a friendly contribution to the ongoing dialogue on food activism and solidarity initiatives the Food Citizens? blog fosters.

1 In particular the period between September 2019 and January 2020 where the exhibition/trainings Trainings for the not-yet took place. https://www.bakonline.org/program-item/trainings-for-the-not-yet/