Governing the commons: What we can learn from each other's (not so) foolish disciplines

PhD candidates Vincent Walstra and Leen Felix in dialogue

What happens when you put together a Cultural Anthropologist and an Environmental Geographer, no-one ever asked. But it happened anyway when we, Leen Felix, PhD at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, working in the European TERRANOVA project as Environmental Geographer, and Vincent Walstra, Cultural Anthropologist, doing a PhD at Leiden University, working in the ERC ‘Food Citizens?’-project, met each other. As a couple we tend to bother each other with our thoughts. Surprisingly often, our qualitative micro study of culture and quantitative macro study of landscapes cross topics. In this interdisciplinary blog we present a snapshot of the friction between our bottom-up and top-down perspectives. The vastness of information in the contemporary globally interconnected world often forces citizens, politicians, businesspeople, and scientists alike, into a narrow-minded, even stubborn simplification of a complex reality, refraining from challenging their own worldviews. This blog will not give answers to how to combine qualitative and quantitative methods in an optimal mode of governing. Instead, the following dialogue illustrates a situation in which we often find ourselves, as two young, stubborn academics picking each other’s brains about a shared topic of interest, in this case, ‘the commons’. By listening to and questioning each other’s alien visions, we broaden our understanding as we find ways to grasp the complexity of topics we thought we understood.

Leen: “I see you are reading the tragedy of the commons (Hardin 1968), that’s an interesting read!’’

Vincent: “Yep, I’m reading it for work. I already found so many ways in which it is relevant.’’

L: “That’s a coincidence! I’m also using the theory in my work.’’

V: “It intrigues me that 60 years after this was published, sustainability issues still seem to essentially come down to mismanaged commons. Don’t they ever learn?!’’

L: “I know, In my job I try to view nature as a common good, and it’s painful to see politicians refusing to think about long term sustainability. If we continue like this there will be nothing left of our beloved natural common.”

V: ‘‘Agree. That’s why I get so inspired by the people I encounter during my field research. Take for instance this project that revives local biodiversity by cooperatively maintaining a wildlife-friendly farming project. Pigs and chickens roaming around in forests like they should, foxes and geese visiting the farm, and flowers for birds and insects whilst it is productive at the same time. And they are growing so fast, I think we should farm like this everywhere!’’

L: “Oh what? that’s not at all how I see it. I would say that, looking at the growing demands for food, if we still want to preserve some space for nature, we need to put aside this ideal of “farming the old way” and get real with sustainably producing as much as possible food in as little as possible space.’’

V: “I’m sorry, but that just doesn’t feel right.’’

L: “I get that, but do you want your feelings to be the reason there is no real nature anymore in 50 years time? No matter how wildlife-friendly farms are compared to industrial farming, they are still nowhere near the wild nature that those plants and animals would prefer. Those pristine habitats are slowly disappearing from the world. The way I see it, wildlife-friendly farming is indirectly contributing to this, because it generally causes a loss of yield which is compensated with agricultural expansion elsewhere.’’

V:“Of course not, and it’s an interesting point, but do you really want your calculations to deny people who care about nature to have some of it close to their homes? Besides, many of them see it as an opportunity to familiarize their children, our next generations, with the natural world and the process and costs of food production.”

L: “Well, no… I guess I never thought about it that way.’’

V: ‘‘To be honest, I realize I was too narrow-minded myself when I said we should take this wildlife-friendly farming as the new standard.’’

L: “Okay, I’d say then that I still want to see a general pattern of intensification, but there needs to be space for the needs and values of the locals, whether they are farmers or admirers of traditional agricultural landscapes.’’

V: ‘‘Yes, and maybe I will reconsider my romantic vision of wildlife-friendly farming for all. If it is a more intensive form of farming that matches the needs and values of locals, they are actually indirectly giving other regions space to preserve or even restore nature. So nature-lovers, often demonising intensive farming, might to some extent even be grateful for it.’’

L: “So then it is all about finding that balance between cultural needs for biodiversity and large scale land use optimisation for biodiversity. But it is interesting that there is an imbalance in the first place, since it seemed as if we were both looking for the same sustainable goal. How could we explain that?’’

V: “Let’s see. the Tragedy of the Commons, which I am reading here, explains that on a local scale people acting out of self-interest will over-exploit the common good (Hardin 1968). Now, it appears that this tragedy is recurring at larger scales. Group members at a certain scale are trying to manage a shared resource according to their common interest. But this group can then simultaneously be a member of a larger scale group that shares a different common resource. Similarly as on the local scale, issues of self-interest will arise and the need for governance is inevitable.’’

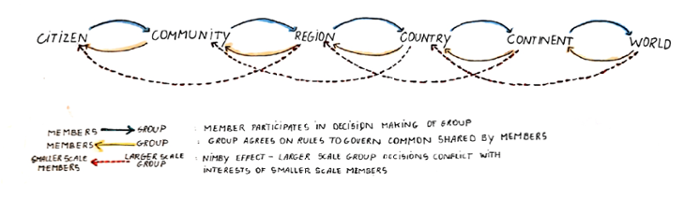

L: “I see what’s going on here. We are dealing with the same issue, but talking about different scales of governance. Let’s see what this looks like if I draw out what we have been saying.’’

Leen takes out a notebook from her bag and starts drawing.

V: “That looks good!’’

L: “Yes, and Elinor Ostrom (1990), known for her research on governing the commons, did indeed talk about common governance at various scales, but there’s more to it. There seems to be a conflict between managing the commons at different scales. Since each group has to govern its own commons while also responsibly sharing larger scale commons with other groups, a conflict between governing the commons at different scales seems to be imminent.’’

V: “Exactly. And when smaller scale members find their own situation directly affected by measures following from larger scale agreements, there can be a sort of Not In My Backyard (NIMBY) reaction. [Adding the red arrows to the drawing] I think that key to this drawing is that there is no arrow complementary to this “NIMBY-effect”. Members at smaller scales were not directly included in the decision making at larger scales. Therefore a sense of disownership may grow into a feeling of unjustness, creating bottom-up resistance.”

L: “A tragedy of the tragedy of the commons! [Laughs]. Maybe this happens because there is a lack of awareness that these agreements, despite conflicting with their direct interests, generate common benefits.”

V: “Or maybe, decisions at a larger scale made it impossible for groups further down the scale continuum to match the needs of their members.’’

L: “Probably both are true. This looks a lot like our disagreement at the start of our own discussion. When I was looking from a top-down perspective, whilst you were wearing your bottom-up glasses. I guess this happens not only to us.’’

V: “You are right, here we see the difference between our two disciplines’ points of view, reflected in society at large.’’

L: “True. So how could we combine these perspectives and look for possible solutions to this ‘tragedy of the tragedy’?’’

V: “Hmm, well the nature of topics treated at each scale is very different. At smaller scales, governing the commons might be about dividing pastures amongst herdsmen, like in Hardin’s example, but at a larger scale topics become more abstract and long term, like climate change. I think being aware that these topics vary across scales of governance, and reflect differences in the broader responsibilities of each, is already a big step forward.”

L: “Absolutely! And therefore, they require a different approach. Decision making at these different scales will probably rely on different sources of knowledge that are best suited for these topics.’’

V: “I see what you mean. In my work, I use this theory called social innovation (see for instance Moulaert 2009), which looks at innovation from the bottom-up. What’s interesting is that it specifically talks about local and regional development. At these scales, it will probably pay off to support citizen’s initiatives that answer pragmatically to required transformations. But I think it is fair to say that the bigger the scale, the harder this becomes.’’

L: “That’s right! And vice versa, the calculations made in my work that aim to influence continental or global scale agreements are becoming better and better at taking all sorts of environmental variables into account, but they will never be able to reflect the cultural complexity within a specific societal context.’’

V: “Okay, it seems that we can agree. The crux is then to accept that the interrelatedness of governance at different levels inevitably creates conflicts, and realize that black-and-white thinking hampers us in effectively navigating them. In small scale governance, more awareness about larger scale responsibilities will eventually result in less resistance to the governing limitations imposed by larger scale agreements.’’

L: “You are right. And I think it is crucial that on larger scales it is communicated clearly why their rules are imposing limitations on smaller scales of governance. Besides, on a smaller scale, people should be given the freedom to implement these unpopular top-down regulations in accordance with the local needs and values, allowing space for deliberative forms of governance like social innovation.’’

V: “Exactly! Remember when we started this discussion? For a moment I thought that you were nuts, telling me that we need to intensify agriculture whilst all around me I hear people say agriculture needs to become more organic and wildlife-friendly.’’

L: “Haha I know. For a second I thought you had lost your mind, ‘how many planets does this guy think we can cultivate?’ I found myself wondering. But now that we’ve explained each other’s point of view, it seems that we both have an argument to make, and they do not entirely juxtapose each other.’’

[A man walking a dog passes by and notices Leen and Vincent] Man: “I could not help but overhear your conversation, but this tragedy of the tragedy you mentioned, it is not so tragic at all. Polycentric governance (Nagenda and Ostrom 2012; Ostrom 2010) is what you are looking for. You guys should read up on it.” [But the dog notices another dog and drags the man away before he can explain further]

V: “Oh, interesting! I am certainly going to. Anyway, for me it has been a valuable lesson, I wonder if we should share this conversation with other people, what do you think?’’

L: “Sounds like a good idea. How about we write a blog about it?’’

V: “Awesome! Let’s get to it.’’

References

Hardin, Garret. 1968. ‘’The Tragedy of the Commons,’’ Science, 162:1243-1248.

Moulaert, Frank. 2009. "Social Innovation: Institutionally Embedded, Territorially (Re)Produced," in Social Innovation and Territorial Development by Diana MacCallum, Frank Moulaert, Jean Hillier, and Serena Vicari Haddock (eds.), pp. 11-23.

Nagendra, Harini, & Ostrom, Elinor. 2012.‘’Polycentric governance of multifunctional forested landscapes,’’ International Journal of the Commons, 6(2):104–133.

Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, Elinor. 2010. "Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems," American Economic Review, 100(3):641-72