Field School 2018: Introduction to the Gallina Landscapes of History Project

Between June 1st and July 1st, Dr. Lewis Borck along with several students from Leiden University conducted fieldwork in the American Southwest in the context of the Gallina Landscapes of History Project.

Gallina Landscapes of History 2018

By Lewis Borck

This project has been ongoing for about a decade in one form or another, although this is the first year with partner organizations (Santa Fe National Forest Service) and research projects (Nexus1492), as well as interns. Furthermore, the project was lucky to have some help from SWCA in the form of equipment and time. All in all, it’s a big, opening year for renewing research and connections in the San Juan region and on the archaeology of the Gallina region.

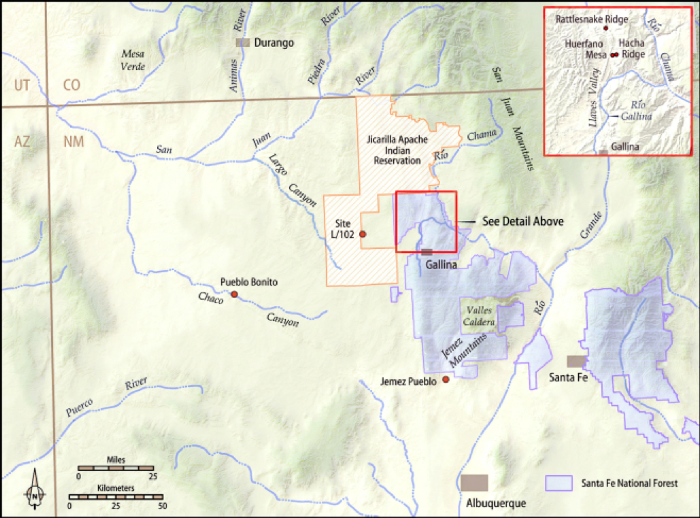

As a few of you know, in the American Southwest, I focus on the Upper/Lower San Juan and most of the southern Southwest, including across the border in Mexico. I also work, in the Caribbean with the Nexus 1492 project. These regional focuses may seem quite broad, but for the type of analyses and methodology I do (ceramic, spatial, and network), this sort of "30,000 foot/10,000 meter" overview helps me sketch together broad patterns that might not be apparent otherwise.

The students and my volunteer assistant who signed up for this year knew, or at least now know, much of this background. They also signed on to join a public-oriented field school, which means a portion of their training is in public interaction and outreach. This type of collaborative and partnered project can be extremely meaningful.

In particular, let’s talk a bit about what it meant for this year.

First the downside. We lost our field site the day before the students showed up. Literally. This had nothing to do with us, and wasn’t the fault of our partner organization (the Santa Fe National Forest). In fact, the SFNF was incredibly helpful throughout this whole process. Instead, us losing our research area had everything to do with human increased climate change leading to one of the worst droughts in recorded Southwestern history. That is a blog post on its own, but basically massive agricultural and pastoral activities in the American SW starting in the 1800s led to a dramatically lower groundwater table (and thus arroyo downcutting). It’s just gotten worse since then. Cut to 2018, where there had basically been zero precipitation (rainfall or snow) in northern New Mexico since December 2017 until a weekend storm in mid-June 2018. Zero.

The northern Southwest, at high elevations, is prone to naturally caused wildfires from lightning strikes in even the best weather conditions, but with spring and then early summer winds kicking in and some of the lowest moisture conditions ever recorded, public land managers in multiple agencies (Bureau of Land Management, National Forest Service, State and County lands, etc.) implemented Stage 2 fire restrictions. Essentially, people were still allowed to use these public lands, but only without using fire in any way (propane stoves are okay). The entire U.S. celebrated Memorial Day weekend a few days before the students arrived, and with it, there was an explosion of visitors to the Santa Fe National Forest. This is normal. One of the primary uses of public lands is for recreation in one form or another. But along with that visitation came a rash of untended campfires. Because of the conditions, even tended campfires (banned because of the Stage 2 restrictions), could quickly get out of control and start a large wildfire. Untended ones are much worse. Over that weekend, the SFNF put out around 125 untended fires. The supervisor for the SFNF, based on that, decided to go into Stage 3 closure. This meant all of the public, including non-essential NFS workers, contractors, etc, were not allowed onto Forest Service lands.

Again, this all happened the day before my students arrived. Understandably, there was a bit of stress and frantic scrambling on my part as I tried to salvage a research project with very specific aims and types of sites needed to fulfill those aims. In the end, this became another learning experience for the students as they were able to watch and see just how much archaeology depends on networks of archaeologists, archaeological organizations, and community connections and interest.

By the end of that first week, the students had met with a number of other field schools, gotten tours of multiple archaeological sites whose inhabitations ranged from 2000 years ago to just about 300 years ago, and driven with me to a lot of meetings that probably seemed like casual conversations as we tried to salvage the season. An offer to excavate at another project’s site eventually came through as well, but by that time, we’d happily found an amazing archaeological settlement on private land in the Llaves valley that perfectly fit our research goals.

Student blogs

Since this field school is public-oriented, the students were required to write blogs about their experiences throughout the fieldwork. This formed part of their training in public interaction and outreach. This has resulted in interesting blogs focused on a highly diverse and current range of topics.

These blogs have been posted on the Gallina Landscapes of History website. Take a look, and see what our students have been up to this summer! If you want to look at any posts on social media, you can search for #GLoH2018.