Considerations of a map-maker

As a visualisation expert in a project focused on Caribbean archaeology, a significant part of my work consists of making maps. They might be maps of one excavation area, an entire island, or a larger region. They might show ceramic assemblages, settlement patterns, or cultural heritage. They might be used to visually explore a dataset and uncover new patterns, to communicate established results in a scientific publication, or to inform the general public about ongoing work. The one thing they all have in common is that they represent geo-referenced data (information associated with specific locations).

Advantages of Algorithms

Since I am a PhD-student in computer science, I do not design these maps by hand. My aim is to develop algorithms (logical instructions that can be given to a computer) to do some of the work for me. The main advantage of an algorithm (compared to manual work) is that it can be reused. This allows us to efficiently visualize multiple different datasets, or to quickly redraw a map whenever the input data have changed. The tradition of drawing maps by hand is many centuries old, but automated map design has been studied for only a few decades now. It is challenging to translate all the considerations of a human map-maker to a computer program, and there are many open problems left to solve in this area.

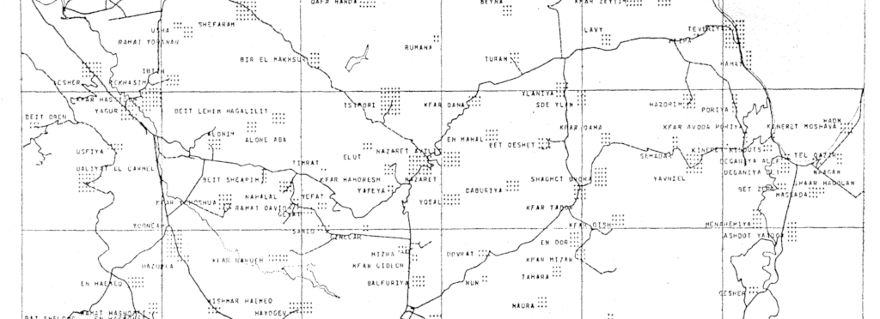

First map with automated label placement, as published by Yoeli (1972)The process of visualising geo-referenced data can be divided into multiple steps: (a) making a background map, (b) designing some icon, glyph, or label to represent the information for each element, (c) selecting what elements should be shown on the map, and (d) assigning each icon or label a position on the map. In my research I focus on automating the last step, positioning a given set of labels on the map. In computer science this problem is known as label placement.

In 1972, Pinhas Yoeli was the first to propose that the label placement problem could be solved with the help of computers. His seminal paper entitled “The logic of automated map lettering” laid the foundation for many of the approaches that were developed afterwards. As is common in computer science, Yoeli initially studied a simplified version of the problem. One of the restrictions was that all labels had to be placed horizontally. Printing devices at the time were not capable of printing letters in different orientations, and Yoeli did not think it would be worth the time and effort for people to develop such a thing.

Result of an algorithm that removes the overlap between labels“It is, of course, theoretically possible to construct automated output devices which could place curved names in precisely the same manner as when being done manually. […] We wonder, however, if the necessary expertise and effort involved would be justified economically.” Pinhas Yoeli, 1972.

People sometimes wonder why I would persist in developing an algorithm for something that human map-makers are able to do so well. When asked that question, I always think of this quote. Less than fifty years ago, an expert in map design thought it would be a wasted effort to develop a machine that can print text at different angles. He argued that since this was not needed often, it could just be done by hand. Nowadays, even a basic home printer can print photographs in full colour and high quality. So even if my algorithms cannot beat manual designs yet, I am optimistic as well as curious about the future.

By Mereke van Garderen