Why we need to co-create knowledge for sustainability – and why this is easier said than done

Recent debates on energy transitions and poverty illustrate the social ecological complexities of sustainability problems. These cannot be tackled by single academic disciplines – nor by academics alone. In this blog, Marja Spierenburg reflects on the need for, and challenges of ‘transdisciplinarity’.

Sustainability problems as ‘wicked’ problems

Most sustainability problems are complex, and solutions have to take into account the different social and economic driving forces causing the problems, but also the linkages between what happens at local levels, and how this is connected to global trends or other places in the world. Furthermore, solutions may result in different impacts on different groups in society.

Impact of electric cars and bikes

Take for example the growing popularity of electric cars and bikes in the Netherlands – wonderful contributions to the reduction of our carbon footprints, or not? E-bikes and cars are expensive, so they are not accessible to everyone, and plans to phase out fossil fuels may impact on the mobility of poorer Dutch citizens. In addition, e-bikes and e-cars require powerful rechargeable batteries, which increases the demands for metals such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel.

Mining these metals may result in serious environmental damage, but also in the displacement of local residents in Latin America and Africa, either directly when their lands are taken over by mining companies – often without compensation – or because pollution renders agriculture and livestock husbandry impossible. Working in the mines is often dangerous and not well-paid, and does not compensate for the loss of land.

Some minerals can fuel armed conflicts

In some cases, such as cobalt mining in the Congo, the presence of certain minerals may also fuel armed conflict. Yet, the EU is very reluctant to integrate those metals crucial for the production of e-bikes and cars into legislation on responsible mining, as this would interfere with the EU objective of reducing fuel dependency. Such trade-offs may not be easy to predict or address.

Why we need to co-create knowledge for sustainability transformations

Given the complexities presented above, it seems only logical for academics from different disciplines to team up to develop solutions to foster sustainability together. Even better, why not include those who are directly affected by either the problem or its proposed solution, and work together to discover what local knowledge is available, and which knowledge gaps need to be addressed by academics in cooperation with societal actors? Such an approach, referred to as co-creation of knowledge, or transdisciplinarity, is increasingly promoted by research funding agencies, who may even make it a condition for research funding.

Importance of local knowlegde and participation

Anthropology and development sociology seem to be particularly valuable in establishing processes of co-production, and fostering the inclusion of the perspectives and knowledge of societal actors in sustainability research, as these disciplines have a history in calling attention to the importance of local knowledge and participation. Furthermore, within our disciplines we have been reflecting quite extensively on how knowledge is almost always co-created by researchers and research participants.

Ethnographic methods involve intensive interactions with research participants, who reflect with us on our questions, and add questions of their own. These interactions, in turn also require us to reflect on how our own position vis-à-vis our research questions and research participants influences our research.

Challenges in the process of co-production

In practice, however, working across disciplines and with societal partners is far from easy, and requires long-term engagement. Researchers coming from different disciplines have different ways of engaging with theory and data. Constructing models of climate change with a range of biopsychical variables and feedback loops requires different data and is based on a different view on the relation between theory and reality than an ethnographic study of how people experience and respond to climate change.

Understanding between researchers from different disciplines is imporant

Researchers also need to learn to understand one another. When ecologists talk about social ecological systems, they refer to dynamic systems with all kinds of feedback loops, tipping points and leverage points for change. Anthropologists, on the other hand, often fear that the concept of a ‘system’ refers to something static and coherent, which does not accommodate the dynamics and ‘messiness’ of people’s daily experiences that we encounter when we study culture and human-nature relationships. Elaborating a joint research programme while being trained differently requires long-term engagement to develop a thorough mutual understanding.

Engaging different partners is a balancing act

Adding societal partners in the mix further complicates matters. Which partners are included, or excluded, which ones are not on our radar? Engaging with a wide range of actors and stakeholders, such as policymakers, residents, private sector companies, is a balancing act. Even when they agree to work together to try and find solutions to sustainability problems, they may have very different ideas about the end goals and the ways to get there. A complicating factor is that between – but also within – these groups of actors, different interests may prevail, as well as unequal power relations, as the following example shows.

Power and inequality: wildlife ranching in South Africa

In a research project I coordinated together with colleagues in South Africa, we were confronted with highly unequal relations between the different research participants. We studied the socio-economic impacts of shifts from conventional farming to so-called game farming, i.e. the conversion of crop or livestock farms, mainly owned by white farmers, to wildlife production. These conversions were supposed to contribute to biodiversity through the creation of wildlife habitats, and to local economic development through tourism development (game viewing as well as hunting), which allegedly resulted in more employment opportunities. We wanted to know what the impacts of the conversions were on – mainly non-white – farm workers, for whom the farms are not only their workplace, but also their home. In some cases, families had been living and working on the same farm for generations.

Engaging farm workers

When we discussed our research plans with game farmers and their lobby organization, they were enthusiastic, since they believed our research would confirm their ‘win-win’ narrative. However, when we also proposed to invite rural development organizations representing farm workers, most game farmers objected, saying that there was no need to involve them, let alone the farm workers themselves, as the lobby organization could provide us with ‘the right data’ on the number of jobs created. Farm workers were not considered knowledgeable on the ‘wildlife industry’ and its impact on development. Ensuring farm worker participation in our research was a challenge, as we had to ask permission from game farmers to visit the workers on their farms – though we managed to find a way around that by engaging with them in the townships where they would frequently visit family members.

With our team we conducted almost 300 interviews with game farmers, farm workers and dwellers, government officials, and land rights and labour activists, and conducted ethnographies on eleven game farms in the Eastern Cape and Kwa-Zulu Natal. One of our findings was that in most cases farm conversions result in an actual loss of employment possibilities, except at the very high-end luxury ‘eco-tourism’ game farms.

Many game farms consist of an amalgamation of several farms, with either investors buying up land or farmers pooling their land to create larger habitats for wildlife. This increase in scale often results in smaller workforces, and much of the work in the tourism is seasonal. In addition to losing their jobs, many farm workers and dwellers also lost their homes on the farms, ending up in informal settlements or squatter camps throughout the region. These findings did not go down very well with the game farmers and their lobby organization. At the multi-stakeholder meetings we organized to discuss the present and future of game farming, we battled to create space for farm worker perspectives, as we discuss in an open access publication in Ecology and Society.

We were not naïve, when we started the project, we had no illusions that we would be able to solve the problems of the farm workers, as these are rooted in colonial and apartheid legacies of land dispossession and centuries of discrimination. We had hoped, however, that we could put the plight of the farm workers on the agenda of government officials and policymakers in post-apartheid South Africa.

However, desperate about the staggering unemployment rates and high levels of poverty in their regions, they were very reluctant to abandon the win-win-narrative. Changing these narratives takes long-time engagement, and it is only now, after our project officially came to an end, that we are approached by government officials to help them reflect on their assumptions.

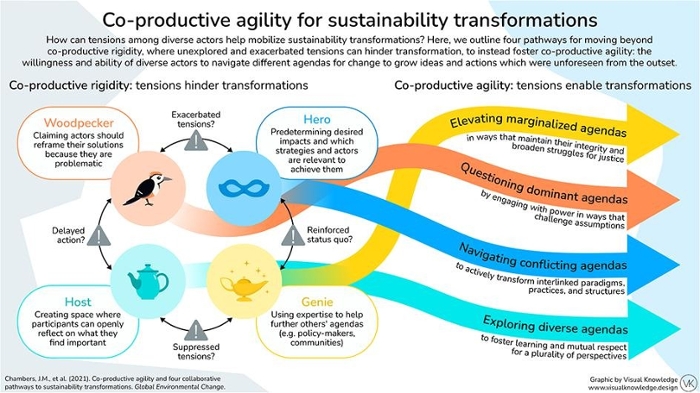

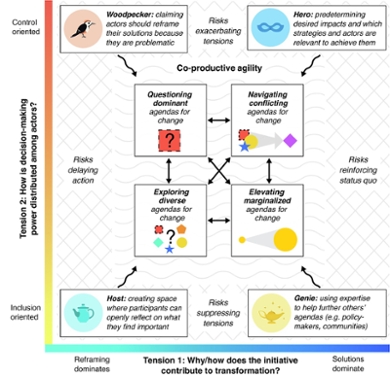

Dealing with tensions and power relations – co-productive agility

Our case was one of 32 co-production initiatives we analyzed with a group of colleagues (see Chambers et al. 2022). This analysis showed that in co-production initiatives, there is often a tension between the need for researchers (and their partners as well) to demonstrate the relevance, impact, and efficiency of research projects, versus facilitating co-production processes, which requires exploring and redefining how sustainability problems are understood by the various actors involved.

The latter often takes more time, and also touches upon an important question about how the decision-making power is distributed among the actors. Co-production requires dealing with different, and often seemingly contradictory agendas by different actors. These agendas are shaped by the knowledge, values and goals of the various actors – including the researchers themselves – which they use to support their claims about what kind of change is needed and how this is to be achieved.

Inclusive transformation requires a willingness from actors to explore these different agendas, and regard them as part of the inherently complex interdependencies which are part of sustainability problems, rather than as competing interests. In the paper, we refer to this as co-productive agility, as it requires a lot of maneuvering and balancing. While it is not easy to organize, inclusive co-production is a prerequisite for transitions which are both ecologically and socially sustainable.

Practical guidebook

To provide interested parties with some insights and practical exercises to foster co-productive agility, some of the authors involved in the research paper have developed a practical guidebook which is available here.