Summer School in Languages and Linguistics

Program 2024

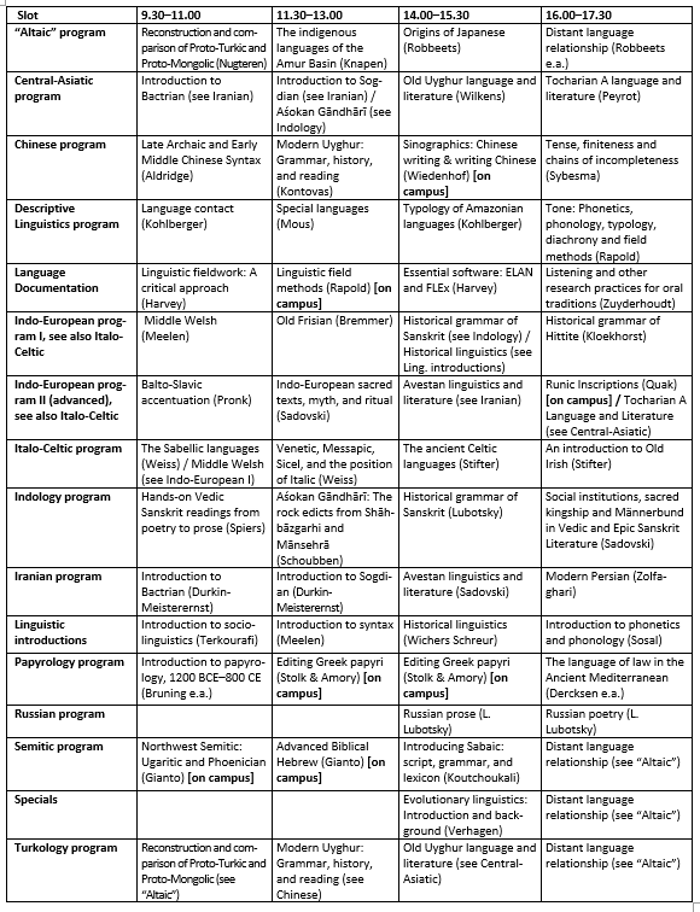

Most of the courses will be taught in a hybrid/mixed manner. This means that most of the courses will be given on campus as well as online. Some courses will only be taught on campus or online, this will be specified for those courses.

Below you will find the course descriptions per program.

“Altaic” program

Slot 1

Lecturer: Hans Nugteren, Göttingen

This course is an introduction to the reconstruction of Proto-Turkic and Proto-Mongolic. Turkic and Mongolic are two languages families which are geographically extensive but of limited internal diversity.

The two families feature many similarities in typology and lexicon, which has led to them being viewed as two branches of the so-called Altaic languages (together with Tungusic but excluding Korean and Japanese they may be referred to as ‘Micro-Altaic’). Some specialists consider the similarities to be mainly the result of centuries, possibly millennia, of contact, while others are convinced they are due to a common origin.

We will discuss these two language groups as separate entities as well as the similarities and differences between them, with the focus on phonology and lexicon. It is not a goal of the course to determine whether the two families have a common origin.

Topics to be covered include:

- History of the Field (including so-called Altaicists and Anti-Altaicists)

- Turkic and Mongolic Family Trees

- Sources, Methods and Principles

- Contributions from Tungusic, Khitan and Hungarian

- Turkic, Mongolic and ‘Altaic’ Typology

- Proto-Turkic Phonology

- Proto-Mongolic Phonology

- Comparison of the Two Systems

- Reconstruction of Individual Lexemes

- Turkic-Mongolic Comparison

- Evaluating Similarities and Differences (Sound Laws, Borrowing and Coincidence)

Level

Previous knowledge of one or more Turkic or Mongolic languages will be useful but not required.

Requirements

During the course it will be necessary to review the discussed topics. There will be some small reading assignments. A written exam after the course is optional.

Text

Course documents will be provided; no textbook is required.

Slot 2

Lecturer: Martijn Knapen

The Amur River and its tributaries form much of the easternmost section of the Russo-Chinese border. The Amur reaches the sea at the Strait of Tartary, which separates Sakhalin Island from the Asian continent. To the south of Sakhalin lies the Japanese archipelago. National borders in this region remained unfixed until well into the twentieth century, as the Chinese, Japanese and Russian empires and their successor states claimed possession to all or parts of the Amur Basin and Sakhalin. This region’s indigenous peoples speak languages that primarily belong to two unrelated linguistic lineages, Tungusic and Amuric, which will be the focus of this course. Of the Tungusic languages, Manchu might be the most famous, as the native language of several emperors of the Qing dynasty, but it represents just one branch of up to four. Amuric includes the Nivkh varieties spoken along the Lower Amur and on Sakhalin, from which comes “Nivkh”, the name more commonly applied to this language family.

Partially due to the history of the Amur Basin, descriptions of its indigenous languages have not commonly been published in English. This course aims to increase the accessibility of this field. Taking a historical linguistic perspective, it will provide overviews of several Tungusic and Amuric languages, focusing on four overarching themes: reconstruction (phonology and morphology), classification (a heavily debated issue within the study of Tungusic), contact and migration. Students will learn to produce and evaluate reconstructions of Proto-Tungusic and Proto-Amuric. They will also learn how to analyse texts written in the languages that descend from them. Upon completing this course, students will have gained a strong foundation to continue their studies on the indigenous languages of the Amur Basin or Northeast Asia more generally.

Level

Knowledge of core linguistic concepts related to phonology and morphology is preferred, while basic knowledge of historical linguistic methodology is recommended but not required.

Requirements

There will be a short assignment after every class. Please set up an account at https://manc.hu/ beforehand.

Recommended (non-mandatory) literature

- Janhunen, Juha. 2010. ‘Reconstructing the Language Map of Prehistorical Northeast Asia’. Studia Orientalia, 281–303.

- Janhunen. 2016. ‘Reconstructio Externa Linguae Ghiliacorum’. Studia Orientalia 117: 3–27.

- Janhunen, Juha A. 2012. ‘The Expansion of Tungusic as an Ethnic and Linguistic Process’. In Recent Advances in Tungusic Linguistics, edited by Lindsay J. Whaley and A. L. Malʹchukov, 5–16. Turcologica, Band 89. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Sasaki, Shiro. 2016. ‘A History of the Far East Indigenous Peoples’ Transborder Activities between the Russian and Chinese Empires’. Senri Ethnological Studies 92 (March): 161–93. https://doi.org/10.15021/00005996.

- Wang, Chuan-Chao, and Martine Robbeets. 2020. ‘The Homeland of Proto-Tungusic Inferred from Contemporary Words and Ancient Genomes’. Evolutionary Human Sciences 2: e8. https://doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2020.8.

- Whaley, LJ, and SA Oskolskaya. 2020. ‘The Classification of the Tungusic Languages’. In The Oxford Guide to the Transeurasian Languages, edited by Martine Robbeets and Alexander Savelyev, 81–91.

- Zgusta, Richard. 2015a. ‘3 Sakhalin Island: Nivkh’. In The Peoples of Northeast Asia through Time: Precolonial Ethnic and Cultural Processes along the Coast between Hokkaido and the Bering Strait, 70–103. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004300439.

- Zgusta, Richard. 2015b. ‘4 Lower Amur Valley: The Amur Complex (Nanay, Ulcha, Orochi, Udehe, Ulta)’. In The Peoples of Northeast Asia through Time: Precolonial Ethnic and Cultural Processes along the Coast between Hokkaido and the Bering Strait, 104–64. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004300439.

- Zgusta, Richard. 2015c. ‘5 Amur and Okhotsk Tungus (Negidal, Eastern Ewenki, Okhotsk Ewenki)’. In The Peoples of Northeast Asia through Time: Precolonial Ethnic and Cultural Processes along the Coast between Hokkaido and the Bering Strait, 165–214. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004300439.

Slot 3

Lecturer: Martine Robbeets

This course is concerned with the early origins of the Japanese language. It begins by exploring a number of previously proposed affiliation hypotheses but it mainly focuses on the genealogical relatedness of Japanese with Korean and Altaic — i.e., Turkic, Mongolic and Tungusic— languages. Discussing the most pertinent issues standing in the way of a consensus, it summarizes correlations in basic vocabulary, phonology, morphology and typology between the languages concerned. The validity and credibility of the linguistic findings is enhanced by multiple lines of evidence, integrating genetics and archaeology in the course. Admitting that numerous properties shared between Japanese, Korean and Altaic languages can be accounted for by prehistoric borrowing and addressing recent criticism against affiliation, this course nonetheless presents a core of reliable evidence for the classification of Japanese as a “Transeurasian”, aka (Macro-)Altaic, language.

Course schedule

Week 1

| Monday | The Japanese language: historical comparative research history |

| Tuesday | Japanese and the Korean language |

| Wednesday | The Altaic languages |

| Thursday | How to establish language relatedness? |

| Friday | Lexical evidence |

Week 2

| Monday | Morphological evidence |

| Tuesday | Japanese and the Transeurasian structural type |

| Wednesday | Linguistic inferences about human prehistory |

| Thursday | Triangulation: integrating linguistics with archaeology and genetics |

| Friday |

Conclusion: evidence and counter-evidence |

Requirements

Knowledge of Japanese and/or other Transeurasian languages is appreciated but not required.

Some background in historical comparative linguistics is useful but not mandatory.

Below are publications underlying this course written by the by lecturer. These are meant as further readings but they are not mandatory.

Publications by lecturer underlying this course (Non-mandatory readings)

- Robbeets, Martine (2005). Is Japanese related to Korean, Tungusic, Mongolic and Turkic? (Turcologica 64.) Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Robbeets, Martine (2015). Diachrony of verb morphology: Japanese and the Transeurasian languages. (Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs 291) Berlin: Mouton-De Gruyter.

- Robbeets, Martine (2017) Austronesian influence and Transeurasian ancestry in Japanese: A case of farming/language dispersal. Language Dynamics and Change 7(2): 1-42.

- Robbeets, Martine (2020) The typological heritage of Transeurasian. In: Robbeets, Martine, and Savelyev, Alexander (eds.) The Oxford Guide to the Transeurasian Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 127-144.

- Robbeets, Martine, Remco Bouckaert, Matthew Conte , et al. (2021) Triangulation supports agricultural spread of the Transeurasian languages. Nature 599: 616-621. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-04108-8

Slot 4

Lecturers: Martine Robbeets, Jesse Wichers Schreur, Tijmen Pronk, Abel Warries, Hilde Gunnink, Marijn van Putten

Distantly related languages are languages that are grouped together into language families although their postulated relationship has not been conclusively demonstrated. The distance between these languages is mostly to be understood in a chronological sense as they commonly trace their alleged origins back over more than eight thousand years. In this course, we discuss the methods for establishing kinship among distantly related languages and we evaluate some of the major disputed proposals of distant kinship, such as Altaic, Caucasian, Indo-Uralic, Nilo-Saharan, Niger-Congo, Afro-Asiatic, etc. From heated discussions on distant language relationship, it becomes clear that there is considerable confusion about the methods linguists use for demonstrating family relationships. This course rests on the well-grounded foundation of traditional comparative historical linguistics to assess proposals of distant language relationship.

Course schedule

Week 1

| Monday | Methodology (Robbeets) |

| Tuesday | Altaic (Robbeets) |

| Wednesday | Altaic (Robbeets) |

| Thursday | Caucasian languages (Wichers Schreur) |

| Friday | Caucasian languages (Wichers Schreur) |

Week 2

| Monday | Indo-Uralic (Pronk – Warries) |

| Tuesday | Languages of Africa (Gunnink): Niger-Congo, Nilo-Saharan, Khoisan |

| Wednesday | Languages of Africa (Gunnink): Niger-Congo, Nilo-Saharan, Khoisan |

| Thursday | Afroasiatic (van Putten) |

| Friday | Afroasiatic (van Putten) |

Central-Asiatic program

Slot 1

See Iranian program.

Slot 2

Introduction to Sogdian: see Iranian program

Aśokan Gāndhārī: see Indology program

Slot 3

Lecturers: Jens Wilkens

This introductory course focuses on presenting an outline of Old Uyghur grammar on the one hand, and it aims at explaining the structure of this language by means of using different text examples on the other. We will analyze reading examples from the first lesson onwards. Participants will quickly familiarize themselves with the typological features of Old Uyghur. The main focus will be on inflectional morphology and word formation.

The course pinpoints the importance of Old Uyghur as one of the main vernaculars of the “Silk Road” for Turkic and Central Asian studies.

Old Uyghur texts are also of great importance from the point of view of religious studies. Buddhist works dominate, but unique Manichaean sources have also been preserved. A few texts from the Church of the East formerly known as Nestorianism have also been preserved.

Course outline

- Old Turkic and Old Uyghur

- Sources

- Writing systems

- Phonology

- Morphology: nouns

- Morphology: pronouns

- Morphology: particles

- Morphology: finite verbs

- Morphology: participles and converbs

- Basic syntax

Level

Background knowledge of or competence in Old Uyghur or any other Turkic language is welcome, but not necessary.

Requirements

There will be short daily homework assignments and a take-home final exam (for additional ECTS points).

Text

Course documents will be provided; no textbook is required.

Slot 4

Lecturers: Michaël Peyrot

This course is an introduction to Tocharian A language and literature. Tocharian A, an Indo-European language from NW China from the 7th to 10th centuries CE, is generally less studied by Indo-Europeanists than the closely related Tocharian B. Yet the language definitely deserves to be studied in its own right: it is typologically more innovative than Tocharian B and preserves important complements to the Tocharian lexicon. Furthermore, it offers some of the best pieces of Tocharian Buddhist literature. In the first week, Tocharian A morphology will be introduced, together with selected first readings. In the second week, the focus will shift to reading. The reading will include passages from the Maitreyasamiti-Nāṭaka, which was translated into Old Uyghur as the Maitrisimit. The choice of the Maitreyasamiti-Nāṭaka passages will be coordinated with the readings in the Old Uyghur course so that parallel passages can be compared.

Level

No previous knowledge of Tocharian is required, though it will be helpful.

Requirements

There will be short daily homework assignments and a take-home final exam (for additional ECTS points).

Text

Course documents will be provided; no textbook is required.

Chinese program

Slot 1

Lecturers: Edith Aldridge

This course provides an overview of the syntax of Late Archaic Chinese (5th – 3rd centuries BCE) and related changes which took place in Early Middle Chinese (2nd century BCE – 2nd century CE). Particular focus will be given to basic word order, object movement (e.g. topicalization, focus movement, fronting in negated clauses), and the structures of various types of embedded clause (e.g. relative clauses and complement clauses). Other topics, e.g. embedded and matrix yes/no questions, reflexive pronouns, passive constructions, noun phrase structure, verb phrase structure may be included as time permits. Students taking this course for credit will submit a short squib (approximately 3-6 pages) on a topic concerning Archaic or Middle Chinese syntax.

Level and requirements/prerequisites

A basic knowledge of Classical Chinese, as well as Minimalist syntax, would be helpful but is not required.

Reading to be done beforehand

- Aldridge, Edith. 2013. Survey of Chinese Historical Syntax Part I: Pre-Archaic and Archaic Chinese. Language and Linguistics Compass 7.1: 39-57.

- Aldridge, Edith. 2013. Survey of Chinese Historical Syntax Part II: Middle Chinese. Language and Linguistics Compass 7.1: 58-77.

Background readings

- Dong, Xiufang. 2002. Gu Hanyu Zhong de ‘zi’ he ‘ji’ [‘Zi’ and ‘ji’ in Classical Chinese]. Gu Hanyu Yanjiu 54.1: 69-75.

- Feng, Shengli. 1996. Prosodically constrained syntactic changes in early archaic Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 5: 323-371.

- Gallego, Angel J. 2014. Deriving featuring inheritance from the copy theory of movement. The Linguistic Review 31.1: 41-71.

- Mei Guang. 2015. Shanggu Hanyu Yufa Gangyao [Essentials of Archaic Chinese grammar]. Taipei: Sanmin Book Co.

- Meisterernst, Barbara. 2010. Object preposing in Classical and Pre-Medieval Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 19: 75-102.

- Yang, Mengmeng. 2019. “Zhu zhi wei” jiegou de jufa [The syntax of the NP-ZHI-VP construction in Old Chinese]. Zhongguo Yuwen 390.3: 278-295.

Slot 2

Lecturers: Nicholas Kontovas

This course is intended as an overview of the grammar of the Modern Uyghur languages. In addition to the contemporary grammar of the language, the origins of grammatical forms and the overall history of the language from both genetic and areal perspectives will also be covered. By the end of the course, students who successfully complete the pre-readings before each class will also gain the ability to read texts in Uyghur with the use of a dictionary and reference grammar.

Grading Policy

In accordance with Summer School Policy, students requiring credit for this course should inform the instructor ASAP so that they can prepare an adequate assessment tool. This can take the form of a squib (short exploratory research paper), a short translation, or a one page sit-down exam to be completed after the last day of class.

Course Prerequisites

Students without prior knowledge of the Arabic script are strongly encouraged to read and complete the small packet introducing the fundamentals of the Uyghur Erep Yéziqi (Uyghur Arabic Alphabet) before the first day of class if they intend to complete the reading portion of the course.

Weekly Schedule

Week 1

| Day 1 | historical overview; phonology; transcription; writing systems |

| Day 2 | vowel reduction & raising; vowel length; non-verbal predicates; pronouns |

| Day 3 | nominal inflection; plural marking; existence & possession; loanwords |

| Day 4 | ‘primary’ tense/aspect/mood/evidentiality marking; infinitives; verbal negation |

| Day 5 | ‘secondary’ tense/aspect/mood/evidentiality marking; lexical aspect; reading |

Week 2

| Day 1 | verbal nouns; verbal adjectives; reading |

| Day 2 | verbal adverbs; vector verbs; reading |

| Day 3 | newly grammaticalized forms; dialectology; types of evidentiality; reading |

| Day 4 | discourse particles; important Uyghur authors and poets; reading |

| Day 5 | review; reading |

Slot 3

Lecturers: Jeroen Wiedenhof

This course explores milestones and recurrent themes in the study of Chinese scripts through the lens of linguistics, and with an eye on their import for linguistics. We cover developments in the Chinese character script, review its influence on other writing systems, and study the impact of printing and digital revolutions. We will also investigate alternative written modes in the sinophone world, including Chinese calligraphy, ludic writing, alphabetical orthographies and linguistic systems of transcription.

Course objectives

Students will gain hands-on knowledge in a broad spectrum of linguistic disciplines, script studies, and language education; expand their technical vocabulary in Chinese and in English; analyze academic arguments; compare different positions and traditions with original observations; and present oral and written arguments in English.

Mode of instruction

On-campus course (no online or hybrid options) in the form of daily text readings, assignments, group discussions, and topicalized lectures. The language of instruction & discussion is English. An excursion has been planned for (at least) one session. In preparing texts, students will be expected to pool resources depending on individual backgrounds and reading skills in English and in Chinese (traditional & simplified characters and/or handwriting).

Materials

We will read texts in English and Chinese. These selections will be distributed through the Summer School. Daily assignments and other details will be available at the course’s website.

Requirements

Before coming to this course, please make sure to have read "The Chinese script" = Chapter 12 of Jeroen Wiedenhof, A grammar of Mandarin, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2015.

Slot 4

Lecturers: Rint Sybesma

In this course we revisit questions related to tense, tenselessness and finiteness. We start out from investigating these questions from the perspective of Chinese, more particularly, modern Mandarin, perspective, but conclusions we draw will have repercussions for general theorizing and, consequently, for other languages.

Level and requirements/prerequisites:

Basic knowledge of generative/minimalist syntactic theories is required. Knowledge of Chinese will be helpful, but is not a requirement.

Readings to be done beforehand:

Any introductory text book on minimalist/generative syntax

Background readings/readings to be referred to and/or discussed in class:

- Cheng, Hang (2021). All structures great and small. On copular sentences with shì in Mandarin. Doctoral dissertation, Leiden University.

- Grano, Thomas (2012). Mandarin hen and Universal Markedness in gradable adjectives, Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 30, 513–565.

- Husband, E. Matthew (2012). On the compositional nature of states. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Kratzer, Angelika (1995). Stage-level and individual-level predicates, Gregory N. Carlson and Francis Jeffry Pelletier (eds.), The generic book. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 125-175.

- Lin, Jo-Wang (2006). Time in a language without tense: the case of Chinese. Journal of Semantics 23(1), 1–53.

- Matthewson, Lisa (2002). An underspecified Tense in St’át’imcets. Paper presented at WECOL 2002.

- Musan, Renate (1997). Tense, predicates, and lifetime effects. Natural Language Semantics 5:271–301.

- Sun, Hongyuan (2014). Temporal Construals of bare predicates in Mandarin Chinese. Doctoral dissertation, Universities of Leiden and Nantes.

- Sybesma, Rint (2017). Finiteness. Encyclopedia of Chinese Language and Linguistics, ed. Rint Sybesma, Wolfgang Behr, Yueguo Gu, Zev Handel, C.-T. James Huang & James Myers, Leiden: Brill, Vol II, 233-240.

- Sybesma, Rint (2017). Tense. Encyclopedia of Chinese Language and Linguistics, ed. Rint Sybesma, Wolfgang Behr, Yueguo Gu, Zev Handel, C.-T. James Huang & James Myers, Leiden: Brill, Vol IV, 282-290.

- Sybesma, Rint (2019). “Xiàndìngxìng hé Hanyǔ zhǔjù (Finiteness and main clauses in Mandarin).” International Journal of Chinese Linguistics 6/2, 325-344. DOI: 10.1075/ijchl.19002.syb.

- Tsai, Wei-tien Dylan (2008). Tense anchoring in Chinese. Lingua, 118, 675-686.

Descriptive Linguistics

Slot 1

Lecturer: Martin Kohlberger

This course will explore language contact phenomena with special emphasis on cases where language contact occurs as a result of widespread bi- or multilingualism within a society. Examples will primarily be drawn from Indigenous languages of North America, although the course will aim to make generalizations that are applicable across the globe. The course will be tailored in particular to students who expect to undertake descriptive and documentary linguistic research, but can also be taken by any student with a basic linguistic background.

In the first part of the course, we will look at case studies from different multilingual societies to examine the kinds of grammatical and structural changes that languages undergo in different scenarios. We will distinguish between the borrowing of linguistic forms (matter borrowing) and the borrowing of functional linguistic structures (pattern borrowing). We will also highlight the areas within grammar that have been identified as being prone to contact-induced change (for example, the widespread borrowing of classifiers, ideophones and markers of information structure).

In the second part of the course, we will focus on cases of particularly intensive language contact. We will discuss the kinds of social and cultural scenarios which are conducive to creating stable and long-term multilingualism. This will include cases of deeply established trade relationships as well as different kinds of exogamous marriage patterns. Then we will analyse the linguistic outcomes of such scenarios, including the creation of a Sprachbund/language area, such as the Pacific Northwest, or even the creation of a mixed language, such as Michif in the Prairies of North America.

Slot 2

Lecturer: Maarten Mous

The course discusses Registers of Respect, Youth languages, Secret languages, Initiation languages, Argot, Taboo, Ritual language and language of the supranatural. In short, all situations in which we try to control the language we speak, either for respect, fear, or for identity purposes. We look into aspects such as language games, phonological manipulation, properties of parallel lexicon, inventory of manipulations and their limits, control in linguistics, psychology, philosophy. speech community of special language, social and psychological aspects, consequences for language change.

Slot 3

Lecturer: Martin Kohlberger

This course will introduce students to one of the most linguistically diverse regions of the world. There are over 300 languages – representing over 70 genetic units – currently spoken in Amazonia. We will start by exploring each of the major language families, their geographic distribution as well as important grammatical characteristics that languages within those families are known for. Then we will look at phonological, morphological, syntactic and discursive structures that stand out typologically. Thirdly we will focus on historical change and grammaticalisation pathways that are common for the region. Finally, we will look at the dynamics of language contact and the profound effect that cross-cultural interaction and multilingualism has had on many languages of the area. By the end of this course, students will not only be familiar with a number of languages of Amazonia and their typological features but will also have an appreciation for the valuable contribution that the study of Amazonian languages has had on linguistic theory.

Slot 4

Lecturer: Christian Rapold

This course offers an introduction to the analysis of tone in human language in a variety of perspectives, including phonetics, phonology, typology of tone systems, diachrony of the phonetics and phonology of tone, and field methods for tone data collection. The course includes practical exercises in the perception and production of pitch. At the end of the course the participants will be able to start the analysis of tone in an undescribed language and to situate the results in current discussions in the study of tone.

Level

A basic knowledge of segmental phonetics and phonology, and of morphology and syntax is required. Prior acquaintance with a tone language is not required.

Requirements

There will be daily homework assignments.

Online participants need a basic microphone for the practical exercises; in view of the course interaction they are kindly requested to have their cameras on during class.

Texts

Course documents will be provided.

Language Documentation Program

Slot 1

Lecturer: Andrew Harvey

This course is designed for students who are familiar with linguistic field methods (i.e. have attended or are attending a linguistic field methods course (such as the course at this summer school), or who have already conducted documentary / descriptive work). In this course, students will move beyond the core of linguistic data collection methods to ask questions of linguistic fieldwork as a methodology. Students will 1) consider the holistic experience of linguistic fieldwork (e.g., deciding research foci, building community relationships, and using the collected data); 2) evaluate and discuss recent calls for change in how fieldwork is conducted (especially Indigenous and Black perspectives); and 3) examine real-world cases of linguistic fieldwork from around the world.

Slot 2

Lecturer: Christian Rapold

Fieldwork is the backbone of modern linguistics—often invisible but vital to the whole field. Whatever you do with your data following your theoretical persuasion and interests, the analysis stands and falls with the quality and type of data you use. This course offers a broad overview of theoretical and practical aspects of field methods. An important part of each session will be devoted to hands-on fieldwork practice with a speaker of a non-Indo-European language, developing skills that are rarely acquired through books or lectures.

Level

Familiarity with the IPA and basic knowledge of articulatory phonetics, phonology and morphology is required. Basic knowledge of syntax would be an advantage but is not necessary.

Requirements

There are daily homework assignments (20-30 min. each day, one time 60 min.) The course can only be attended in person as we work with a speaker who is present onsite.

Texts

Bowern, Claire (2015). Linguistic fieldwork: A practical guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Further course documents will be provided.

NB: The number of participants of this course is limited, so that a quick registration is advisable.

Slot 3

Lecturer: Andrew Harvey

This course introduces students to two pieces of software that are widely used in language documentation, offers hands-on training in each software application, and then goes further to demonstrate how to use the two of them together. The course follows a typical fieldwork workflow, starting with audio segmentation, transcription, and translation in ELAN using EAF templates. Students learn how to compile their data into a searchable corpus and how to conduct searches across their data. The course will then shift to FLEx, providing students with basic knowledge of its primary functions and how to build a lexicon, work with texts, and parse and gloss data. Finally, students will be guided through a step-by- step ELAN-FLEx-ELAN workflow so that they have the ability to benefit from the advantages offered by each program.

1. Introduction to ELAN, the primary modes

2. Using templates, starting a project, segmentation, transcription, translation

3. Creating an ELAN corpus, searches with regular expressions

4. Introduction to FLEx, the primary modes

5. Lexicography with FLEx, working with texts, parsing and glossing

6. ELAN-FLEx-ELAN workflow

Slot 4

Lecturer: Lea Zuyderhoudt

In this course listening is the starting point for learning about research and oral traditions. The course combines theories and methods for researching oral texts with a practical and skills-based approach. Not only do we look into how choices with regards to researching and recording can be based on listening to that what people share in a collaborative approach. We also learn by practical assignments with storytellers that contribute to the course. This course invites students to develop skills as well as rethink what is known about research methods, orality and the stories and languages people share within different fields of research. We work with both ancient and highly contemporary texts to give you practical skills and hands on research experience and will help you to reflect on the dynamics of these traditions in new ways. The course research practices for oral traditions benefits those interested in languages/linguistics, ethnography/anthropology, journalism, history as well as those who are interested in orality and storytelling itself.

In this course students will:

1. Acquire critical knowledge of theories and methods of analysis of oral performances;

2. Acquire and practice techniques of both recording text and transcription and translation;

3. Acquire and practice techniques of ‘visual’ description of performances and their context;

4. Situate an oral performance within its cultural and socio-historical context.

Workshop “Using video for documentation”

The course can be combined with attending the extra workshop “Using video for documentation”. Details will be announced later.

Indo-European program I

Slot 1

Lecturer: Marieke Meelen

This course will focus on synchronic linguistic features of the Middle Welsh language (11-15th centuries). Students will be introduced to Celtic languages in general and their place among other Indo-European languages. The classes will contain a mixture of learning Middle Welsh grammar whilst translating the oldest Arthurian tale Culhwch and Olwen and analyzing secondary literature concerning different tools and methods in the field of Celtic linguistics and philology.

After this module students will be able to

- put Welsh in the context of other Celtic and Indo-European languages;

- translate excerpts of an unseen Middle Welsh text;

- explain grammatical constructions in a straightforward way.

Slot 2

Lecturer: Rolf Bremmer

The course offers an introduction to the Old Frisian language. We focus on reading and appreciating Old Frisian texts, especially the law texts which make up the bulk of the corpus of Old Frisian and which can be very vivid. Old Frisian grammar and structure will be discussed, including such problems as dialectology, periodization and its place within Germanic, including the Anglo-Frisian complex. We also pay attention to how Old Frisian literature functioned within the feuding society that Frisia was until the close of the Middle Ages.

Requirements

The daily homework consists of small portions of text to be translated, some grammatical and other assignments on the text, and reading a number of background articles.

Text

Rolf H. Bremmer Jr, An Introduction to Old Frisian. History, Grammar, Reader, Glossary (Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2009; revised reprint 2011).

Students can order the Introduction with a rebate of 50% straight from the publisher. Send your order to bookorder@benjamins.nl with your full postal address and the words 'Summer School'. As soon as you have paid the bill, the book will be sent to you.

Slot 3

Historical grammar of Sanskrit: see Indology program

Historical linguistics: see Linguistic Introductions

Slot 4

Lecturer: Alwin Kloekhorst

Hittite holds a special position in the field of Indo-European linguistics. It is the earliest attested language of this family, with texts dating back to the 18th c. BCE. Moreover, and more importantly, is it the best known member of the Anatolian branch, which is nowadays generally regarded as the first branch that split off from the Indo-European family tree (the “Indo-Anatolian” model). The many archaic features of Hittite are therefore of paramount importance for the reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European and the prehistory of the Indo-European family as a whole.

In this course, we will extensively treat the linguistic analysis of Hittite from a synchronic and historical point of view. We will discuss its affiliation to other Anatolian languages (especially Cuneiform Luwian, Hieroglyphic Luwian, and Lycian), the reconstruction of a Proto-Anatolian mother language, focusing on the features that are of importance for reconstructing Proto-Indo-European.

Some of the sub-topics that will be treated are:

- the Indo-Anatolian hypothesis

- the outcomes of the laryngeals in Anatolian and in Hittite

- the phonological interpretation of the cuneiform script

- the role of Hittite in reconstructing PIE nominal ablaut-accent classes

- the origin of the Hittite hi-conjugation

- etc.

Requirements

In order to follow this course it is recommended to have at least some knowledge of synchronic Hittite, but this is not obligatory.

Indo-European program II

Slot 1

Lecturer: Tijmen Pronk

The prosodic systems of Baltic and Slavic languages play a crucial role in the historical phonology of these languages. In this course, we will discuss the origins of tone, stress patterns and stress shifts, and the relative chronology of prosodic changes in Baltic and Slavic. The focus will be on the historical interpretation of the accentual system of those East Baltic and South Slavic languages that have a restricted tone system, but we will also discuss the history of, e.g., Russian stress patterns and Czech and Slovak vowel length distinctions. In addition, we will reflect on the Indo-European origins of the Baltic and Slavic accentual systems and on the role these systems play in the reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European.

Requirements

Participants are expected to have basic knowledge of the historical phonology of Baltic and/or Slavic languages. This can be obtained before the beginning of the course by studying the relevant chapters of Pietro U. Dini’s Foundations of Baltic Languages and Alexander M. Schenker’s The Dawn of Slavic, both available online at archive.org.

Slot 2

Lecturer: Velizar Sadovski

We shall discuss a number of sacred texts and ritual practices as transmitted by well-known pre-classical and classical Greek and Latin literature together with (well- or) very-much-less-known representatives of (oral and written) ritual and hymnal poetry of other ancient Indo-European traditions such as the ones of the Old Indian ritual poetry and prose from the Rig-, Atharva- and Yajur-Veda, Gāthic and Young Avestan hymns and liturgies, Old Norse Eddas and Old Icelandic sagas, the Cattle Raid cycle of Celtic epics but also Old Irish Triadic hymns and St. Patric’s Breastplate Poem, Balto-Slavic incantations and tales, Albanian riddles, Armenian lyro-epic songs of the Birth of the Hero, Anatolian King’s Lists and sacred laws – highly intriguing disiecta membra of a large Indo-European mythopoetic and ritual database but also of heroic narratives with heuristic significance for the cultural reconstruction, which have often escaped the attention of (Classical) philologists of present day.

The main focus of this historical-comparative course lays on lexical, phraseological, textual, and especially hyper-textual levels of Indo-European languages, analyzing oral and written text corpora used in individual Indo-European religious, ritual and narrative-mythological traditions and the possibility of reconstruction of formulae and contexts of common relevance and with theological, cosmological and anthropological significance.

Our class will thus concentrate on the linguistic representation of fundamental Indo-European mythological and religious concepts to be reconstructed for the PIE lexicon on the basis of ancient texts of oral poetry and in the respective literary collections both of hieratic text sorts and of genres of popular poetry and folklore, of “Götterdichtung” and “Heldendichtung”. Based on the good traditions of the Leiden Summer classes on Indo-European sacred texts, the course in the framework of the 14th edition of the Leiden Summer School will offer a completely autonomous class adapted to the interests both of absolute newcomers and of more advanced colleagues, being open for proposals of themes and topics in addition to the main program.

(A) rituals and sacred words for communication with the Divine: formulae for addressing God in votive acts, oaths, and solemn promises; divinations and ritual prognostics; fire sacrifices, aparchai, offering of bloody and unbloody victims,

(B) rituals and related (aetiological) myths emulating cosmological acts: establishing of sacred space (temenoi, temples, augurial precincts), house construction divine and human, piling of the fire altar, of funeral pyres and tombs, hissing of pillars, signs and monuments for eternity

(C) rites of anthropological relevance: wedding rites, rituals for child conception, birth and growth rituals, naming rituals (name-giving, polyonymy, cryptonymy), initiations for key moments of life, spirutual initiation

(D) hymnal and heroic poetry and prose: cultic and narrative significance as sacred way of re-creation and reproduction of the Universe by words

Course outline

Our scope is to go beyond standard topoi and running gags in the history of research into “Indogermansiche Dichtersprache” and find what a fresh, 21st century viewpoint on traditional IE texts can contribute by actively employing achievements, results and methodological innovations IE linguistics arrived at, in the half century after Rüdiger Schmitt’s classical monograph on IE poetry and the decades after Calvert Watkins’ masterpiece of ‘draconoctony’, in which crucial contributions such as Martin L. West’s, Gregory Nágy’s, and Michael Janda’s monographs strongly revivified the interest in the intersection between ritual, myth and religion as reflected in the language of IE poetry.

After a short survey of classical studies on the subject in form of a concise “history of ideas” and together with a survey of relevant PIE social structures such as priesthood, sacred kingship and Männerbünde and their respective mythologies, we shall concentrate on various mythological, ritual and poetic forms of classification of the Universe and systematization of religious and practical knowledge about nature and human communities in their relationship with the Sacred:

(1) Creation myths and their reproduction in daily ritual acts: (a) cosmogonic myths and their reflection in rites such as setting of the sacrificial fire, fixing the pillar of a nomadic tent, sacrificing first bites of food and drops of drinks, libations of milk into the Fire etc., (b) foundation myths of towns, settlements and tribal groups (from Kadmos’s Thebes and the Roma quadrata of Romulus and Remus up to the “Aryan homeland” of the Avesta as well as the Five Tribes of India, the Five Clans of Ireland or the Four Stems of Mabinogi etc. (c) We shall develop the theme of the “sacred bestiary” in Indo-European cosmogonic and cosmological myths, in continuation of what first introduced in 2002, but completely independent from previous discussions and with new examples of myths of animals appropriate for newcomers (incl. animalistic representations of eponyms of towns, tribes and countries as well as theriophoric personal names of [cultural] heroes).

(2) Sacred Chrono-logy: of divine and human generations, esp. the motifs of “chthonic” vs. “uranic” deities: here, old dichotomies such as the ones of Asuras and Devas, of Titans and Olympic deities, of Vanir and Æsir, will be re-assessed also in terms of this dialectics between sedentary establishment and semi-nomadic, moving expansion of the community, including also:

(3) Sacred Genea-logy: (a) the narrative of the change of generations (from the Hittite versions of the Kumarbi myth via the Five Ages at Hesiod up to Celtic and Germanic evidence of generational sequences), (b) the catalogues of predecessors (and descendants) of a deity or of a hero as mythological form of characterization and glorification of an extraordinary (mythical or historical!) personality,

(4) Sacred Onomasio-logy, between the formation of appellatives designating sacred concepts and of prper names. Specifically onomastic themes concentrate on names, epithets and (poetical) phraseology and include name-giving with religious reference, theophoric names and ones with reference to sacred time-and-space, to astrological/astronomical events, to the divine patron of the day or month of birth, names in their significance as social or genealogical identifier (of the relationships of the individual in comparison to one or more lines of descent, referring to the [pro-]paternal lineage, to another name, for instance maternal, οr to various cognomina) but also in their “augural”, solemn, benedictory function;

(5) Sacred Topo-graphy – cosmological representations such as the ones on the Homeric and Hesiodic Shields (of Achilles, of Heracles) and their parallels in other Indo-European traditions (e.g. the protection catalogue on St. Patrick’s breastplate) – and Sacred Topo-logy: mythological depiction of space by linking heavenly and earthly directions (bidimensional [horizontal], tridimensional [vertical] and pluridimensional [mystic] ones) to deities, colours, plants and other natural phenomena or ethnic and social groups (as in the delineation of the sacred space in archaic Greek and Italic (Umbrian, Old Latin) cults, in the Vedic ritual of construction of the altar and even in the Deutsche Sagen of the Grimm brothers!),

(6) Sacred Bio-logy: festivals and rituals containing classification of the vegetal and animal world according to utilitarian but also to ritual, esp. mythologically relevant principles – the Sacred Plants of the Atharvaveda, the Healing Plants of the Germanic (Old High German, Anglo-Saxon, Old Icelandic etc.) and Balto-Slavic “herbal magic”, but also the plant cosmos in the “Works and Days”, in the “Georgics”, in the Avesta etc.

(7) Sacred Physio-logy: ritual enumeration of body parts (a) in magico-medical healing rituals (with Irish, Anglo-Saxon, (Eastern) Slavic, Greek and Indic evidence); (b) in cosmological hymns depicting cosmogonies from the body parts of a primordial giant (in the Vedas and the Edda); (c) in rituals of cursing competitors in love, in court or in race (Greek, Latin, Sanskrit, Avestan examples).

(8) Sacred Socio-logy: the gods of establishment (of semi-nomadic “small-cattle breeders” or semi-sedentary farmers, with their chieftains and tribal organization) vs. the gods of para- and even antisocial groups. Special sub-theme: rituals of dangerous age-groups such as the Hellenic ephebes, Italic, Germanic, Welsh/Irish, or Indo-Iranian (teenage) boy gangs – myths of ‘centaurs and amazons’, totemic and animalistic cults, deemed transformation to beasts or yonderworld beings, the Wild Host etc.

(9) Sacred Numero-logy: ritual enumeration of entities (a) as fix closed numbers of elements, as in the “catalogues of (the four, six etc.) Seasons linked to other entities of the Universe (in the Veda; in the Irish Féilire of St. Adamnan of Iona etc.); as sacred triads, tetrads, pentads in multi-partite lists (Germanic, Celtic, Indo-Iranian), or (c) of regular sequences of entities, in increasing or decreasing patterns, all over the “Indo-Germania”.

(10) Sacred Areto-logy: (a) lists of Res Gestae of a deity or a hero as mythological and axiological patterns of history of creation, community, ethnicity, dynasty etc., from mythological catalogues (Herakles, Theseus) up to historical accounts of royal self-presentation (Darius the Great, Augustus etc.); (b) poetry of Peace and War: common IE collocations, lists of epithets, kenningar and names characterizing the person and deeds of a hero.

(11) Sacred Axio-logy: (a) aspects of the themes of the primordial Rightness (and its antagonist, the Wrongness) as regulator of the world’s Order, Harmony and Truth (and of the Priesthood and Sacred Kingship as guarantee of divine order on the earth); (b) the legal force of the spoken word: oaths, prayers and other uerba concepta in their significance for the comparative study of ritual speech acts as predecessors of a religious and social law system; (c) culture of Memory (theogony, cosmogony, anthropogony) between Old Irish filid and bards and Old Indo-Iranian kavi-s as Kings-Poets of divine and social Order-and-Truth.

(12) Sacred Leiturgo-logy, I: “Scari-fying Sacri-fices” – rites and poetic narratives concerning animal and human offerings for appeasing chthonic, teratomorphic and uranic deities: (a) chthonic topoi such as the one of the “severed head” from the utmost eastern Indic Yajur-Veda up to the Celts in Southern Gaul (as described by Poseidonios) and Ireland; (b) poetics of funeral rituals – like in the burial of Scyld (Beowulf 26ff.) and Beowulf’s vision of his own funerals (2799ff.) as compared with other Indo-European depictions of such liminal rites (e.g. the burial of Patroklos in the Iliad, the Vedic funeral mantras etc.) – and of the hope of resurrection; (c) teratological motifs concerning abstract forces, numina and non-personified powers influencing the daily life of humans.

(13) Sacred Leiturgo-logy, II: Theo-xenia, or rituals of hosting, esp. nourishing with ritually prepared and cooked food in festivals and everyday rites: starting with the paradigms established by Malamoud (“Cooking the world”) and by the group around Marcel Detienne and Jean-Pierre Vernant (“The cuisine of sacrifice among the Greeks”), and continuing with a series of new materials from the last three decades concerning local Greek, Roman, Baltic, Indo-Iranian and Germanic cultic practices of “theoxeny”.

(14) Sacred Poeto-logy: (a) Linguistic and stylistic forms and genres of ancient Indo-European poetry – hymn, mantra, prayer, ritual complaint, ritual conjuration, oath, cursing and blessing etc. (b) formal-stylistic figures on various language levels, especially techniques of formulation, syntax and stylistics of complex sentence structures; (c) methods of composition and their linguistic representation in specific forms: cyclic compositions, catalogues and lists, dialogic hymns etc.; (d) names and phraseology in the mirror of religion, ritual, culture, society.

We shall illustrate the respective analysis with Vedic mantras and Avestan hymns, chapters of Homer and Hesiod, Greek incantations in metrical inscriptions and their literary pendants (like Attic tragedy), Old Latin ritual carmina (in their relation with the fasti), calendar-related formulae and 'uerba concepta' for legal purposes, Hittite prayers, oaths and purification hymns, inherited topoi of Balto-Slavic "Heldendichtung", Germanic spells for cursing and blessing, healing charms in Celtic.

Focus

Exploration of Language of Indo-European Poetry represents an object of continuous interest of comparative linguistics ever since 1853: after Adalbert Kuhn discovered a phraseological parallel between Homeric Greek and Vedic – the classical heroic notion of ‘imperishable glory’ –, the domain of linguistic comparison extended itself not only over phonological or morphological correspondences but also over higher language levels: syntax and stylistics, incl. poetical formulae, figures of speech, epithets and proper names. The main requirement has been to collect such formulae, epithets or names that show consequent correspondences both on the level of semantics and (especially) in their phonologic shape as well as on the level of precise patterns of word-formation and (underlying) syntactic structures.

After the comparative interest in "Dichtersprache" have reached a peak in the decade after the World War I (with authors such as É. Benveniste, H. Oldenberg, H. Günthert, G. Dumézil, P. Thieme), it needed half a century until research tradition between 1850es and 1950es has been presented in a systematic way, in Rüdiger Schmitt’s "Dichtung and Dichtersprache in indogermanischer Zeit", the classical study of this particular discipline of Indo-European Studies for other forty years. The well-known monographs by C. Watkins, G. Nágy, V. N. Toporov, J. Puhvel, M. L. West, W. Burkert, and Michael Janda, are a material expression of intensification of scholarly debate on Language of Poetry in the last 45 years, most recent contributions to which also include compendia and encyclopaedic projects by J.-L García-Ramón, N. Oettinger and P. Jackson, D. Calin and others. A new comprehensive presentation of the topics of this debate in a special volume of the "Indogermanische Grammatik" (Heidelberg) on Indo-European Stylistics and Language of Poetry is in planning:

The present class aims at presenting a part of the material to be included in this compendium, in form of a conspectus of themes and questions illustrated by some "praeclara rara" that intend to focus the attention of participants on the current development of studies and methods – but also on new themes that arose only in the last few decades.

Presentations and discussion

As we always underline, the Leiden summers are intended to provide the possibilities of highly intense but largely horizontal contact between students and teachers on the same eye-level, in the open and relaxed atmosphere of South Holland, of the cafés, pancake houses and beer gardens at the Rhine. Our discussions often continue long after the daily classes and the evening lectures, thus stimulating future professionals and present colleagues from different countries to become acquainted with each other's work and personalities. Therefore we shall read a series of smaller or bigger portions of various Indo-European texts accompanied by relevant translations and thus available to for students still not acquainted with the languages concerned. Beside the classical lecture form, we shall aim at reaching a certain level of interactivity in class, including place for questions of special interests of participants concerning their theses or papers in preparation, as well as excursive surveys of special problems in form of short papers: a few of the students may be encouraged to give short presentations (ca. 20 min.) on topics of their special interest and/or on more general themes relevant for the class.

Slot 3

See Iranian program

Slot 4

Reading Runic inscriptions

Lecturer: Arend Quak

The course will give an introduction in reading runic inscriptions from the 2nd to the 17th century AD. First a survey will be given of the possible origins of the runic script. Then the signs and the problems with transliteration and transcription will be discussed. Inscriptions in the older Futhark will be treated with the help of pictures and drawings. Even examples from the smaller corpuses of the Old English and Old Frisian runic inscriptions will be reviewed. In the second week the runic inscriptions in the Younger Futhark (from the Viking Period and the Middle Ages in Scandinavia) will be shown and interpreted in pictures and drawings. The aim of the course is to provide a basic knowledge in reading and interpreting these inscriptions. For this course some basic knowledge of (one of) the Old Germanic languages is recommended.

Tocharian A language and literature: see Central-Asiatic program

Italo-Celtic program

Slot 1

Lecturer: Michael Weiss

In this course we will survey the remains of the Sabellic languages, Oscan, Umbrian, South Picene, and the minor dialects. We will pay particular attention to the ways in which Sabellic contributes to the reconstruction of Proto-Italic, to the interrelationships between the Sabellic languages, and to areal phenomenon shared across the ancient languages of Italy.

Level

Basic knowledge of Latin required.

Reading (not compulsory)

Rex E. Wallace, Sabellian, in: Roger D. Woodard (ed.). 2004. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages, Cambridge, 812-839.

Slot 2

Lecturer: Michael Weiss

In this course we will review the scanty remains of the other Indo-European languages native to Ancient Italy, Venetic, Messapic, and Sicel. We will discuss the phylogenetic position of these languages and the larger question of the position of Italic within the PIE family. Our focus will be mainly linguistic but we will also discuss archaeological and palaeogenetic evidence.

Level

Basic knowledge of Latin required.

Reading

- M. Weiss, Italic, in: Th. Olander (ed.). 2022. The Indo-European language family: A phylogenetic perspective. Cambridge. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/indoeuropean-language-family/italic/473A395FABB6E9FB91AE75076F390D29

- M. Weiss, Italo-Celtic, in: Th. Olander (ed.). 2022. The Indo-European language family: A phylogenetic perspective. Cambridge. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/indoeuropean-language-family/italoceltic/B4955FB7B7A6803DDD727795EA88C065

Slot 3

Lecturer: David Stifter

This course is meant as a beginners’ introduction to the Ancient Celtic languages spanning more than a millennium from the early 6th century b.c. until the middle of the 1st millennium a.d. The written traditions that will be covered are Cisalpine Celtic (i.e. Lepontic and Cisalpine Gaulish), Celtiberian, Gaulish, fragments from other regions on the Continent, and the insular Ogam corpus (i.e. Primitive Irish). The course will give an overview of what we know about these diverse traditions, plus an outline of their grammar, as far as it is accessible in the written documentation. The most important textual witnesses and other representative sources of these language will be introduced and discussed.

First readings

- David Stifter, Cisalpine Celtic. Language. Writing. Epigraphy [= AELAW Booklet 8], Zaragoza: Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza 2020.

- Francisco Beltrán Lloris and Carlos Jordán Cólera, Celtiberian. Language. Writing. Epigraphy [= AELAW Booklet 1], Zaragoza: Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza 2016.

- Alex Mullen and Coline Ruiz Darasse, Gaulish. Language. Writing. Epigraphy [= AELAW Booklet 6], Zaragoza: Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza 2018.

- David Stifter, Ogam. Language. Writing. Epigraphy [= AELAW Booklet 10], Zaragoza: Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza 2022.

Slot 4

Lecturer: David Stifter

This course is intended as a first introduction to the Old Irish language from a descriptive and comparative perspective, both for scholars with previous knowledge of the language and for beginners, especially coming from Indo-European Studies. Rudolf Thurneysen’s Grammar of Old Irish has been a corner stone for the study of the language since its publication in German in 1909, and esepcially since its moderately revised English translation in 1946. However, our understanding of the Old Irish language, the number of sources available to us and our understanding of them, the scholarly and technical tools, and the very way how we speak about language has undergone profound transformations since then. A lot of crucial progress has been made in historical phonology. In the morphology of Old Irish – nominal, pronominal and of course verbal – much more variation is recognised than was apparent at the beginning of the 20th century. Syntax and typology have assumed a much more prominent position in linguistic description. An attempt will be made to present the most important developments of the past years and decades in this course, which will covers aspects as diverse as the Indo-European background and the prehistory of Old Irish, the philology and comparative grammar of the language, soures and tools for its study, or the metrical analysis of its poetry.

Reading (not compulsory)

- David Stifter, ‘Early Irish’, in: Martin J. Ball and Nicole Müller (eds.), The Celtic Languages. 2nd Edition, Abingdon – New York: Routledge 2009, 55–116.

- Aaron Griffith and David Stifter, ‘Old Irish’, in: Saverio Dalpedri, Götz Keydana and Stavros Skopeteas (eds.), Glottothèque: Ancient Indo-European Grammars online (electronic resource). Göttingen: Universität Göttingen 2019. URL: https://spw.uni-goettingen.de/projects/aig/lng-sga.html.

Indology program

Slot 1

Lecturer: Carmen Spiers

In this hands-on, relatively fast-paced course, we will plunge into the vast world of Vedic Sanskrit literature (composed over a period covering approximately 1200 to 500 BCE) by following particular legends or themes through their evolution in texts spanning the entire Vedic period, while paying attention to how the language evolves with time and context. Besides the old and complex hymns of the R̥gveda, we have the simpler hymns and old prose of the Atharvavedic and Yajurvedic Saṁhitās, the later prose of the Brāhmaṇas and Āraṇyakas, and the terse instructions and occasional narrative digressions of the Sūtras; some legends even carry over into the Sanskrit epics (Mahābhārata and Rāmāyaṇa). Examples could include stories like that of “Dog’s-tail” Śunaḥśepa, a Brahmin purchased to replace a king’s son as victim in a sacrifice to Varuṇa; or of “From-a-dead-egg” Mārtāṇḍa, the aborted ancestor of humankind; stories around gambling and addiction; or lesser known legends such as that of god Indra’s transformation into the wife of “Bull-horse” Vr̥ṣaṇaśva and other metamorphoses. The texts we read will be supplied with vocabulary so that students can participate as actively as possible with minimal preparation. There are no formal prerequisites but a year or more of Sanskrit will allow one to make a stab at translation in class.

Recommended reference grammar

Macdonell’s A Vedic Grammar for Students (any edition; PDFs available online).

Slot 2

Lecturer: Niels Schoubben

When Aśoka, emperor of the Mauryan empire from ca. 268–232 BCE, decided to inscribe records of his military exploits and subsequent conversion to Buddhism in various Middle Indo-Aryan dialects (“Prakrits”), he unknowingly did a major service to Indological scholarship: his inscriptions formed the basis for the decipherment of the Kharoṣṭhī and Brāhmī scripts by James Prinsep in the 19th century; they remain an invaluable source for the military, social, and religious history of the Mauryan empire; and, last but not least, they are a treasure trove of data for comparative philologists interested in the linguistic landscape of ancient South Asia.

In this course, we will study the Aśokan inscriptions composed in an early form of Gāndhārī and written in Kharoṣṭhī, i.e. the 14 Major Rock Edicts from Shāhbāzgarhi and Mānsehrā (both located in present-day Pakistan). The course will consist of two parts: the first will introduce Middle Indo-Aryan, the Aśokan text corpus, the Kharoṣṭhī script, and the grammar of the inscriptions from Shāhbāzgarhi and Mānsehrā; the second part will be devoted to a close reading of these inscriptions. In doing so, we will pay special attention to the linguistic differences between the Shāhbāzgarhi and Mānsehrā versions while also examining which dialect features set Shāhbāzgarhi and Mānsehrā apart from the other versions of the same Rock Edicts (Girnar, Kalsi, etc.). Thus, the approach will be mainly linguistic, but care will be taken to ensure that students interested in the Aśokan inscriptions for different reasons also benefit from the course.

Level

Previous knowledge of Sanskrit is required. Any prior acquaintance with a Middle Indo-Aryan language (e.g. Pāli) would be helpful, but is not necessary.

Some background literature

- Baums, Stefan and Andrew Glass 2002–. Catalog of Gāndhārī Texts. Online available at https://gandhari.org/catalog. [Contains a digital edition of the inscriptions from Shāhbāzgarhi and Mānsehrā, including images and glosses].

- Bloch, Jules 1950. Les inscriptions d’Asoka: traduites et commentées. Paris: Les belles lettres. [Accessible edition with French translation and notes].

- Falk, Harry 2006. Aśokan Sites and Artefacts: A Source‐Book with Bibliography. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern. [Contains a comprehensive bibliography on all archaeological sites connected with Aśoka].

- Hultzsch, Eugen J. Th. 1925. Inscriptions of Asoka. Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol. I. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Standard but slightly outdated edition with English translation].

- Olivelle, Patrick 2024. Ashoka. Portrait of a Philosopher King. Yale: Yale University Press. [A new biography of Aśoka, partially based on the inscriptions].

- Schneider, Ulrich 1978. Die grossen Felsen-Edikte Aśokas: kritische Ausgabe, Übersetzung und Analyse der Texte. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Stemmatic edition of the Major Rock Edicts with German translation].

- Tieken, Herman 2023. The Aśoka Inscriptions: Analysing a Corpus. Delhi: Primus Books. [Contains a new translation of the whole corpus of inscriptions].

Slot 3

Lecturer: Alexander Lubotsky

In this course, which is geared towards both Indologists and Indo-Europeanists, we will analyze the historical development of Sanskrit grammar in order to understand why it is as it is. During the first week we will look at the major phonological developments (palatalization of the velars, Brugmann’s Law, Grassmann’s Law, various laryngeal reflexes, etc.), trying to establish the precise formulation of these laws and their chronological position. We will also look at the sandhi rules and the phonological ratio behind them. The second week will be dedicated to historical morphology (noun, pronoun, verb).

Level

At least one year of Sanskrit would be an advantage.

Slot 4

Lecturer: Velizar Sadovski

In the last decades, a series of authors engaged in serious scholarly research in the Indic society in comparative and historical perspective – within Ancient Indo-Iranian traditions as well as on a broader basis, in comparison with old Indo-European evidence. This involved, above all, an enlargement of the perspective that now concerns all social structures of Vedic and Epic India in the interaction between establishment – royal institutions, warrior elites – and para-establishment (age-)groups, the most important of which is, without doubt, the one of the male age set traditionally apostrophized as Old Indic “Männerbund”.

In this class, we are going to read and discuss a series of Vedic, Epic and Classical Sanskrit texts that function as our sources for Old Indic social structures from most ancient times to the classical period:

Course outline

I. With regard to the presentation of the sacred kingship as both socio-cultural institution and object of mytho-religious reflections, we shall systematically discuss:

1. Two hymns of the Rig Veda (R̥gveda-Saṃhitā), dedicated to Sacred Royalty and to the Leader of the Männerbund, respectively.

2.1.–2.2. The famous prose text Vrātya-Kāṇḍa of the Atharvaveda-Saṃhitā (Śaunaka version) in comparison with selected hymns of the Atharvaveda-Paippalāda 15 devoted to the protection of the Kingdom;

3. their Yajurvedic parallels:

3.1. from the Kāṭhakam and the Kapiṣṭhala-Kaṭha-Saṃhitā as well as

3.2. from the Maitrāyaṇīya- and the Taittirīya-Saṃhitā,

4.1.–4.2. together with selected portions of the corresponding Vedic prose, esp. exegetic chapters from the Brāhmaṇas of the Rigveda (Aitareya-Br.), the Black Yajurveda-Saṃhitās and Brāhmaṇas as well as the Śatapatha-Brāhmaṇa of the White Yajurveda,

5.1.–5.5. and, in the second major chapter (“The Fifth Veda”), a series of Mahābhārata texts related to the phenomena discussed.

II. Social establishment: social reality, ritual practices, mytho-religious patterns, cosmological transformations.

1. The above-mentioned part of the evidence will give us eloquent examples about how the figure and functions of the king within Old Indic society were depicted, on the one hand, in a pretty realistic way that largely corresponds to what we know about royal figures from other ancient Indo-European literatures.

2. On the other hand, the election and functioning of a sacred king was not simply conceived as a rational human social activity but perceived as a part of a mighty cosmo-poetic narrative linking elements of (sacral) macrocosm to items of (sacral[ized]) microcosm: The entire Universe was presented as object of influence of the election of the new king and its impact on the theological sphere (with catalogues of deities and their specific myths), on space (with lists of parts of the visible and invisible world and their respective populations), in time (the mythologized influence on the seasons and their respective fruits), rituals and cultic practices.

3. Beside Kingship itself, we shall concentrate on several institutions of the Old Indic state and strata of the dynamically changing Old Indic society, in order to show the specific differences in their presentation in canonical texts of the Brahmins and in the epic literature created by appointment of the royal courts concerned and underlining different, non-hieratic but dynastic, military and political dimensions of the image of the warriors and kings.

Focus

III. Männerbund: We shall discuss the sources concerning this phenomenon, the problems of methodology applied in earlier periods and at present, and the results of most investigations of the literary presentation of this social group as compared to newest archaeological sources.

The literary sources include material from several Vedic prose texts (such as the Śatarudriya in the version of the Vājasaneyi- and Taittirīya-Saṃhitā, the Pañcaviṁśa-, Śatapatha- and Gopatha-Brāhmaṇa, and ritual Sūtras [Lāṭy., Kauś.]), as well as – mainly – sociologically relevant Epic texts from the Mahābhārata and specialized Classical treatises.

The following short list of keywords will summarize a part of the characteristic features of (and history of research into) the Old Indic Männerbund which we shall discuss in class on the basis of the texts:

1. (Re)constructions of social systems in Ancient India compared to various Indo-European traditions:

● Unmarked social relations vs. special social structures (Sondergesellschaften). Fellowships of para-social and extra-social character: the Vrātyas.

● Implications for the possibility of reconstructing models of Indic social reality.

1.1. Renaissance of research interest ever since mid-1960es and esp. since 1990es:

● Key studies: e.g. R. Merkelbach (ephebic cults; Mithra societies), W. Burkert (Athenian and Spartan cults of Apollo with Indo-Iranian parallels), W. Bollée (Vedic basis of Modern Indian Männerbund), K. McCone (Indic and Celtic male gangs), H. Falk (brotherhoods and dice play), G. Meiser and R.-P. Das (Indo-European backgrounds of Indic and Indo-Iranian male societies), M. von Cieminski (Graeco-Roman parallels), M. Gerstein (Germanic parallels).

1.2. Precursor works (often: controversial) since 1902:

● Key studies: e.g. H. Schurtz (ancient ‘age groups’), O. Hoefler (‘shapeshifter myths and cults’); St. Wikander (Old Iranian Männerbund and OIran. Vaiiu / Ved. Vāyu cult).

1.3. Tripartite ideology theory and its varieties, modifications and controversies (G. Dumézil, M. Eliade).

1.4. Post-tripartite reconstruction systems (K. McCone).

By the comparison between the representation of (stative) social establishment and (dynamic) para-social groups, we shall aim at some generalizations and conclusions concerning the way Vedic and Epic Sanskrit literature reflects on its own society, both in a mytho-religous perspective and by means of descriptions in a field of tension between normativity and social self-reflection, whose more recent dimensions even contain elements of serious critical “sociological” analysis that gives us unique glimpses in a complex system of social reality.

2. Constructive elements of social reality of the Old Indic Männerbund (as compared with the social establishment):

2.1. Land possession, outsidership – par-oikia, met-oikia and ‘out-landishness’.

2.2. Vagabund groups expanding social nucleus on unconquered territories.

2.3. (Dis)continuing social space: between cultural expansion, ‘Great colonization’ and para-social, a-social or even anti-social nomadism.

2.4. Dynamic factor mobility – esp. wandering (vagabond) groups / Wandergruppen.

3. Constructive feature age – underage and age-of-minority groups: Age groups / Alters(klassen)genossenschaften.

4. Constructive feature gender – gender-marked and gender-segregative groups: Dynamic factor male gender – male communities / Männerbünde.

5. Constructive feature hierarchicity – para-governmental and out-of-government groups: Dynamic factor leadership: Youth packs constituted around a (young) male group leader. Group leader vs. ‘groupees’. Vrātya- both ‘member of a (vrātya-)grāma-’ and the leader, vrātya- vs. the group, grāma-.

6. Constructive feature cults and ritual, esp. official community cult – para- and extra-official cultic groups. Special and secret cult communities / Sonder- und Geheimkultgemeinschaften. Gods of the Männerbund.

7. Constructive feature (socio-religious) ritual initiation – para- and extra-initiatic groups: Dynamic factors sectaniarism/secrecy – esp. mystic and initiatic cults. Cults to totemic animals. Were-Wolves as metaphor of the pack.

8. Constructive feature communication – socio-constitutive linguistic acts: Ved. vratá- :: Avestan uruuata- ‘(verbal) indication, dictates, commandment, instruction’, then ‘(devotional) oath, vow’. Dynamic factors: commandment/obedience: Ved. vratá- as bidirectional linguistic regulative act, both ‘indication, commandment’ and as ‘vow (to obey toward the authority of such commandment)’ as different from ‘swearing of legally relevant oath’.

9. Constructive feature legality – para-legal and out-law groups:

10. Constructive feature family – para-familiar and extra-familiar groups: Para-matrimonial and extra-matrimonial communities – parasocial, esp. diastratic marriages; excommunicated companionships; non-married partners. Dynamic factor bachelorhood – bachelor fellowships / Junggesellenbünde.

11. Constructive feature socio-economic class – class/rank groups, economic establishment vs. outsiders.

12. Constructive feature ethnicity – ethnically marked or ethnically segregated communities. Dynamic factor Völkerwanderung – ethnic migration groups. Aryan migration waves: cf. A. Parpola, M. Witzel vs. H. Falk.

By the comparison between the representation of (stative) social establishment and (dynamic) para-social groups, we shall aim at some generalizations and conclusions concerning the way Vedic and Epic Sanskrit literature reflects on its own society, both in a mytho-religous perspective and by means of descriptions in a field of tension between normativity and social self-reflection, whose more recent dimensions even contain elements of serious critical “sociological” analysis that gives us unique glimpses in a complex system of social reality.

Participants and discussions

The class is intended a broader circle of students in the field of comparative and historical linguistics and philology, social anthropology, cultural studies, as well as, of course, Indic Studies. Knowledge of Sanskrit is a desirable prerequisite but no preliminary knowledge of Vedic Sanskrit is mandatory. We shall pay attention both to the historical context and to the linguistic form of the text to be discussed in intrinsic Indic perspective and from a comparative point of view. In the same way, without of course being a prerequisite, the class in “Vedic Poetry” (time-slot 1) can be a valuable parallel to our class.

The lecture is oriented to students of Historical and Comparative Linguistics (on beginners’, intermediate or advanced level), Indology, Indo-European studies as well as to colleagues from all philological disciplines interested in an introduction to the history of this archaic Indo-European language and culture in a wider religious and literary context.

A detailed Bibliography as well as reading materials on specific subjects will be distributed at the beginning and during the discussion of the respective topics and be supplemented by detailed handouts and PowerPoint presentations

Iranian program

Slot 1

Lecturer: Desmond Durkin-Meisterernst

Bactrian, attested for northern Afghanistan and southern Tajikistan from ca. the 1st to the 8th c. CE is the Middle Iranian language that has most recently become known to a degree that could not be expected even thirty years ago. This is primarily due to N. Sims-Williams' editions of the documents found in the 1980s in Afghanistan. Situated on the cross-roads between the Indian subcontinent and Central Asia its role in the Kushan empire (and later) and in the trade in goods and religions between many different cultures is becoming ever more evident.

The course will provide an introduction to the language in the context of Old Iranian and the other Middle Iranian languages and will present important texts such as the inscription of Rabatak and exemplary documents and some Buddhist texts in Greek script as well as the single Manichaean fragment in Manichaean script.

No previous knowledge will be assumed but familiarity with Greek script and with any Iranian language would be an advantage.

The course materials will be supplied.

Literature

- N. Sims-Williams: Indo-Iranian languages and peoples. Oxford 2002 (Proceedings of the British Academy 116).

- N. Sims-Williams: Bactrian Documents I, Oxford 2000, revised edition 2012, II, London 2007, III 2012. The second volume includes a grammar and a comprehensive glossary as well as editions.

Slot 2

Lecturer: Desmond Durkin-Meisterernst

Remarkably, Sogdian, the Middle Iranian language of Sogdiana in present-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, is much better attested outside of its original area than in it. The Kultobe inscription is the first text that we will read. Then the ‘Ancient Letters’, which were found not far from Dunhuang on the Chinese Wall. They are the first major source of Sogdian and we will read 1, 3 and 2 in that order. We will also look at some of the documents recently published by Bi Bo and Sims-Williams. Luckily there is one major exception to the rule that the sources are outside Sogdiana, and that is a find of 80 documents in the ruins of a small fortress, Mount Mug, on the Zerafshan river in present-day Tajikistan. These documents range from administrative tally-sticks and contracts to letters that passed between the last ruler of Panjikand and his spies and allies in the months before his attempt to flee invading Arab forces who caught him at this fortress in 722. The edition of this material was a great achievement of a group of Soviet Iranists in the 1960s. Livshits’ work was republished in English in 2015.

Following on an introduction to Sogdian and the Sogdian script, the course will aim to cover the main issues presented by the documents.

Course materials will be provided.

No previous knowledge of Sogdian will be assumed, though any knowledge of Sogdian or another Old, Middle or Modern Iranian language and of Sogdian script would be an advantage.

Literature

- Bi Bo and N. Sims-Williams: Sogdian Documents from Khotan in the Museum of Renmin University of China. 2018.

- É. de la Vaissière, Histoire des marchands sogdiens, Paris 2002 (Bibliothèque de l'institut des Hautes Études Chinoises vol. XXXII). = Sogdian traders. A history, Leiden, Boston 2005 (Handbook of Oriental Studies section 8. Central Asia, vol. 10).

- F. Grenet & É. de la Vaissière: The last days of Panjikent, Silk Road Art and Archaeology 8 (2002), 155-196.

- V.A. Livshits: Sogdian epigraphy of Central Asia and Semirech’e. Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, 2015.

- N. Sims-Williams: The „Ancient Letters“ and other Early Sogdian documents and inscriptions. Corpus inscriptionum Iranicarum 2023.

- É. Trombert, Les Sogdiens en Chine. Paris 2005, 181-193.