A new microscope for the quantum age: finally seeing how quantum materials behave

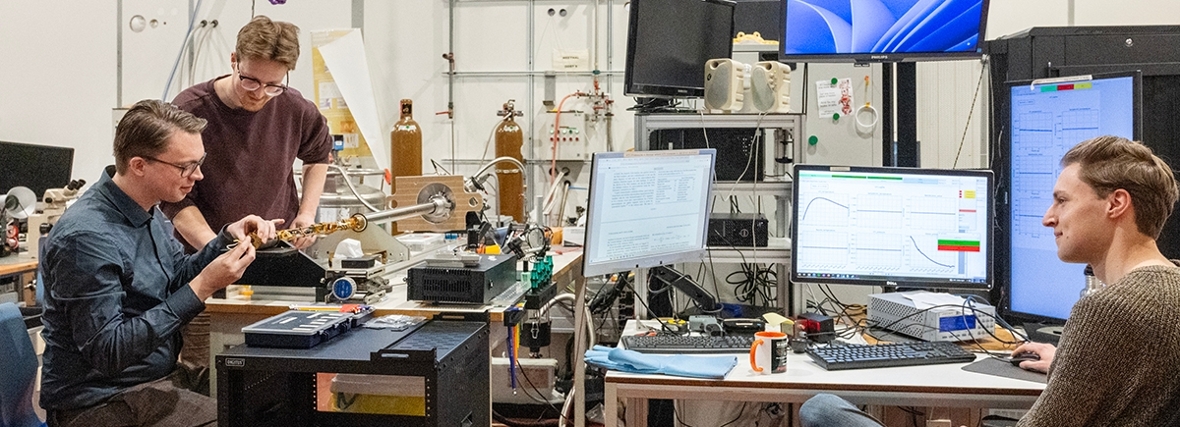

PHYSICS image: C. Huygelen

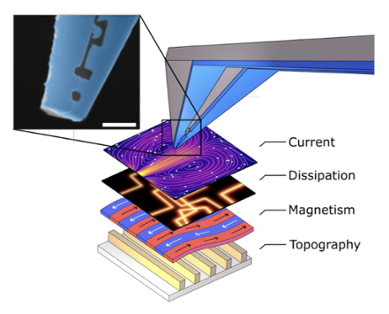

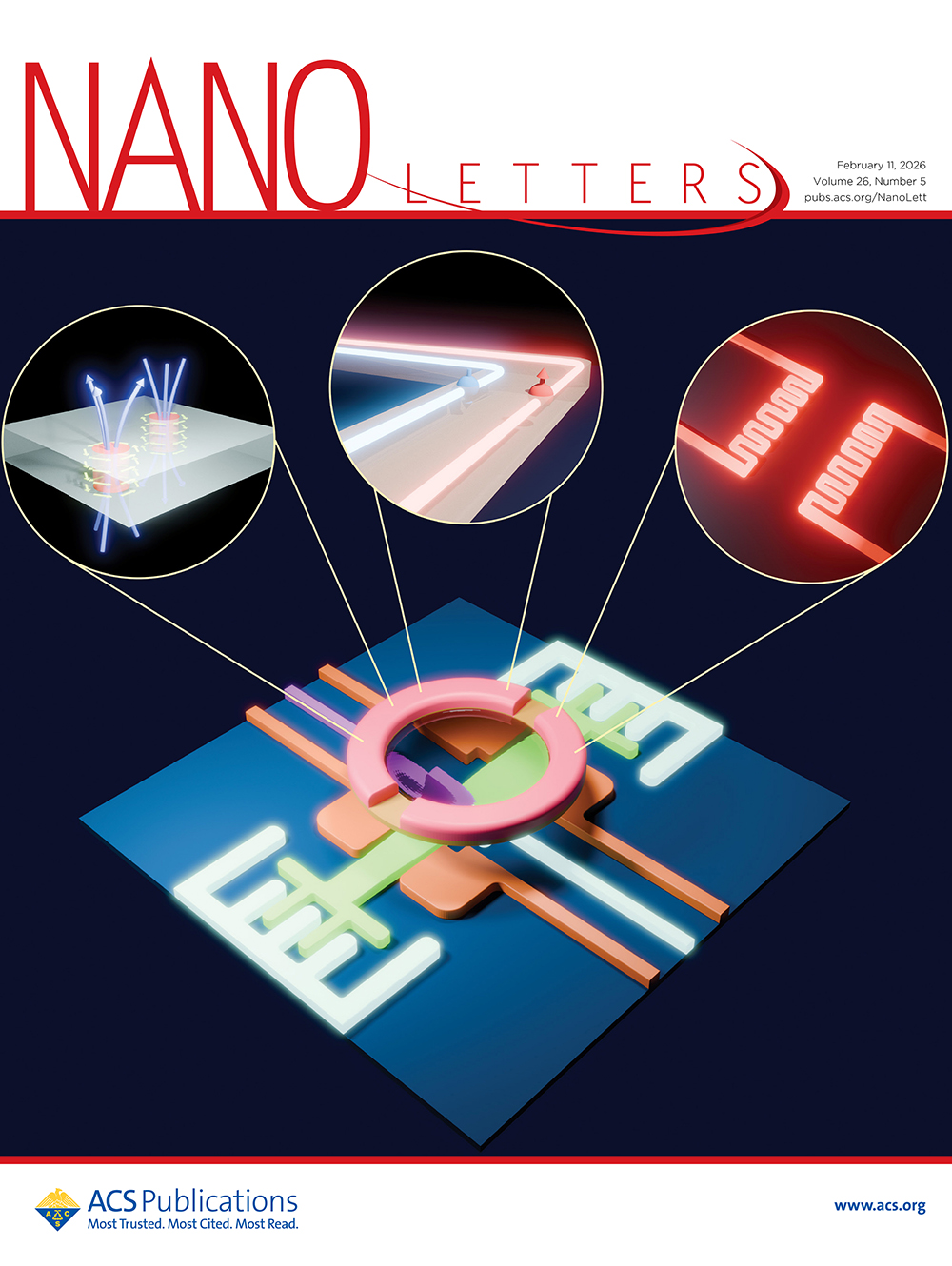

Physicists in Leiden have built a microscope that can measure no fewer than four key properties of a material in a single scan, all with nanoscale precision. The instrument can even examine complete quantum chips, accelerating research and innovation in the field of quantum materials.

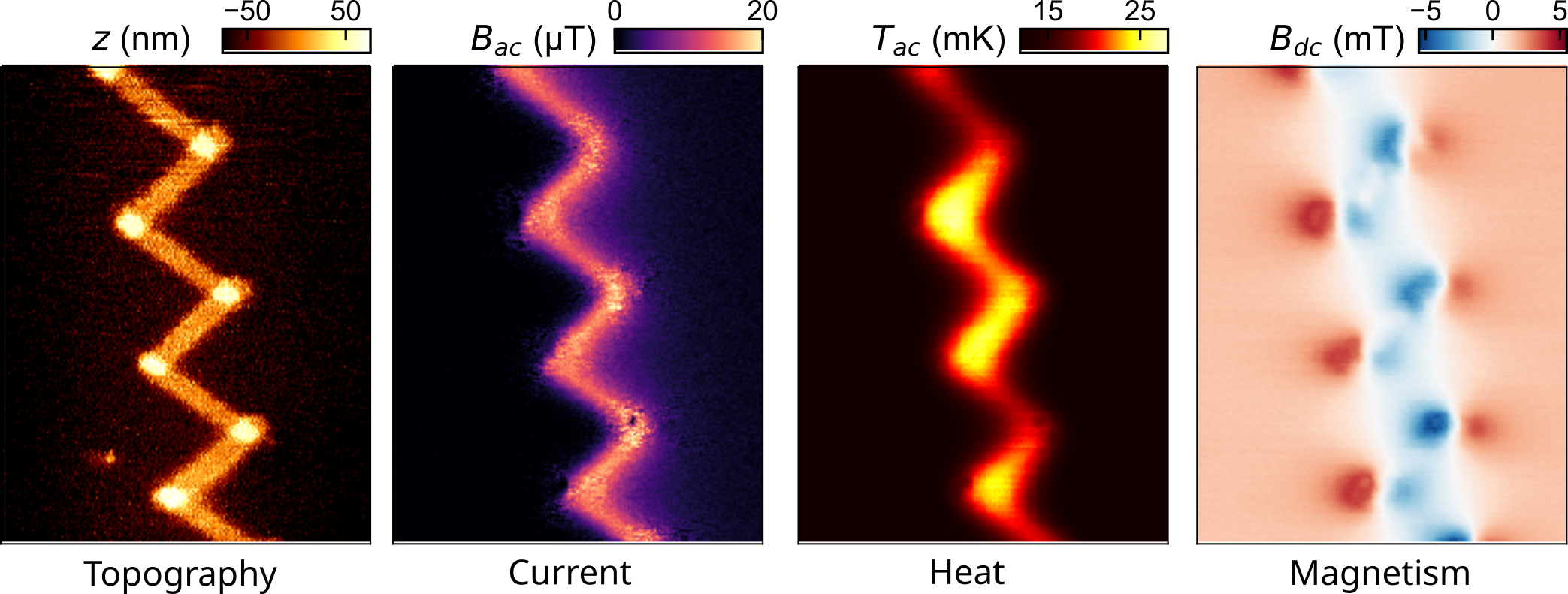

Temperature, magnetism, structure, and electrical properties. These are the material characteristics that this new microscope reveals. ‘It almost feels like having a superpower,’ says Matthijs Rog, a PhD student in Kaveh Lahabi’s research group. ‘You look at a sample and see not only its shape but also the electrical currents, heat, and magnetism within it.’

Kaveh Lahabi, who leads the group: ‘This microscope removes the experimental bottlenecks that have long limited the study of quantum materials. This is not an idealized technique – it works on the systems we actually want to understand. Furthermore, the sensitivity of our measurements tends to impress a lot of my physicist colleagues.’

Answering fundamental questions

Understanding the workings of quantum materials and devices (see box) is crucial for next-generation technologies such as quantum computing and sensing. Currently, it is still not fully understood how these materials function, because of their complexity: their magnetic, electronic, thermal and structural properties are all tightly intertwined on very small scales. Because this microscope can directly visualize these properties, it can be used to answer fundamental questions and learn how to effectively use quantum materials.

Quantum materials – what's that about?

Quantum materials are materials whose properties can only be properly understood using quantum mechanics. An example is a superconducting material, which can conduct electric current without resistance. Normally, quantum features can only be observed on the scale of individual atoms and a few nanometres, but quantum materials already behave quantum-mechanically on the millimetre scale. No one knows why, because they are so complex. The material contains billions of particles, all of which behave in a ‘quantum’ way. . ‘Such complexity is very hard to capture in a theory,’ Rog explains. ‘A lot of things come together at the smallest scales. It is therefore very nice that we can use this microscope to simply look for ourselves how these materials behave, and why they do what they do.’

‘Whatever quantum material we place under this microscope in the coming years, I’m certain we’ll discover something new,’ Rog predicts. Materials have never been studied in this way before. ‘Until a few months ago, our experiments were mainly about proving that the microscope worked. Now we can start tackling the real puzzles: materials we genuinely find interesting. We can’t wait.’

From flat crystals to uneven quantum chips

Rog explains: ‘Most existing microscopes only work well with very flat samples. That’s limiting, because many of the most interesting effects occur at the edges of materials or at the boundary between two different quantum materials. Our microscope has no trouble with that at all – it can examine a bumpy chip just as easily as a flat crystal.’

-

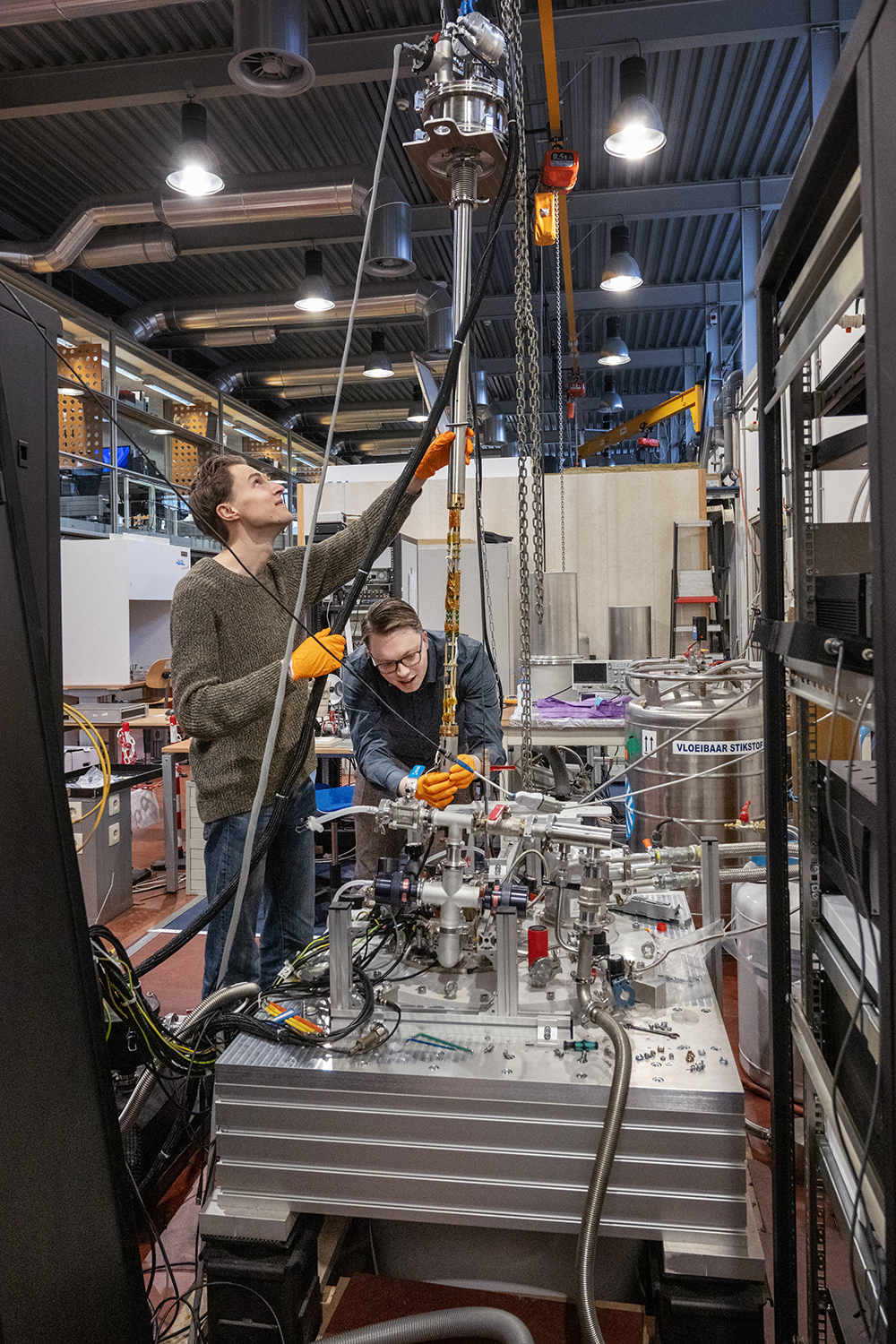

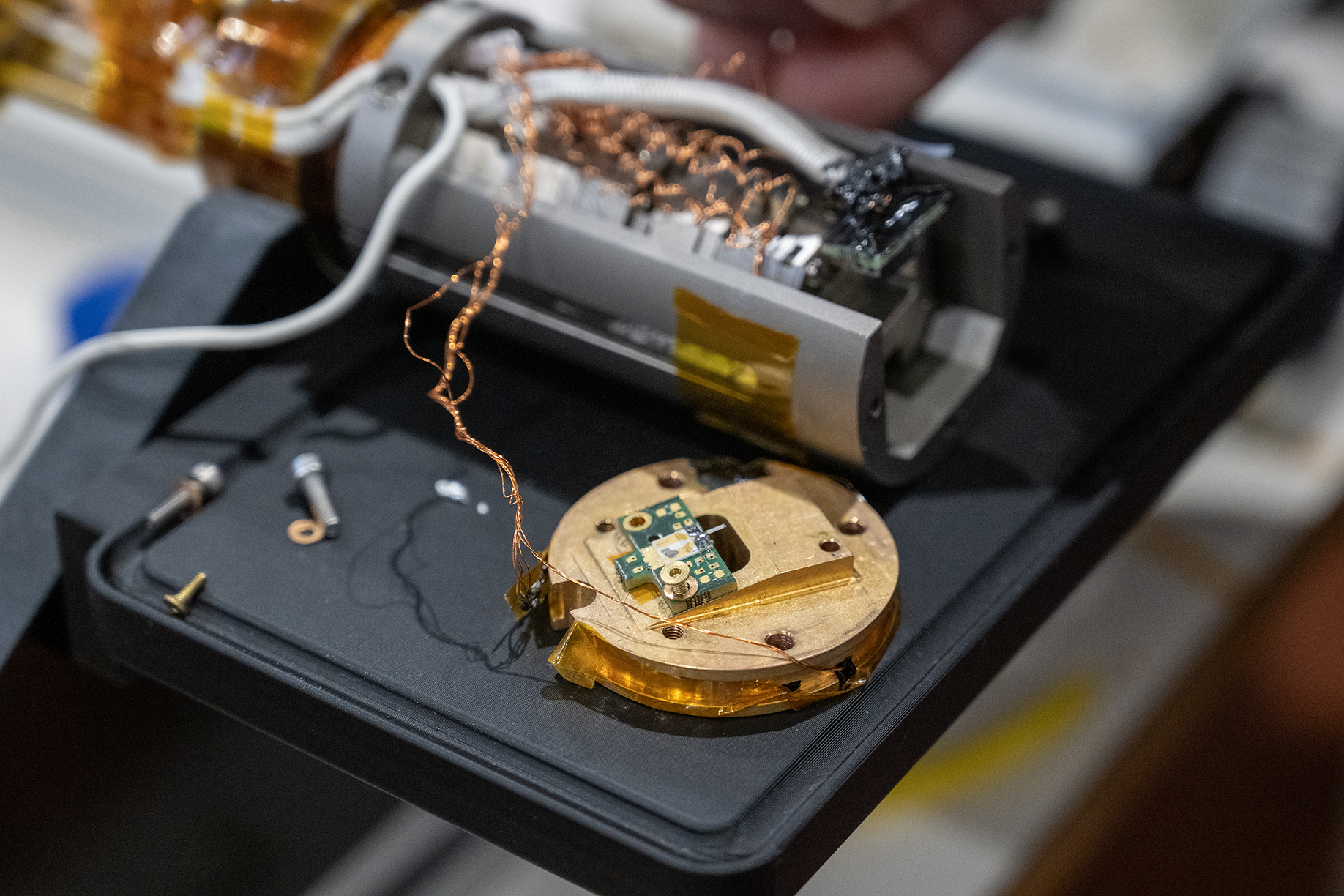

The microscope tip being hoisted above the cryostat where the measurements take place -

Measurement of a copper–cobalt heterostructure: the output is shown in four graphs -

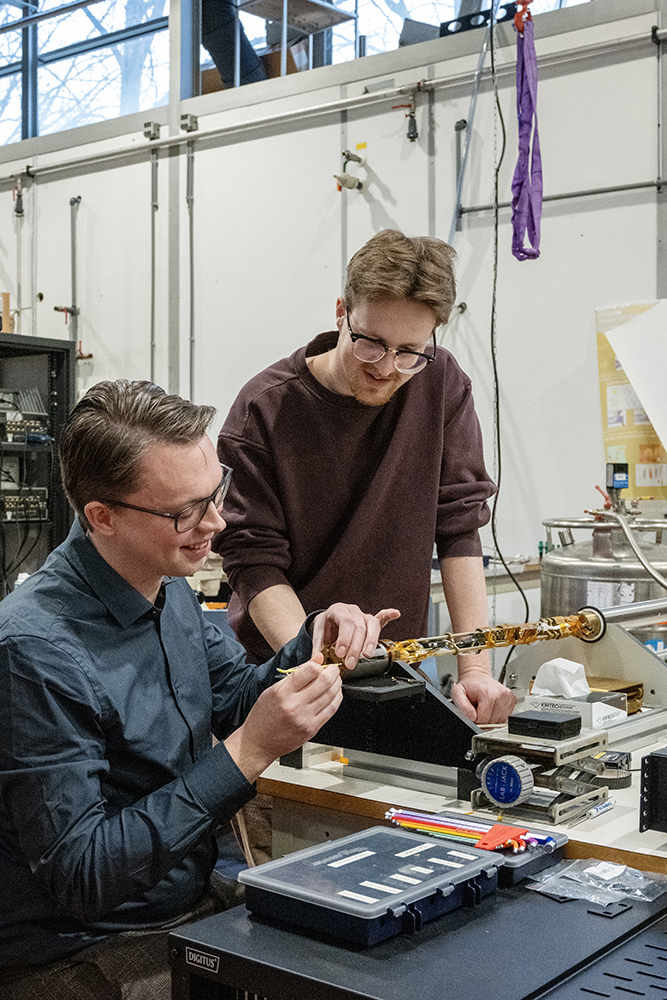

PhD candidates Matthijs Rog and Tycho Blom mounting the tip on the microscope -

Close-up of the installation of the microscope tip

Designed and built together with instrument makers

Since 2021, Rog and Lahabi have been working on the construction of this new microscope, affectionately nicknamed ‘Tortilla’ by the team. Its technical name is ‘Tapping Mode SQUID-on-Tip’ (TM-SOT). The build began with parts found in the attic of the university building, supplemented with a few commercial microscope components. It soon became clear, however, that their design requirements were so specific that they had no choice but to design and build almost every component themselves.

Rog and Lahabi enlisted the help of Christiaan Pen and Peter van Veldhuizen, colleagues from the Fine Mechanical Service and the Electronic Service. Together, they designed and manufactured every part of the microscope. ‘Every cable was soldered by us, and every screw was put in by hand,’ Rog says. ‘This project is a result of intense and fruitful collaboration between many different scientists, engineers and technicians. Microscopy experts from the group of Milan Allan and the talented engineers of QuantaMap all played a vital role.’

Start-up QuantaMap brings the microscope to market

The same microscope is now being developed as a product by QuantaMap – a company based at House of Quantum Leiden, co-founded by Lahabi. ‘We see strong potential in quantum diagnostics,’ explains CEO Johannes Jobst. ‘We concluded that one of the major road-blocks of quantum computing is that when chips do not work as well as they should (they often don’t), there is no way to find out which component failed. Nor how to improve the production process. Our novel microscope can solve this diagnostics challenge and help enable the quantum revolution.’

Read the paper in Nano Letters.

Tapping-Mode SQUID-on-Tip Microscopy with Proximity Josephson Junctions

Matthijs Rog, Tycho J. Blom, Daan B. Boltje, Jimi D. de Haan, Remko Fermin, Jiasen Niu, Yasmin C. Doedes, Milan P. Allan, Kaveh Lahabi