How Leiden researchers are going to fight Gaucher's disease with a start-up

It has kept Leiden professor Hans Aerts busy throughout his academic career: Gaucher's disease, a hereditary metabolic disease. Together with professors Hermen Overkleeft and Stan van Boeckel he developed promising compounds that can serve as medicines against this disease. The biotech-startup Azafaros, co-founded by the trio in 2018, raised 25 million euros for clinical trials at the beginning of this year. Aerts and Overkleeft tell how they outsmarted an American biotech company.

A better alternative

The new drug should become a more convenient and cheaper alternative to the current treatment of Gaucher's Disease, the administration of synthetic enzyme via an intravenous infusion. Moreover, the drug would also be beneficial for patients with complaints of the central nervous system; the administered enzyme does not cure these complaints. 'It's unique that scientific research has been brought to a company so quickly,' says professor of Bio-organic synthesis Overkleeft. Aerts, professor of Medical biochemistry, says: 'Gaucher's disease has occupied me throughout my career and I have always had the practical application of my fundamental research in mind. Now we have reached that point.'

Accumulation results in enlarged organs

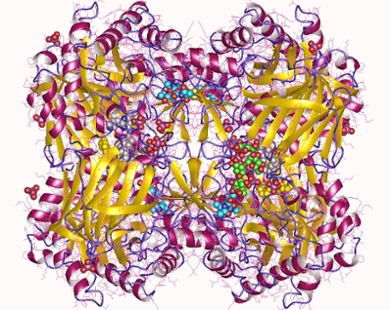

Gaucher's Disease is a so-called lysosomal stacking disease. It is caused by the accumulation of glucosylceramide. The substance - a sugar linked to a fat - is part of the cell membrane. The compound is continuously produced and converted into other fat compounds, or broken down. The breakdown takes place in special vesicles in cells, the so-called lysosomes, where the enzyme glucosylceramidase cuts the substance into two parts. People with Gaucher's Disease have an error in the gene coding for the breakdown enzyme; as a result, the enzyme does not function properly, so that the amount of glucosylceramide increases in the lysosomes. The condition is hereditary.

Glucosylceramide accumulates particularly in the lysosomes of certain white blood cells, the macrophages; they swell into so-called Gaucher cells. These cells accumulate in the spleen, liver or bone marrow, resulting in enlarged organs, a swollen abdomen, bone pain and poor blood clotting. In some variants, the central nervous system is also affected.

A miracle, but not big enough

For a long time, healing was not possible. In severe cases, doctors removed the spleen but then the liver often became greatly enlarged. Since the 1990s it has been possible to produce the breakdown enzyme synthetically, usually in genetically modified animal cells. Patients are administered that enzyme via an infusion. 'The result is spectacular: the abdominal circumference decreases, complaints disappear,' says Aerts. 'But the treatment is drastic and expensive. And a disadvantage is that the enzyme cannot cross the blood-brain barrier. So it doesn't help people with neurological complaints.'

A new approach

Aerts, an expert in the many enzymes involved in the metabolism of sugar-fat compounds such as glucosylceramide, devised an alternative approach. His idea was not to stimulate the breakdown of glucosylceramide in patients, but to inhibit its production so that the amount does not exceed what the defective breakdown enzyme can cope with. Reduced production is not a problem: people can cope with 10 per cent of what is normally produced.

The cunning trick of an American company

Enzymes are not only responsible for the breakdown of glucosylceramide, but also for the production. Overkleeft: 'These enzymes are called glucosylceramide synthases. We can reduce their activity with amino sugars that bind to them and inactivate them. Sugars have a ring of carbon atoms with one oxygen atom, in iminosugars that atom has been replaced by a nitrogen atom. Chemical tails on an iminosugar determine how strongly that sugar inhibits enzyme activity.' His area of expertise is making such compounds. 'As early as 1994, we had a substance that had the desired effect and we patented it. The company Macrozyme, our first spin-out, started working with it. But the company was bought by Genzyme, where the compound remained on the shelf. With hindsight not so strange, because Genzyme produces the breakdown enzyme, for which our approach is an alternative.'

New Leiden attempt is successful

Because Genzyme had the license on the compound, Aerts and Overkleeft could not continue with it. But they made a series of dozens of new compounds that differed enough from the original ones to apply for a new patent - and they were even more powerful. Azafaros, based at Leiden Bio Science Park, now has the license to use this 'library' of molecules to turn it into a medicine for Gaucher's Disease. 'In clinical trials, they are going to test effectiveness, safety and side effects. In addition, they will investigate whether these molecules cross the blood-brain barrier and how they can scale up production,' says Aerts. Overkleeft: 'A drug based on such a compound is easier and more reliable to make than an enzyme, it has a longer shelf life and is easier to store.

The name Azafaros comes from faros, Greek for lighthouse. The name refers to the famous lighthouse of Alexandria which in ancient times housed the largest library in the world. The prefix aza is synonymous with imino, a chemical name for the presence of a certain nitrogen group.

Fundamental research continues

The chemists can get on with their fundamental research. Glucosylceramide synthase also plays a role in the intestine and appears to be involved in type 2 diabetes. And there seems to be a mysterious link with Parkinson's Disease: of all Dutch people suffering from Parkinson's Disease, 38 per cent are carriers of a gene mutation that causes Gaucher's Disease. The researchers also want to apply their approach to other lysosomal accumulation diseases, such as Fabry disease and Pompe disease.

Text: Willy van Strien