‘The study of cuneiform texts is still an open field’

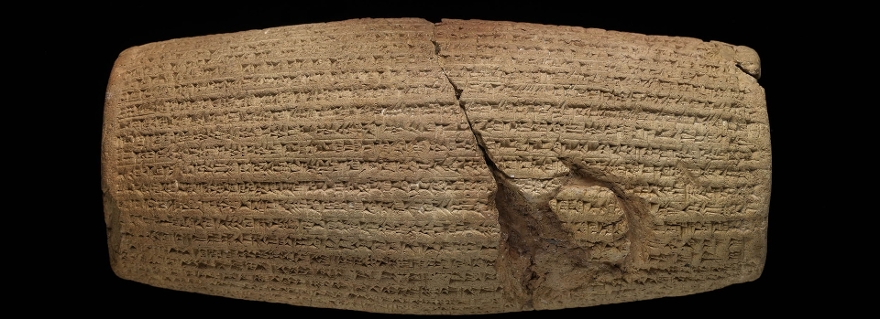

The oldest forms of literature and law originate from Mesopotamia (3000 BC until AD 70), as do important discoveries in science and technology. All these developments were recorded in cuneiform texts on clay tablets. There is still a lot to learn from the study of cuneiform texts, says Professor of Assyriology Caroline Waerzeggers. Inaugural lecture on 1 December.

Assyriologists are sometimes asked what the point is of studying cuneiform texts. However, Caroline Waerzeggers is positive about the study of this script from ancient Mesopotamia. An abundance of newly discovered clay tablets means that the blind spots in ancient history can be filled in. This is providing a wealth of important information, says Waerzeggers. ‘Mesopotamia is important in the history of humanity because of its chronological priority. For instance, in the field of state formation, literature, science and ideas about freedom and citizenship.’

Not just Europe is heir of Mesopotamia

Assyriologists must also draw more attention to the position of Mesopotamia in world history, says Waerzeggers. ‘Mesopotamia is often presented as a prelude to the European wonder: the flame of civilisation was first lit in “the Orient” and the Greeks then brought this to Europe. In this vision Mesopotamia belongs to “us”. But you exclude many groups of people, who are also the heirs of Mesopotamia. With our fixation on Greece and the biblical world, we systematically eradicate from the history books the complex effects in its own region and the cross-pollination with areas to the east of Mesopotamia, namely, Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia.’ This must change, says Waerzeggers. Mesopotamia has a greater relevance to the deep history of humanity, as a collective process, than we appreciate. ‘Even if we look at our own society in the Netherlands, Mesopotamia is a shared moment in the history of different groups in the population.’

Illegal excavation and trade

At the same time, Waerzeggers flags up a problem that assyriologists must address. Over the last 20 years, numerous clay tablets have ended up in the hands of collectors through illegal excavation and trade. Many assyriologists see it as their duty to collaborate with the owners and publish these texts. This causes a dilemma: does the study of such a clay tablet increase its market value, thus encouraging robbery? Or should assyriologists only worry about its historical value? Waerzeggers thinks that assyriologists should take it upon themselves to voice this dilemma instead of being called to account by outsiders. They should also debate among themselves when studying such a tablet is responsible.

The tablets that have already been found and documented must be looked at more critically. In which context were the texts written and how should we interpret them? ‘In short, an open field awaits us,’ is her optimistic conclusion about the future of Assyriology.

Why was Mesopotamia so important?

The territory of Mesopotamia lay largely in modern-day Iraq, but also covered part of present-day Syria, Turkey and Iran. The cuneiform script was used in this region between about 3000 BC and AD 70, and hundreds of thousands of clay tablets and inscriptions have been preserved. They give a good impression of political, societal and cultural developments during these three millennia. Alongside important discoveries in the field of science and technology, the oldest forms of literature, law and bookkeeping have been found in this region. When the Persians and subsequently Alexander the Great conquered the area (in 4 BC) this knowledge was transferred to ancient Greece and later to other European countries. Mesopotamia is thus considered the birthplace of Western culture. However, the developments in the Middle East itself and the contacts between Mesopotamia, Iran and Central Asia have not been studied as much.